(Julie Lonneman)

The first swimming pool I remember was a horse tank set in concrete in the small park across the street from our house on Circle Drive. Someone brought it in from the country so we would have a place to swim. The tank was made of corrugated tin, a big metal cylinder secured with rivets.

The first baptism I remember was my cousin's. Nine-year-old Carol Ann was baptized by full immersion, "dunked" in the Southern Baptist way. And not a single dunking, but three times: down under the water and up, down under the water and up, down under the water and up.

Even a child old and determined enough to "make a decision for Christ" dreaded the baptism, which looked and felt more like drowning than washing. So my cousin and her mother, my aunt, practiced for the big day in the horse tank. Carol Ann wore a nose clip and a bathing cap, though on the appointed day she would have to accept water up the nose and hair dripping water in her eyes. Her mother practiced dipping her backward, covering her mouth and nose with her hand, down into the water. Carol Ann would slap the water and struggle, then be brought up, spluttering and choking. They would practice until she could go down and come up smoothly, as though being held underwater by a large man with his hand over her mouth and nose was a matter not of terror, but of joy.

Childbirth would teach us both how the two emotions could, and do, meet in a single moment. But at the time, it seemed contrary to nature, and nature's God.

My Southern Baptist kin disdained the baptisms of those of us who had been "sprinkled," and at such an early stage of infancy that we had no memory of the water or the oil or the words. They felt strongly that we still needed to give a testimony, a sign of our own acceptance of the Gospel, independent, so they said, of our parents' and grandparents' choices. When we played church with the Richards children, who lived on the corner, Freddie Richards always preached, and he always included a long altar call. I remember a blind evangelist who preached a revival in Tulia. He reminded God, while we listened in, of the number of souls who had "heard the call," who wanted "to make sure their names were written in the Book of Life," but who had resisted, stubbornly keeping their seats. A fair number had perished on the way home, their cars wrapped around telephone poles or cut in two by freight trains. How could sprinkling defend against the foe?

And it was true that little in our lives could match the stern majesty of the red velvet, floor-to-ceiling drapes hanging behind the pulpit of the First Baptist Church in Tulia, Texas. The drapes covered the baptismal pool, with its waist-high glass separating the sea and the dry land. Behind the pool, a painted mural covered the wall. It was a scene, we were told, from the River Jordan. I think now it is a scene of the River Jordan if the River Jordan had been located in East Texas, where most of our families had settled before moving west in search of cheap, abundant land.

On the day of a baptism, the drapes would part — like the Red Sea, I thought, deeply moved — and we would see the preacher, dressed in robes, waiting for the candidate, who would come to him through the water.

I think of those people, whom I have loved and left and lost, every Lent, as the days grow close to Easter. I think of the catechumens, now the elect, who are practicing for their baptisms as surely as my cousin practiced for hers.

Advertisement

There was a wisdom I only later understood in those rehearsals. My cousin was being asked to undergo something contrary to instinct — indeed, to the strongest instinct, that of self-preservation. The first thing every would-be lifeguard learns is that people who think they are drowning will fight to stay afloat. They will even fight their rescuers, in the mistaken belief that the outstretched arms are there to push down to death rather than pull up to life.

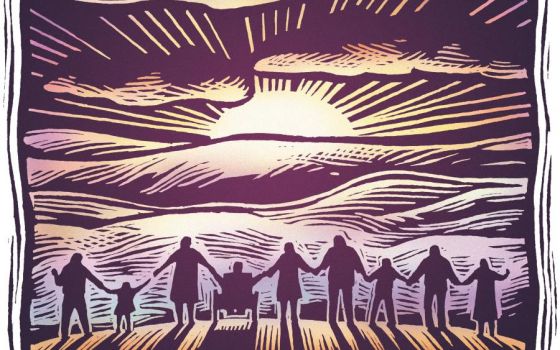

We are asked in baptism to put aside our selves and die to Christ, to put aside our individual life preservers and climb in the leaky ark with the rest of the world. It is contrary to instinct, and instinct is hard to overcome. It is hard not to slap the water, choking and spluttering and fighting all the way.

So the elect practice, as do we, the baptized. We, who have waded in these waters a long time, still must surrender to them each day, until what is terror is also joy.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2011 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.