An icon of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus at Mar Sarkis monastery in Maaloula, Syria (Wikimedia Commons/Iyad Al Ghafari)

Editor's note: An extended version of this essay first appeared at Political Theology Network's "Catholic Re-Visions" blog.

There is an unofficial canon of queer Catholic saints. Those who know it, know it. These are historical, canonical, Vatican-approved Catholic saints — saints that our grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and ancestors in faith have prayed to for centuries — that in the past 50 years or so have been unofficially but popularly labeled as "queer."

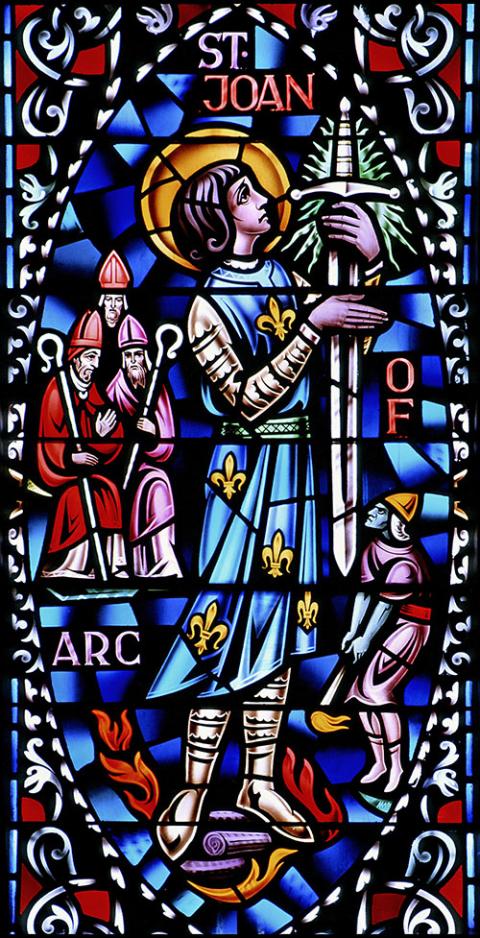

We can think of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, Roman soldiers and Christian martyrs in the late third century, venerated by queer Catholics as models of same-sex love in early Christianity. Or we can think of Sts. Perpetua and Felicity, second-century Egyptian women martyrs known for their deep love for one another. St. Joan of Arc's cross-dressing in male uniform, along with her martyrdom at the hands of the church, allowed many to venerate her as a trans or gender-nonconforming saint. The third-century martyr St. Sebastian is known as a symbol of male beauty and homoerotic desire.

The list goes on. Biblical passages telling the stories of close intimacy between Ruth and Naomi or David and Jonathan are often proclaimed at queer Christian weddings. Icons of Perpetua and Felicity by Br. Robert Lentz began appearing in queer circles and official Catholic stores alike since the 1990s, alluding to these and other saints' queerness without openly ever claiming so.

Iconography of queer ancestors such as Harvey Milk, Matthew Shepard, and Marsha P. Johnson, too, began to emerge, complexifying who we understand to be a saint and a spiritual ancestor.

Queer Catholicism, for many people who identify with it, involves a spiritual practice of grasping at traces of queerness in church history, of capturing vignettes of queer presence. We look to moments of same-sex friendship in Scripture and tradition as models for our own queerness as Christian love. We search for reasons to believe that queer people have always been there in the church throughout history.

Queer Catholicism demands a spiritual practice of bold imagination and history-searching despite what is recorded. Using bold imagination and persistence, we find ourselves in the otherness of the church's saints and at the heart of Christianity.

In other words, queer Catholicism relies on some form of invention in its story-telling and lineage-tracing. Our spirituality rests upon a recognition that we may never truly know if the queer saints are actually queer or not. Nevertheless, we continue to imagine a past (and a future) in which vestiges of our queer selves are present in the spiritual lineage of the church.

The term "invention" when used side by side with "history," often holds negative connotations. "Why invent queer Catholic saints, when it's easier to simply leave the church?" those outside the church may ask queer Catholics.

The same queer practices of invention are also chastised by Catholics who hold onto a heterosexist imagination. In their eyes, queer Catholics are just "making things up," or worse, merely creating scandal by suggesting the queerness of the saints.

"St. Sebastian," 15th-century painted terra cotta sculpture by Matteo Civitali at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (NCR photo/Teresa Malcolm)

Yet invention as praxis is not new — but maybe even central — to our Catholic spiritual practice regarding venerating the saints. Looking at Catholic history as a whole, we can see that many stories of the saints are also stories of inventions of the past. These hagiographies are invented not for the sake of falsity, but out of longing for a spiritual ancestor who shares in their faith and their struggles for survival.

We may never know how and whether St. Veronica's veil imprint of Christ's suffering face, St. Padre Pio's flying to preserve a war-torn city, St. Juan Diego's roses from Our Lady, and countless other stories of saints took place in history. Yet the church draws on these histories of our saints as strength to fuel our faith during times of upheaval, persecution, and struggle for identity.

To speak of saints as "invented" is not to say that these saints and their stories were not real, but rather, that retrieving the stories of our saints requires faith and imagination, rather than a mere recovery of historical facts.

For Catholic communities of color, a similar spiritual practice of invention is also needed when it comes to looking for saints who share our racial identity. Where are my Catholic ancestors? I asked this prior to my confirmation, after failing to find a Chinese woman confirmation saint who was not primarily known for her martyrial death or humble servitude.

Advertisement

Official narratives surrounding the saints of the Global South seem to rarely escape the exoticized colonial imaginary: Most Asian saints are martyrs at the hands of an anti-Christian state; many Indigenous saints are praised for their conversion, while the colonial violence surrounding Indigenous conversions are elided.

Sometimes, the traces of our presence in history risk becoming an essentializing presence. The few saints of color are treated as totalizing representation of their marginalized identities, leaving Catholics of color thirsting for something more, someone more.

For queer and marginalized Catholics, recovering traces of our presence from a predetermined archive is not enough. Rather, a different type of project beckons the queer, brown Christian: Invention, coupled with mourning for what is irrecoverably absent, becomes a necessary spiritual practice for all those who cannot find their own ancestors and saints in the canons of church history.

A mosaic of martyrs Sts. Perpetua and Felicity adorns a chapel wall in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

Every act of inventing the story of a queer saint, queer theories remind Catholics, comes with a sense of mourning for what is categorically absent or erased from canonical Catholic hagiography: mourning for ancestors who may not have ever been there, ancestors and holy people whose names we shall never know.

Through this dual act of mourning what is absent and inventing a new possibility of presence, the incomplete fragments of church history and its myriad possibilities come to haunt and disrupt all of us, demanding us to remain open to who our saints are and who our saints could be.

I return, at the end of my workday, to my home altar of queer saints, whose blank spaces in between all the queer-coded iconography bear witness to the many Catholic and non-Catholic ancestors I will never know. I light a small candle under the altar, not only in remembrance of Perpetua and Felicity, Sergius and Bacchus ... but also of all the generations of queer faithful who have instilled subtle yet subversive queer meanings onto the stories of these saints. I light a candle in remembrance of each queer seeker in history who prayed to the Litany of Saints, imagining and finding echoes of themselves in the silences between each invocation and each name.