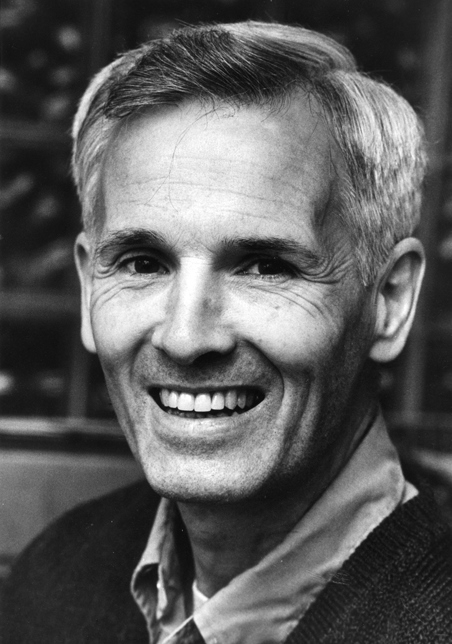

Terry Dosh (Courtesy of the Dosh family)

Terry Dosh, for more than 50 years a leader, organizer and member of U.S. Catholic reform groups that emerged after the Second Vatican Council, died at his home in St. Paul, Minn., April 7. He was 85.

Dosh, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 10 years ago, began hospice care late last year. He died surrounded by family and friends, and his wife of 44 years, Millie, was with him.

A former Benedictine monk, Dosh was the first coordinator of CORPUS, an association for former Catholic priests. Dosh said that his special concern was that priests who had married and left the institutional church should continue to play active roles in the church’s future.

Friends say Dosh had a prodigious knowledge of church history and he wielded it not like a sword, but as a penetrating spotlight to clarify issues and resolve entanglements among the groups to which he belonged.

“History was always on the tip of his tongue,” said Mary Lou Hartman, former president of the Association for the Rights of Catholics in the Church and a board member of FutureChurch. “He was a living encyclopedia of facts and dates.”

Paula Ruddy, a founder of the Catholic Coalition for Church Reform in Minneapolis, agreed. “I remember meeting Terry by chance in the grocery store one day,” she said. “We stood in the aisle for over a half hour talking. I think it may have been about the 14th century.”

Terence Dosh was the sixth of seven children born to Chuck and Lil Dosh of the Twin Cities. They were “tolerant” parents, he recalled in a short autobiography. “They were open to different races, colors and creeds, and all were welcome in our home.”

His early education was at schools operated by Benedictine monks, and he joined the order at age 19. After his ordination as a priest in 1957, he taught at St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minn., while earning a doctorate in early modern European history at the University of Minnesota. He later taught history for five years at California State College in Dominguez Hills.

Deeply influenced by Vatican II (1962-65) and what he called the “tumultuous” cultural climate of the priesthood after the council, he left the Benedictines in 1971 and married Millicent Adams.

“I came to believe that I was to be a player in that prophetic cataclysm known as the great exodus of priests,” he wrote.

Millie, who had been a member of a Poor Clare community and was later a Montessori teacher, commented on the wonderful travel opportunities she and Terry had in connection with his work during their 44 years of marriage. “We went to Europe 10 or more times,” she said, along with countries such as Ecuador and Mexico.

Millie also commented on the fantastic education in church history she gained just by living with Terry and seeing him in operation.

“Terry Dosh never left the priesthood he was called to by his church,” said Fr. Kevin Clinton, a priest of the St. Paul-Minneapolis archdiocese and a longtime friend of the Doshes. “He did leave the mandated, celibate, clerical box that has trapped the humanity of so many priests. ... He used his priesthood, organizational ability, marriage and family life to advance the movement of God’s Spirit flowing from the council.”

Terry Dosh is survived by his wife; their two sons, Martin Luther King Chavez Dosh and Paul Gandhi Joseph Dosh and their wives; four grandchildren; and his brother Fr. Mark Dosh.

Memorial and funeral services are scheduled at St. Frances Cabrini Church in Minneapolis. On April 15, there will be visitation at 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m., followed by vespers at 6:30 p.m. The funeral Mass will be Saturday, April 16, at 10:30 a.m., followed by lunch and a program.

Even before departing the institutional priesthood, Dosh had been an active member of the organization now known as the Federation of Christian Ministries,* holding several leadership roles and organizing two national conferences.

In 1984, he joined the growing organization called CORPUS (Corps of Resigned Priests United for Service). Frank Bonnike and the two other co-founders of CORPUS asked Dosh become the first executive secretary for the group.

“Terry was perfect for the job,” said Bonnike. “He was both a people person and a scholar. He kept up on the church. He had this high level of energy. He was simply invaluable.”

For six years, Dosh was constantly in motion, visiting some 100 cities, meeting with disparate groups of resigned priests, bringing them into the national fold of CORPUS, forming networks with area representatives of the body and editing CORPUS Reports.

Meanwhile, the married priesthood phenomenon had become international, and CORPUS played a leading role in getting the various groups to collaborate. In 1985, Dosh and other members attended the first international meeting of married priests in Ariccia, Italy, near the pope’s summer residence.

He also helped create the International Federation of Married Priests, serving as a board member and attending the federation’s first meeting in Paris. In 1990, after a stressful reorganization of CORPUS, Dosh resigned.

“Terry put CORPUS on the map,” said John Williams, a retired professor at the University of Wisconsin-Stout and longtime friend of Dosh. “He ramped up the membership. You know, he wasn’t just a talking historian; he was a practicing, doing historian. And I think his approach gave hope to a lot of people, kept them in the church.”

Bill Hunt, a former director of the Newman Center at the University of Minnesota, cited Dosh’s piercing mind. “He was a voracious reader, especially in church history, yet there was no arrogance or ostentation about him,” Hunt said. “There’s a kind of liberating quality when you really understand what’s gone on in the past. It wards off despair. Terry had a fierce loyalty to the church because he knew so much about it.”

Dosh served for some 20 years on the board of the Association for the Rights of Catholics in the Church. Hartman, the group’s former president, commented on his warmth and spirituality. “I think a lot of that goes back to his time with the Benedictines. He never lost that charism of the monk. He kept the Benedictine heritage and lived it in every job he ever had.”

One of his less formal jobs was as an independent, itinerate religious educator in the 1970s and ’80s. He provided adult education talks and courses in dozens of parishes, covering Catholic, Protestant and Jewish issues.

Throughout his career, Dosh invariably wore his bright green trousers to any event where the public was invited. He called them his “Resurrection pants,” a sign of hope and an easy way people could identify him in a crowd.

In 1991, Dosh founded Bread Rising: A Report from Terry Dosh, a four-page newsletter on church renewal, which had more than 1,000 subscribers at the time of his death. With the help of Millie in later years, he presented quotes from the British Tablet, National Catholic Reporter and other publications, other bits of news about the church, and brief notes called “Signs of Hope,” which reflected his own irrepressible hope for the church.

Dosh said that the election of Pope Francis in 2013 had bolstered that hope. “He is a pastoral pope,” Dosh said, “and that is rare. He acts in a collegial manner, and it’s clear that poor people have changed him.”

Dosh was especially encouraged by Francis’ directive that papal nuncios should submit for consideration as bishops the names of priests who are pastoral and close to the people.

In 2008, he was a founding board member of the Catholic Coalition for Church Reform, an activist progressive organization in the Twin Cities. Ruddy said Dosh was “unstintingly and unfailingly helpful” in guiding the organization, although illness forced him to leave the board in 2010.

The group has sponsored several synods of the baptized and drew the attention of now-resigned Archbishop John Nienstedt.

“We included a sentence of Terry’s on our website,” Ruddy said, “and it was the only sentence the archbishop singled out as ‘false’ and ‘inflammatory’ ” in a letter Nienstedt sent to her in 2009. The sentence was, “Mandatory celibacy is quintessentially anti-woman.” But, noted Ruddy, “isn’t it a great sentence to be condemned for?”

Since 2006, Dosh had battled Parkinson’s disease. At first, it affected his voice, gradually crippling his ability to talk, swallow and walk. But he continued swimming, maintained his lifelong reputation as a ravenous reader, and kept up a weekly telephone conversation with his old friend John Dubay, another married priest, until the fall of 2013.

“I know he hates to leave,” Dubay said. “He poured his heart and soul into the church. He loved it and he never gave up on this idea of those who had left the clerical priesthood having a role on the periphery and challenging the center.”

*An earlier version of this story included an outdated title for the Federation of Christian Ministries.