Pope Francis greets a family as they present offertory gifts during a Mass marking the feast of Mary, Mother of God, in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Jan. 1, 2017. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The controversy surrounding Amoris Laetitia ("The Joy of Love") began even before the document was issued, even before the two synods that discussed the issues surrounding marriage and the family, discussions that served as the basis for Amoris Laetitia.

On Feb. 20, 2014, Pope Francis invited Cardinal Walter Kasper to address the cardinals gathered for the first consistory of the new pontificate. Kasper's book Mercy had profoundly impacted Francis and he asked the German cardinal to share his insights with the other cardinals. Among the items Kasper discussed was his conviction that the church needed to revisit its pastoral practice in regard to those Catholics who had divorced and remarried.

Cardinal Walter Kasper arrives for the concluding session of the extraordinary Synod of Bishops on the family at the Vatican Oct. 18, 2014. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Conservatives hit back quickly, publishing a book, Remaining in the Truth of Christ, that challenged Kasper's proposal and included essays by such prominent churchmen as Cardinals Walter Brandmüller, Raymond Burke and Carlo Caffarra. The various essays all struck a common theme: The church's teaching on marriage is "irreformable," based on the words of Jesus in the Gospels, and unchanged for two millennia of Christian life.

Of course, the church's pastoral practice on marriage has changed repeatedly over the centuries and whether or not the teaching is "irreformable" was to be a subject for the synods.

In the fall of 2014, the first of the twin synods was held and Burke was again prominent among those voicing his concerns, claiming the discussions and press coverage were being manipulated. The discussions within the synod hall were not public, but it was clear that a majority and minority party had emerged, with the majority open to the Kasper proposal.

In voting on the final report from the synod, most propositions garnered nearly unanimous support but three paragraphs regarding LGBT outreach and the issue of how to help divorced and remarried Catholics failed to garner two-thirds of the voting prelates, although they did attain a majority.

The following year, in fall 2015, a second synod was held and controversy started again before the meetings began, with charges that the process was being manipulated. During the discussions, the two camps again faced off, but this time all the paragraphs in the final document cleared the two-thirds majority, including those pertaining to a possible opening for the divorced and remarried to return to the sacraments.

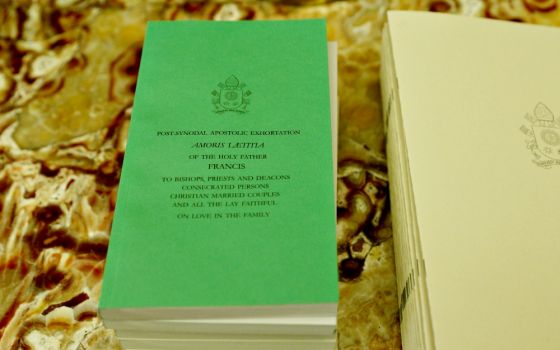

Francis issued Amoris Laetitia in April 2016. He drew heavily on the documents issued by the two synods, as well as other traditional texts, such as the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas and the decrees of the Second Vatican Council. Most of the document was non-controversial but, following on the recommendation of the synod fathers, Francis opened the possibility that those who are divorced and remarried might, through a process of discernment with their pastor, return to the sacraments, that is, the Kasper proposal.

In November 2016, Brandmüller, Burke and Caffarra, all of whom had contributed to the book opposing the Kasper proposal, joined by Cardinal Joachim Meisner, archbishop emeritus of Cologne, Germany, took the extraordinary step of publishing five dubia, or doubts, that they had regarding Amoris Laetitia.

Cardinal Raymond Burke leaves the morning session of the extraordinary Synod of Bishops on the family at the Vatican Oct. 7, 2014. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Typically, a bishop with a question about a particular theological point will submit a dubia to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, seeking clarification. The four cardinals chose to publicize their letter when they received no reply, turning the dubia process from one of good-faith questioning into an open challenge to the pope.

The dubia asked if the church still teaches that there are certain acts that can never be done, whether the prohibition against receiving Communion still applied to the divorced and remarried, and what the role of conscience is in moral decision-making for a Catholic. All the questions sought to pit a particular, and very conservative, interpretation of previous magisterial statements against statements contained in Amoris Laetitia.

Burke has frequently made himself available to the media to amplify his concerns, for example appearing on EWTN several times for lengthy interviews. Since the publication of the dubia, two of the four cardinals — Meisner and Caffarra — have died.

The range of episcopal responses to Amoris Laetitia varied considerably. In Philadelphia, Archbishop Charles Chaput issued guidelines for the implementation of the document that could have been written before Amoris was issued, actually before the synods met. Nothing had changed in his view and so nothing will change in his archdiocese.

Conversely, the bishops of Malta issued guidelines that clearly indicated the divorced and remarried can, after a profound examination of conscience and in certain circumstances, return to the sacraments. The pope commended a group of Argentine bishops for their guidelines, which were similar to those from the Maltese bishops.

Advertisement

Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego convened a diocesan synod to discuss the issues raised by Amoris Laetitia.

The latest attack on Amoris Laetitia came in the form of a "filial correction" signed by several dozen professors and former professors, priests and others, most of whom had ties to the community of Catholics devoted to the traditional Latin Mass. The document accused the pope of spreading heresies and criticized him not only for Amoris Laetitia but also for the largely positive comments he made about Martin Luther on the anniversary of the Reformation.

[Michael Sean Winters is a columnist for NCR. Read his columns at NCRonline.org/columns/distinctly-catholic.]