RAISED BY THE CHURCH: GROWING UP IN NEW YORK CITY’S CATHOLIC ORPHANAGES

By Edward Rohs and Judith Estrine

Fordham University Press, $19.95

In the opening chapter of his memoir, Edward Rohs acknowledges that orphan life is largely seen through the prism of Hollywood -- think the Hollywood version of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Rohs promises the real story of growing up as a baby boomer orphan, one of the last in New York City’s Catholic institutions.

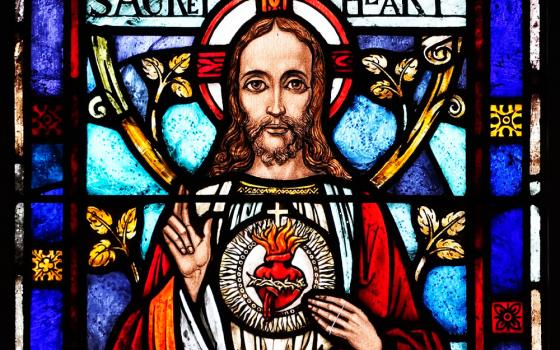

Some of that life was good, much of it routine, and occasionally it was brutal and horrible. What the reader comes away with is that Rohs, despite some happy memories, grew up disconnected with his world. He aged out of one orphanage into another Ñ all under the rubric of a holy mother church both maternally loving and a stern taskmaster of the Dickensian sort.

Born in 1946, Rohs was the child of a vagabond father and a frightened young mother, who dropped a 6-month-old infant off at an orphanage and never returned.

His first memories are of a Sisters of Mercy facility in Brooklyn where the nuns were frequently lavish in their care and attention. There he encounters a pleasant woman visitor who became an unofficial aunt. She took him home for holidays and special occasions.

Rohs describes how institutionalized life defined him. He recalls a brief experience with a foster family on Long Island. He found the routine of normal family life painful. “How can I tell them that I am frightened and lonely, and that the privacy they are giving me is creepy?” he writes, recalling his childhood dilemma.

Rohs’ tale is also that of New York City in his growing up years. He describes life in shifting city neighborhoods, as street gangs terrorized the orphan boys in what is now highly gentrified Brooklyn, and the wonders of life on the beach in Rockaway, Queens.

By the mid-1960s, the world of institutional orphanhood gradually took another tack, shifting to small group homes and foster care models. Rohs aged out of the system but returned as a care worker and then went on to a career as an athletic trainer at New York’s Fordham University.

During his orphanage years, he was twice sexually abused: by a visiting religious brother and by a lay worker. He recounts both in matter-of-fact detail. He handled the assaults and the growing sense of isolation they inflicted through prayer.

The book works best when Rohs dares to describe his personal orphan experience. It moves slowly when he describes the history of New York orphan care or his life outside the system. Some passages sizzle; others limp along.

Rohs’ orphan experience may have been Dickensian, or worse; yet much of it was spent in a warm family life, even if that family lived within the gray confines of Catholic institutional life. He has stripped away any Hollywood-inspired nostalgia.

[Peter Feuerherd is director of communications for the diocese of Camden, N.J.]