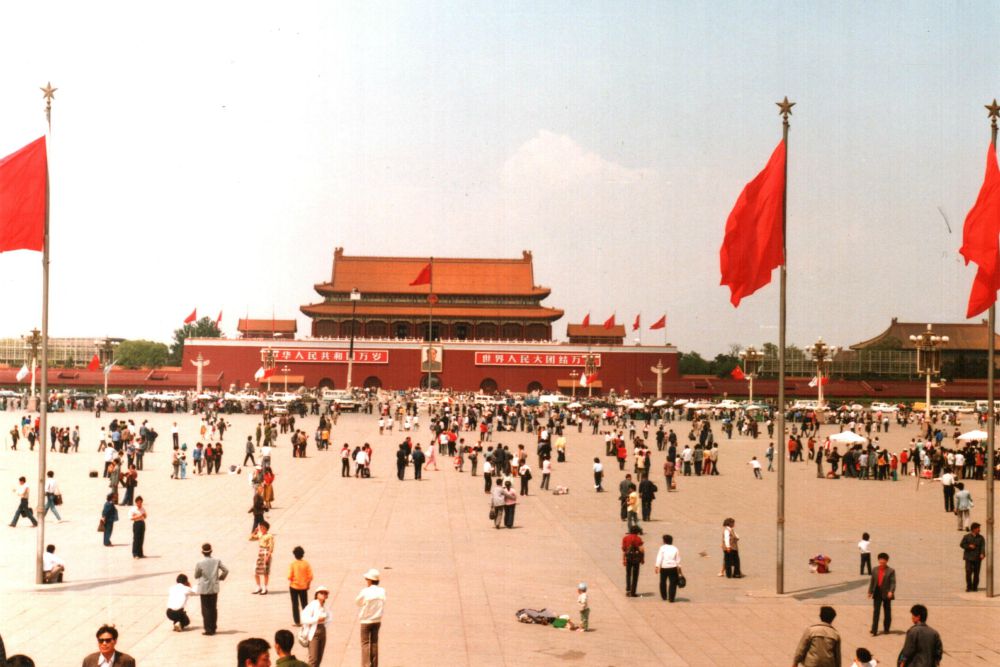

Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China, May 1988 (Wikimedia Commons/Derzsi Elekes Andor)

On June 4, 1989, at approximately 1 a.m., Chinese government troops began firing on the protesters at Tiananmen Square. No one is sure of the number of demonstrators present. Nor is anyone sure about the number of civilians who were killed, but the estimates range into the thousands.

Anna Wang, who was employed by the Japanese firm Canon, lived with her grandmother in Beijing at the time. Having recently graduated from college, she was not in the square during the violence, and her family members escaped the worst of what is now called the Tiananmen Square Massacre. But, like most Chinese citizens, they were psychologically wounded by the experience.

Wang's memoir, Inconvenient Memories, is her ninth book and first written in English. The narrative discusses the political and economic circumstances of China in the late 1980s and shows what led to the student demonstrations. It also covers the ways these events affected her life and her family's and friends' lives, as well as the fortunes of the Chinese people.

The central action concerns Wang's relationship with her grandmother who raised her; her parents lived in another city and were not able to arrange day care. Wang captures her grandmother's independent nature and some of her life story. She paints all with a fine brush, which notes both significant and inconsequential details.

The details add human interest to the story while also making it somewhat unwieldy. It doesn't help that that there are typos in the text every few pages. Since English is Wang's second language, these mistakes are forgivable. But one wonders why her editors didn't do a more careful job.

The memoir's final line, "God bless each and every one of you, especially China," repeats a quote noted a few chapters earlier from 17-year-old Michael Chang. Chang, an American-born Taiwanese tennis player, was the youngest person to win the French Open on June 11, 1989. The words, Wang says, brought her a glimmer of hope, making her feel as though she were still connected to human values in spite of the tyrannical machinations of her government.

Some of the most resonant writing here concerns Wang's falling out with her beloved grandmother over photographs that she had taken of the protesters. Wang had intended to publish them as a book.

Her grandmother, wanting to protect the fledging photographer, destroyed the pictures. As a result, Wang left her grandmother's apartment and, a few years later, left the country without saying goodbye. She, as did many Chinese people, became what she calls a perpetual immigrant.

As the memoir ends, Wang thinks about her grandmother, who has recently died and with whom she will never be able to reconcile. Feeling depressed, she says that she and members of her generation will never fully recover from the horror of a time when the Chinese government slaughtered its own citizens. This deeply felt memoir attests to those horrors.

First published by Granta Books in Great Britain, this book was titled The Cow Book. Its U.S. publishers changed the title to The Farmer's Son: Calving Season on a Family Farm. Both titles attempt to capture themes running through the book: cows, farming and the father-son relationship.

The original title suggests the extensive attention that Connell gives to the subject of cows, but it ignores Connell's personal problems and his difficult connection with his father. The second title doesn't quite work either, but it comes closer to the heart of the book.

Twenty-nine-year-old John Connell, who had left the family farm in Ireland several years ago, is back. He had experienced severe depression that he poetically describes as coming upon him "like a weighted cloak of water, pouring over body and soul until I felt that I was drowning."

Now, he must try to find himself and work out his emotional troubles while ostensibly helping his parents who — particularly in the case of his father — seem to resent their son's homecoming.

John Connell (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/Eamonn Doyle)

As he helps during calving season, he writes this debut memoir, which spans about six months. Written anecdotally as a collection of vignettes, it includes his musings on what it means to be a farmer, the history of farming and farm animals as well as their relationship with people, and bovine history and prehistory. It also concerns events from the present and the past — the death of an elderly neighbor, Connell's boyhood adventures, the history of the Irish people with their mix of Christian and pagan spirituality, and how these events have shaped him and his feelings.

As a boy, Connell wanted to be a priest and now is close friends with his 70-year-old pastor, Father Sean, who encourages Connell to continue with his writing. Connell attends Mass regularly and is concerned that religion is considered "a laughable word in modern life." He says that he has had his share of disagreements with the church, has doubted its teachings, and even "turned my heart from God."

But Connell doesn't tell readers what his doubts were and what effect they had on him. He also says little about his past emotional troubles. Moreover, the major subject, Connell's dicey relationship with his father, gets short shrift.

Connell's father has lost his parents as well as several close family members. He doesn't seem to have recovered emotionally, especially from the untimely deaths of two of his brothers. He has stopped praying and going to Mass and shuns religion. He seems vexed that one of his children has returned to the nest, especially since his youngest child is also still at home.

The tension between the two men is tight as a violin string. In one brief but electrifying section, they nearly come to blows. Afterward, they seem to reconcile, but as this somewhat disappointing book ends, it's anybody's guess whether or not they do.

Advertisement

Although all three sisters were close to their mother, Claudia Hernández had an almost visceral love for her. Hernández tells the sometimes rocky story of that love in her debut memoir, Knitting the Fog.

Told with the innocence and openness of a child's voice, the story revolves around the family migrating illegally to the United States. The book begins when Hernández is 4 and ends when she is 13.

The narrative, whose style is reminiscent of James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, offers vivid descriptions of places and people. It includes her memories of her father's alcoholism and her family's dysfunction, especially her mother's anger and the depression experienced by her oldest sister when she at 18 was forced to leave Guatemala.

As Hernández describes it, as a little girl, she would jump up on her mother and cling to her like a monkey. She wanted to sleep next to her and seemed to crave her presence. So when her mother decided to travel from her home in Guatemala and enter the United States illegally, her decision — although difficult for all three of her daughters — was especially hard on her youngest, Claudia.

Coming from a Roman Catholic family, Hernández remembers making her first confession and feeling lucky when she didn't have to report her transgressions in detail because of the long lines at the confessional. Interestingly, in this memoir, she does describe those failings — mostly having to do with sexual curiosity — that occurred in her early childhood.

She wonders about everything concerning her mother from what her naked body looks like and why she covers her private parts when she is bathing to why she has such a violent temper. She thinks about the mysteries of her mother's childhood and asks questions like: Why did Victoria grow up living in poverty with her Aunt Soila in Mayuelas, Guatemala, when she could have lived with her own mother in Tactic, a fairly prosperous nearby town with her new husband? Why did her mother only have a second-grade education when she was bright? Why did her mother never cry except in anger?

Set in Guatemala and the United States, the action includes Hernández's early childhood when she lived with her mother and alcoholic father, her elementary school days living with her aunt and her grandmother while her mother lived in Los Angeles for three years, her coming to the U.S. illegally with her mother and sisters, her middle school years in Los Angeles, and her visit in Guatemala with her grandmother and aunt.

A collection of poems and poetically written essays, much of the book first appeared in literary journals and anthologies. The chapters are arranged in chronological order, giving the collection a narrative structure that makes the story easier to follow, since Hernández intersperses poems among the essays.

The poems (written in Spanish and English) encapsulate the emotions generated in the surrounding essays. Some tend to be too abstract and difficult to understand, but they're filled with finely crafted details and figurative language that draw the reader into this subtly evocative memoir.

[Diane Scharper teaches memoir and poetry for the Johns Hopkins University's Osher Program. She is the author or editor of seven books including Reading Lips and Other Ways to Overcome a Disability, winners of the Helen Keller Memoir project.]