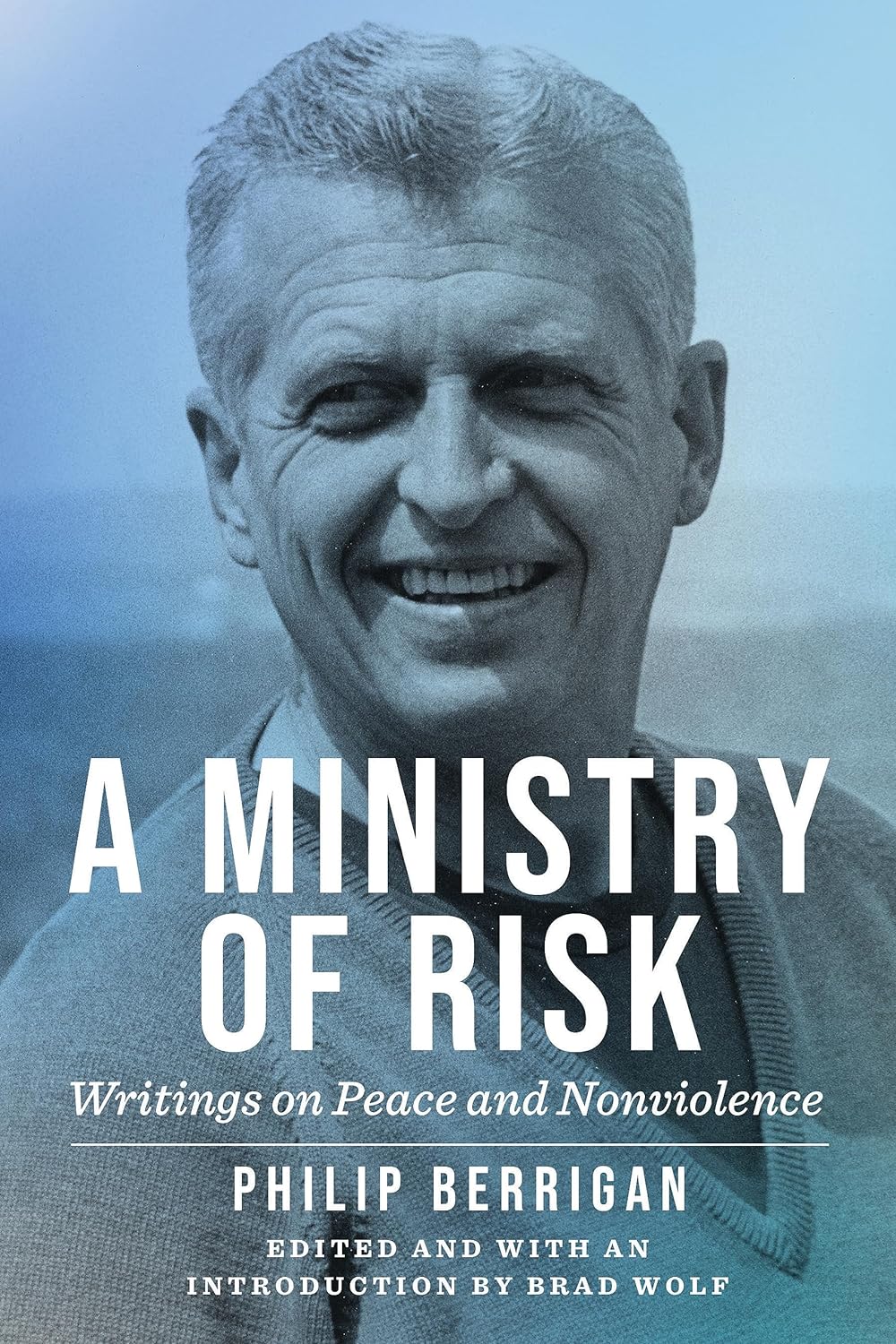

Peace activist Philip Berrigan is pictured at the University of Washington in Seattle in the summer of 1977. In "A Ministry of Risk: Writings on Peace and Nonviolence," Brad Wolf has compiled writings of the late Catholic war resister, who died in 2002 at age 79. (CNS file photo/Tom Salyer)

More than two decades after his death at age 79, the depth of the life of Catholic war resister Philip Francis Berrigan is presented in a collection of his writings, letters and speeches meticulously compiled by Brad Wolf, titled A Ministry of Risk: Writings on Peace and Nonviolence.

This collection, which chronicles 44 years of Berrigan's work, strongly makes the case that Berrigan — who spent more than 11 years in jail and prison for nonviolent direct action in opposition to war and nuclear weapons – deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Martin Luther King Jr., Mohandas Gandhi, Dorothy Day and scores of other 20th century prophets who risked life and limb to stop racism, global war-making and British and U.S. imperialism.

A World War II combat veteran, Berrigan reflected on his decision to join the war effort in his 2018 autobiography, Fighting the Lamb's War. In an excerpt from Wolf's prologue, Berrigan wrote: "I wanted to join the hunt for Adolf Hitler, to hack him into pieces, and to count the demons as they flew out of his wounds."

A revered peacemaker, Berrigan was also a fine warrior. In his biography Berrigan said he became "an expert marksman with a .37-millimeter antitank gun."

"I was a highly skilled young killer," he wrote, going so far as to compare his motives to those of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi war criminal, in that "we were both true believers, one a mass murderer, the other a killer on a smaller scale."

The collection's first entry is a July 27,1958, speech Berrigan delivered to an audience of teens. "Everything you do in life, the simplest and tiniest conscious acts, have something to do with whether you save your soul or not," he said. "What's it going to be with you?"

"What's it going to be with you?" was a question Berrigan asked again and again to those who would listen. While Berrigan's following was far smaller than King's and Gandhi's, his call to abolish war and for the creation of a more just, warless and better world for all humanity still rings true today.

A pickup truck carrying the casket of peace activist Philip Berrigan drives down a west Baltimore street during his funeral procession Dec. 9, 2002, three days after he died of cancer. (CNS/Martin Lueders)

As a young priest, Berrigan rose to prominence in Washington, D.C., Baltimore and New Orleans for his outspoken criticism of American racism. When the Vietnam War reared its ugly head, Berrigan — along with his brother, Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister, Sacred Heart sister who became his spouse — expanded his justice efforts to become the Catholic Church's most esteemed and hated opponent of the war that claimed millions of lives.

Early on, Berrigan's body of work closely mirrored that of King, his contemporary whose faith-based activism against racism and the Vietnam War was also prophetic and unwavering.

Wolf's collection makes frequent references to Berrigan speaking out against "capitalism, racism and militarism," the same tact King took in a speech delivered on Aug. 31, 1967, in which he identifies "the three evils of society," which he names "the giant triplets of racism, economic exploitation and militarism."

Almost five years earlier, in 1962, Berrigan wrote: "It wasn't difficult to make the connections between racism, poverty and militarism. I concluded that war is the overarching evil in this country."

Still on the theme of war in 1965, Berrigan writes, "War is obsolete, or humanity is." This quote is in the same vein of King's later, better-known quote: "It is either nonviolence or non-existence."

But it was Berrigan's call for "serious resistance" to the Vietnam War that set him apart as a unique nonviolent activist who clearly influenced the way millions of Catholics and other people of faith perceived the "Indochina" war, as Berrigan called it.

'It wasn't difficult to make the connections between racism, poverty and militarism. I concluded that war is the overarching evil in this country.'

—Philip Berrigan

In his introduction, Wolf writes: "Charismatic, brave, and scholarly, Phil was as well-read as he was impatient. He embodied the idea that the cup of salvation is caffeinated."

Berrigan's 1967 brainstorm to destroy draft files at Selective Service offices was a game changer in the U.S. antiwar movement, which was by then expanding exponentially as the war dragged on. The draft board raids upped the ante for antiwar activists and the government, landing the Berrigan brothers on the cover of Time magazine in 1971.

On Oct. 27, 1967, Phil, along with friends David Eberhardt, James Mengel and Tom Lewis, made international headlines when they entered a Selective Service office in Baltimore and poured blood on the draft files of men slated for military induction.

Known as "The Baltimore Four," they awaited arrest, were charged with felonies and jailed and ultimately found guilty and sentenced to federal prison.

After being released pretrial on bail, Berrigan immediately started planning a second, more spectacular raid at the Selective Service office in Catonsville, Maryland.

In his introduction, Wolf wrote: "Dan (Berrigan) was ambivalent about Phil's plan, but after lengthy discussions Phil convinced him that given the war's immense devastation, destroying draft records was morally and spiritually a justifiable means to save lives."

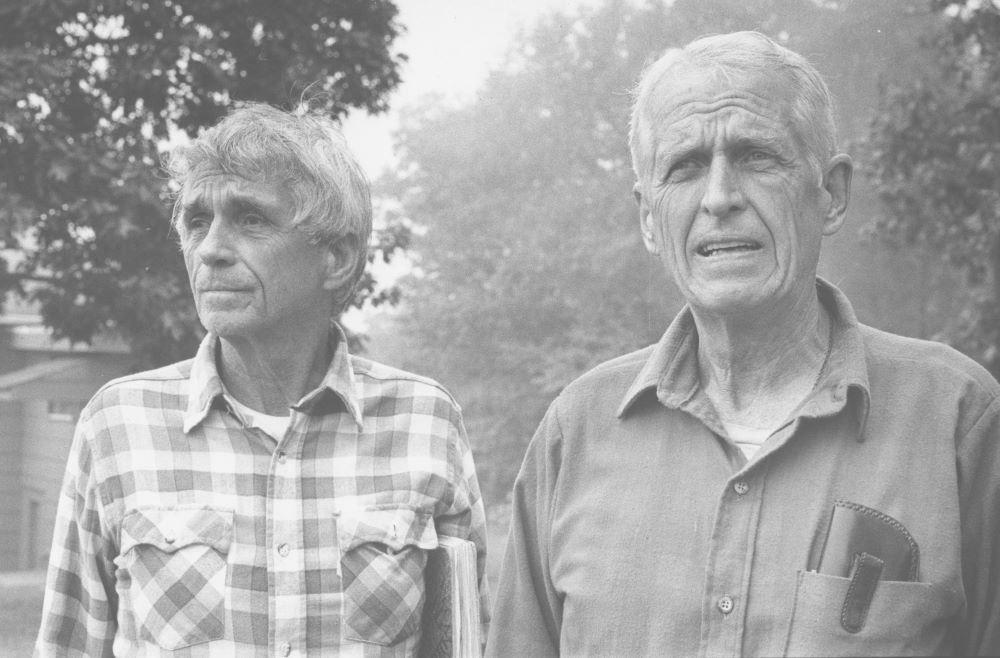

Philip Berrigan, right, and his brother, Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, lead a peace conference at Kirkridge Retreat Center, Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, in 1985. Philip Berrigan died in 2002; Daniel Berrigan died in 2016. (NCR photo/Walter Walden)

With his brother and seven others, on May 17, 1968, the group, known as "The Catonsville Nine" "struck again," Berrigan wrote. "[T]his time at a draft board in Catonsville, Maryland, where we carried hundreds of draft records into the parking lot and doused them with homemade napalm — soap chips and gasoline from a recipe we found in a Green Beret handbook."

The message of the nine, quoted in Wolf's collection, was famously articulated by Daniel Berrigan: "Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”

The nine, who notified the media before the raid, awaited arrest, went to jail, were found guilty of destroying government property and sentenced to federal prison.

Regarding the decision to burn the files, Phil Berrigan wrote: "We just wanted the judge and jury to see that our government was dousing Vietnamese children with the same terrible stuff we poured over those draft files."

Charismatic, brave, and scholarly, Phil was as well-read as he was impatient. He embodied the idea that the cup of salvation is caffeinated.

Eventually, Berrigan, who was unbowed by the consequences, received a combined sentence of six years for both draft board actions.

"Compared to the suffering of the Vietnamese, a few years in prison seemed a very small price to pay," Berrigan wrote.

One person who wanted to stop and neutralize the Berrigans was FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Using a prison informant, who copied letters Berrigan wrote from prison and turned them over to the FBI, led to another criminal case against Berrigan, McAlister and five others. The missives included love letters between Berrigan and McAlister, and others made obscure references to another plan for an action against the war that would include kidnapping and sabotage, charges Berrigan denied.

The 1972 trial of The Harrisburg Seven became big news. However, the government's case was weak, and the trial ended with a hung jury; the charges were eventually dropped. Berrigan and McAlister were convicted of a misdemeanor charge for exchanging smuggled letters.

"In Christ our Lord, word and deed were one – one life," Berrigan wrote on Feb. 21, 1972, in his opening statement for the Harrisburg trial. "[Jesus] never said anything that He didn't do."

In his 1973 book, Widen the Prison Gates, Berrigan wrote of his love and admiration for McAlister: "She is a striking woman, spiritually and physically. I have no illusions about her, nor she about me. We have experienced too much pain alone and together for that. Like the official horrors we face and resist, our relationship is a fact, and we are fully confident in it."

In his later years of activism, Berrigan kept his mind intensely focused on the extreme immorality of nuclear weapons and called for their abolition. Throughout Wolf's book, Berrigan's doomsday laments and calls for resistance to weapons of mass destruction remain steady.

In 1980, Berrigan came up with a new, more radical plan to oppose nuclear weapons, the Plowshares Movement, which takes its name from Isaiah 2:4: "They shall beat their swords into plowshares, their spears into pruning hooks."

On Sept. 9, 1980, the Berrigan brothers and six others entered a General Electric nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, and hammered on the unarmed nose cones of some Mark 12A warheads. They also poured blood on blueprints and papers.

In an essay about the first Plowshares action, Berrigan explained his use of blood in the GE plant and in his numerous arrests at the Pentagon, often for pouring blood on the pillars, doors and walls.

"We pour our blood at GE in order to proclaim the sin of mass destruction," Berrigan wrote. "Our blood confronts the irrational, makes megadeath concrete, summons the warmakers to their senses."

In all, Berrigan had six Plowshares actions to his credit, while helping to recruit actors and planning many others as an unindicted co-conspirator.

The aftermath of Berrigan's actions was captured in police photos, often showing the stark images of spilled blood and the empty plastic baby bottles used to carry the blood. After years of blood and spray paint being sandblasted off the columns of the Pentagon's River Entrance, there is now a distinct discoloring of the granite columns that is probably permanent.

Advertisement

Despite long periods of separation from his wife and three children, Berrigan took his roles as husband and father seriously, trying not to neglect his loved ones and giving intimate time to his children whenever he was at home.

In a recent Lenten essay published by Pax Christi USA, in a booklet titled, "A Fast that Matters," Berrigan's oldest child, Frida Berrigan, recounts the times her father read to her and siblings Jerry and Kate at bedtime.

"[T]his devout and dangerous man, once the FBI's Most Wanted, would sit in his rocking chair and read to us: The Hobbit, Tale of Two Cities, Little Women, James Herriot's stories of being a country veterinarian," Frida wrote.

We'd sit rapt, listening to his stentorian voice ... But, once a week, this precious gift would be interrupted by dreaded, boring old Bible study. We'd read aloud a passage he picked out of the Gospels and then he'd question us like we were catechism students. ... Looking back on these weekly Bible studies I always wish I had listened better, taken notes, and given more attention to these mini-Solentiname style study sessions.

Berrigan's writing also took on a prescient character as he often saw the writing on the wall when it came to the negative impact of war-making on the global community.

"The greatest assault on the environment comes from military sources," Berrigan wrote in 1993, a claim increasingly drawing attention. "The greatest poisoning of our air, soil and water comes from war and preparation for war. Can it be that our hatred for one another, represented by nuclear and conventional weapons, puts us at war with the earth, making us wasters and despoilers of the earth? Exactly so."

Throughout his writings, Berrigan called for a nonviolent revolution to stop militarism, while referring to himself as a revolutionary.

"In a word, I believe in revolution, and I hope to continue making a nonviolent contribution to it," Phil wrote in 1971. A Ministry of Risk makes the case that Berrigan stayed true to his word.