Arielle Jacobs as Imelda Marcos in "Here Lies Love" (Billy Bustamante, Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

Summer is the cruelest season on Broadway, months during which shows grit their teeth, make themselves as attractive as possible to the tourists mobbing TKTS, and pray to survive. Not every show does. This summer, "Camelot," "New York, New York," "Bob Fosse's Dancin'," "Life of Pi," "Peter Pan Goes Wrong," "Once Upon a One More Time" and "Bad Cinderella" all have finished what were meant to be open-ended runs, some just weeks after they began.

But in the midst of such struggles, one musical opening this summer is drawing a lot of interest, both for its style and its subject matter.

"Here Lies Love" is a disco-inspired musical about Imelda Marcos, wife of Filipino president and later dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Created by American pop icon David Byrne and English DJ Fatboy Slim and developed and directed by Tony-winner Alex Timbers, the show follows Imelda Marcos from her youth in rural Tacloban through her rise to power as first lady and later de facto leader of the country.

The staging of the show is unique: The theater's orchestra seating and stage have been removed and replaced with a Studio 54-esque dance floor on which those with orchestra tickets stand while the cast performs on movable platforms slightly above them.

As Byrne was first imagining the show, he told The Washington Post recently, he learned that Imelda Marcos had loved Studio 54. She even had a disco ball hanging in her New York City townhouse. "What if that's how the story gets told?" he asked himself. "The play is in a club. We give it that heady, frothy environment."

Byrne and Timbers really lean into their concept. Not only is the audience on the floor and in the mezzanine invited to dance along at times, but in almost every scene, the characters' attention is specifically on them. Some moments are fashioned as political rallies, others as presidential visits or parties.

Whatever the occasion, there are few "private" moments in "Here Lies Love." Everything is performance.

That approach is meant to offer the audience a felt sense of what it was like to be in the Philippines under the Marcoses, to experience for themselves the giddy seduction Imelda and Ferdinand offered via their extravagant spending while the poor suffered and the nation went into debt. And it truly is a dazzling experience to be so close to the performance, even interacting with the performers.

Similarly, when public opinion turned against Marcos and he suddenly declared martial law — a situation that would eventually see tens of thousands of Filipinos arrested and tortured, and thousands killed — the audience finds itself in the midst of the chaos that Filipinos experienced. What seemed like a party is revealed to have been a cage from which there is no escape.

Arielle Jacobs as Imelda Marcos in "Here Lies Love" (Billy Bustamante, Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

But Byrne's immersive strategy also means that we don't get many meaningful glimpses at the inner life of the characters.

Even the show's "hero," politician Ninoy Aquino, who speaks out against the Marcoses repeatedly, is only allowed to be more than a stock politician briefly, at the end of his life. Most of his appearances are just as clearly crafted to generate support as the Marcoses' are, even playing at times on the same natural enthusiasm of the people. Conrad Ricamora gives the role "young Obama" energy.

Imelda's situation is far different. Over the course of the musical, we watch a young girl become a vicious tyrant. Was she headed down that path from the beginning? Did she know what she was getting into with Marcos? Was she manipulated? Or did she make compromises that eventually transformed her into someone far different than she wanted? It's hard to say.

In the few private moments the show affords Imelda (played with tremendous vivacity by Arielle Jacobs), there's a tendency to present her in the most innocent of ways. Perhaps those choices are meant to be a corrective to the context the show creates: If Imelda didn't have an inspiring princess-like quality — her first song perfectly apes the modern animated Disney songbook — would the audience judge her constant eye toward the crowds as manipulative, as we judge Ferdinand Marcos? But the result is that she comes off quite sympathetic, even as the story turns.

More puzzling is the fact that the show makes no mention of the role of Catholicism in either Imelda's life or the life of the country.

Advertisement

Ferdinand Marcos officially ended martial law in 1981 — if in name only — almost entirely so as to convince Pope John Paul II to visit, something Imelda had been trying to make happen for years. (The behind-the-scenes political machinations of that visit are themselves a story worthy of attention.)

The Catholic Church also served as a key voice of opposition during Marcos' reign. In 1986, Filipino Cardinal Jaime Sin's request that Catholics surround a military base in order to protect two military defectors from Marcos' troops instigated the four-day People Power Revolution that would bring the Marcos government down.

Time Magazine describes those days: "Nuns could be seen in the streets, praying over their rosary beads as they placed flowers in the barrels of soldiers' guns. Priests mediated between angry protesters and fraught military men. As one of the few media outlets to have survived Marcos' crackdown on the press, Radio Veritas [the church's radio station] broadcast minute-by-minute coverage of the uprising."

The show mentions none of this. In fact, it presents the People Power Revolution immediately after the assassination of Aquino, and a subsequent rally led by his mother, as though that were what led to the Marcos' downfall, when those events actually happened three years prior to the end.

The show ends on a country-esque song that stitches together the real-life testimony of different people who were there when the Marcoses' helicopter flew away. Its pretty but banal refrain is as close as the show gets to religion: "You might think that you are lost / But then you will find / That God draws straight / But with crooked lines."

Experienced live, performed by the entire cast now performing as themselves rather than their characters, the number is undeniably moving. But "Amazing Grace," this is not.

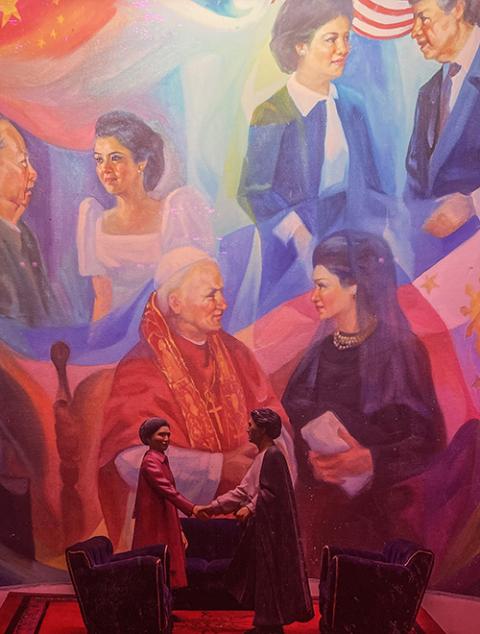

In the lounge in the basement of the theater hang photographs of dioramas that David Byrne discovered when he visited the Santo Niño Shrine that Imelda Marcos had built in Tacloban, the Philippines. (Courtesy of Jim McDermott)

And yet even if the creators seem allergic to the Catholicism at the heart of their story, they're unable to fully suppress the traces of that reality or Imelda Marcos' ambition. In the lounge in the basement of the theater hang photographs of dioramas that Byrne discovered when he visited the Santo Niño Shrine that Imelda Marcos had built in Tacloban.

Designed by the shrine's architect, these dioramas depict scenes from Imelda's life that she wanted remembered. They clearly follow the storyline of a saint's life — a childhood in poverty; being crowned a beauty queen, foreshadowing her later role in the country; doing good deeds for the poor as first lady; meeting the pope.

Imelda Marcos had 14 such dioramas built — the same number as there are stations of the Cross. In a country where Catholicism was so fundamental to the language of the people's imagination, it's impossible to believe that choice was coincidental. Imelda wanted to be understood as not only a saint but a messianic figure.

Writing in American Theatre, Filipina American playwright Amanda L. Andrei describes the complicated tradeoff offered by "Here Lies Love." On the one hand, she describes "feeling uneasy and slightly sick" after seeing the original production of the show at New York's Public Theater 10 years ago. She wondered "why Imelda seemed to be portrayed as a victim of circumstances and why there was very little mention of the Marcos regime’s human rights violations."

But on the other hand, Andrei and others have noted the "historic first" that the show offers Broadway, "an all-Filipino cast and majority Filipino creative team." And that truly is one of the most thrilling elements of the show. The performers are tremendous, and this show represents both a long-overdue opportunity and a claiming of place. Filipino artists have stories of their own to tell, and they belong here.

While more and more of Broadway is populated with tired remakes of movies, "Here Lies Love" is a truly unique and thrilling theatrical experience — a show with fresh and bold aspirations. On its Instagram feed, the show proclaims that it intends to offer "an innovative template on how to stand up to tyrants."

At the same time, the show's reluctance to prosecute Imelda Marcos and its total erasure of Catholicism from the story are moves troublingly close to the tactics of the tyrants they denounce.

A musical is not a documentary. But it certainly is a seduction. And "Here Lies Love" is a passionate warning of the dangers of being swept off your feet, in more ways than one.