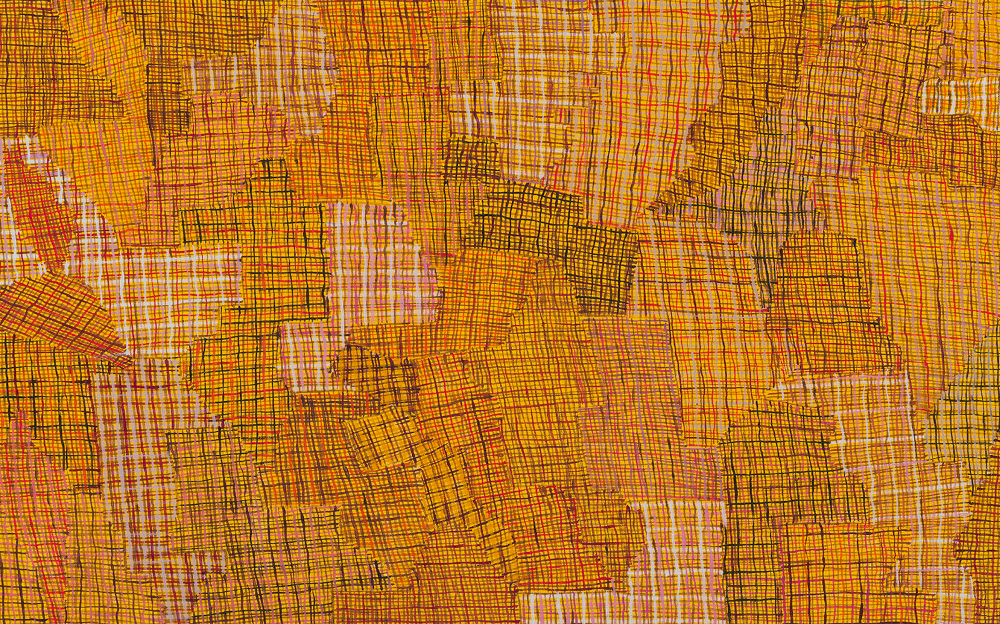

Regina Pilawuk Wilson, "Syaw (Fishnet)," 2014 (Sid Hoeltzell)

In the late 1920s, when Chicago artist Ivan Albright sat to paint a full-length portrait of Peter Haberlin, a Franciscan monk at Mission San Luis Rey in Oceanside, California, the painter asked, "Can't you feel more religious?"

The monk responded, "I'm doing the best I can," notes a wall label in the exhibit "Flesh: Ivan Albright at the Art Institute of Chicago" (through Aug. 5).

The painting, titled "I Walk To and Fro through Civilization and I Talk as I Walk (Follow Me, the Monk)," is one of the least bizarre works in the one-room exhibition, which celebrates an artist whom the Art Institute describes as "one of the most provocative artists of the 20th century, a 'master of the macabre' famous for his richly detailed paintings of ghoulish subjects."

Albright (1897-1983) became one of the most famous American painters after his "Picture of Dorian Gray" was used as a prop in the 1945 Oscar-winning adaptation of Oscar Wilde's 1891 novel. Albright's picture, per Wilde's description before him, is downright terrifying and is difficult to describe to someone who hasn't seen it in person. The life-sized figure, it might be said, looks like he has just emerged from a losing paintball match, during which he has also sprouted an abundance of boils. The environment itself has turned on the figure, and Albright has somehow managed to endow every nook and cranny of the picture with such an off-putting aura that one can't help but recoil, without entirely knowing why.

Typically, the painting hangs on its own directly opposite the crowd-pleasing "Nighthawks," by Edward Hopper, but in the Albright exhibition, it's among its brethren, including highly unflattering self-portraits, a picture of Mary Block (co-namesake of Northwestern University's museum) that it's hard to imagine anyone could find flattering, and a painting titled "Into the World There Came a Soul Called Ida." The latter is a ghastly take on Renaissance traditions of showing attractive young women eyeing mirrors or combing their hair as death looks on, often bearing an hourglass. Where other artists might be tempted to smooth over embarrassing features or to darken a sitter's hair, Albright likely introduced unseemly bulges, and worse, where none really existed.

Ivan Albright, "Picture of Dorian Gray," 1943-44 (The Art Institute of Chicago)

The portrait of the monk, however, is more humanizing. The monk's face and hands are wrinkled, but there's a majesty to the man, who bears a crucifix. His eyes downcast, the monk stands in a sparsely decorated room, facing some light pouring in through a window. A small plant on the sill echoes, in its sagging leaves, the monk's dangling rosary beads and knotted cord. Where other pictures in the show repel, this one draws the viewer in, and an exhibit label suggests spiritual transcendence.

Albright is up to something very different in "And Man Created God in His Own Image," where a man wearing a hat removes his shirt. This depiction, the exhibit notes, is anything but a classical male nude. What it presents, a wall label states, is a controversial and "disturbing vision of 'God' made flesh," in which Albright worked from an Illinois labor leader and bartender named George Washington Stafford.

Critics at the time referred to the "Bowery bum" and "bleary-eyed, red-faced, elephant-skinned reprobate." And yet, the exhibit suggests, the artist meant for the picture to convey nuance: "Is the main figure a symbol of humanity's delusions in thinking itself divine?" it asks. "Or is the true nature of God to assume the form of society's most wretched and outcast members?"

Exploring the notion of what it might mean — at least pictorially — for the divine to assume flesh in the context of Wilde's novel, in which flesh becomes immune to aging through a kind of reversed, aesthetic voodoo doll, is a heavy enterprise that is not for the faint of heart. More than 650 miles away, at Washington's Phillips Collection, the opposite sort of program emerges in the exhibit "Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia" (through Sept. 9).

Among the nine artists in the show, several were exposed — involuntarily — to Catholic teachings as children, when missionaries sought to replace their indigenous heritage with European, Catholic culture.

Regina Pilawuk Wilson, who was on hand from Australia at a press preview of the exhibit and whose large, meticulous paintings draw upon traditional weaving techniques, told NCR about how Catholic missionaries sought to erase language and culture. As an adult, Wilson and her husband left the mission in Daly River, where they were brought involuntarily, and some 250 people came with them on their exodus to found a new community more than 60 miles away.

"We didn't like the way the missionary was telling us what to do," she said.

The exhibition catalog adds that Wilson wasn't alone in remembering the nuns' and missionaries' cruelty. "She and her peers wanted a life closer to that of their parents," the catalog states. "They wanted to be able to raise their children according to their traditional belief systems, and in ways dictated not by the church, but rather by the order and rhythms of the land to which they belong."

Advertisement

Whether artmaking was encouraged depended on the personality of the missionary, explained Henry Skerritt, curator of indigenous arts of Australia at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia. "In Milingimbi, for example, people talk very fondly of the missionaries Wilbur Chaseling and T.T. Webb, who were really instrumental in getting the art movement there," he said. "Other missions were much more determined to get everyone wearing white shirts and working in the gardens."

Hector Jandany is an example of an Aboriginal artist (not included in the exhibit) who drew upon both Catholic and indigenous symbolism. At first glance, Jandany's painting of Jesus rising from the grave presents an abstraction. A kind-of "rainbow" of ochres, umbers and blacks looms above a small white figure, set against a black background. But the scene references the Bible, even as its style owes a lot to indigenous techniques.

"We always knew about Ngapuny (God) and the spirit, but youse mob had to tell us about Jesus and Mary," the artist told the Australian curator Mercy Sr. Rosemary Crumlin, notes the Sydney Archdiocese's website.

Jandany, and other artists, would carry paintings under their arms to schools as learning aids for the children, according to Crumlin. "They'd teach them songs and dances and tell them about Dreamtime and Christian Dreamtime," she said. Dreamtime, in Aboriginal mythology, is a time with beginning but without end when mythic beings shaped the world.

Ivan Albright, "I Walk To and Fro through Civilization and I Talk As I Walk (Follow Me, the Monk)," 1926-27. (The Art Institute of Chicago)

It isn't just unique that Jandany and Queenie McKenzie Nakarra, a fellow artist from the Western Australian region of Warmun, blend indigenous heritage and Christianity. But unlike other communities in the country, which is about the size of the continental U.S. and is home to many different peoples, Warmun wasn't under the watchful eye of missionaries. Instead, an elder brought the faith to the community.

Crucifixions and pictures of Mary and the like don't surface in the Phillips exhibit, but it's impossible to consider the work without addressing the context of missions.

"Many church personnel saw salvation as only available within their own European cultures, even though this was demonstrably inconsistent with the church's well-established teachings on culture and dignity," said Dominic O'Sullivan, associate professor of political science at Charles Sturt University in Australia and author of the book Faith Politics and Reconciliation: Catholicism and the Politics of Indigeneity.

While some Catholic missionaries opposed bringing kidnapped children into their institutions, when told by government officials that those children, if not accepted, would be sent to Protestant missions, many caved, seeing the latter option as a sure road to damnation, according to O'Sullivan. "A lesser of two evils argument was accepted," he said, noting that culpability still abounds.

"It would be uncommon for Aboriginal people to see the church as theirs," O'Sullivan said, calling Australian church leaders — particularly in their addressing the present sexual abuse scandal — "aloof, out of touch and distant from the people."

After a time of great hope in the 1990s, the church appeared to have lost interest in indigenous peoples, and it ought to seek to reconcile with them and "allow them to make the church their own and to see an authentic Gospel of hope and love," he said.

Skerritt, the exhibit curator, sees reconciliation in some of the work that indigenous artists have made, even when they draw on Christian themes. "What's really interesting when you look at that work," he said, "is that the artists didn't abandon their 'dreaming' cosmologies. Christianity just kind of came and was incorporated into it as part of it."

To the artists, the "dreaming" worldview was larger than organized religion, and it permeated all aspects of their lives. It was, in short, embedded in the Earth itself.

Where Albright's work takes beautiful flesh and renders it inhuman, the artists in the Phillips exhibition take earth and plants and present them in elevated fashion.

"Everything in the land is created by the ancestral beings," Skerritt said. "Everything has ancestral presence: Every tree and animal has ancestral identity."

That is why, he added, the artists used materials from the earth, which would inevitably decay, when they create work about the Earth. For them, form really did follow content, or put differently, the boundary between flesh and the divine was rendered quite blurry.

[Menachem Wecker is a freelance reporter in Washington, D.C.]