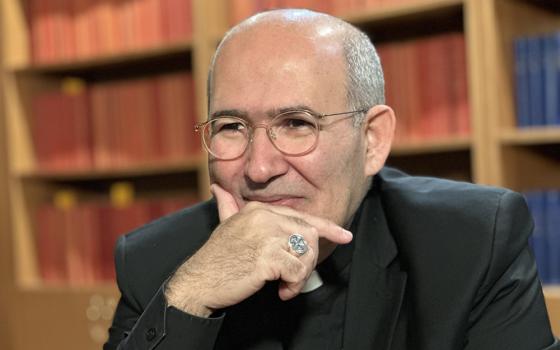

Cardinal Pietro Parolin celebrates a Mass marking the 50th anniversary of Italy's Movement for Life in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican March 8, 2025. (CNS/Pablo Esparza)

When Pope Francis appointed Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin at age 58 as Vatican secretary of state in 2013, he became the youngest person to hold that position since Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli was named to the post in 1930.

Pacelli went on to become Pope Pius XII in 1939; a Vatican secretary of state has not been elected pope since then. Nearly a century later, could history be about to repeat itself?

The case for Parolin is at once simple and complicated. For more than a decade, he served as Francis' top aide and by all accounts was a loyal deputy. And for some time, it seemed as if a Parolin candidacy would likely be favored by those who wanted to continue in the same pastoral direction as Francis, but with the more predictable temperament of a career diplomat.

But in the final years of the Francis papacy, Parolin's stock was on the rise among more traditional-leaning prelates. They have taken a keen interest in some of the cardinal's carefully crafted statements that some have interpreted as a desire not just to steady the ship but to reverse course.

During the first session of the synod on synodality — Francis' summit on the future of the Catholic Church — in October 2023, Parolin gave a passionate speech on the need not to abandon the church's long-standing moral teaching, according to many participants, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

These people said that Parolin's comments were widely interpreted as a rejection of the push for a more welcoming church for LGBTQ persons and expanded roles for women's leadership.

Those suspicions were only heightened in January 2024, when the cardinal was asked about the pope's controversial declaration allowing for priests to bless individuals in same-sex unions. In the immediate aftermath, prelates in Eastern Europe and Africa had sharply criticized the move, and a reporter pressed Parolin on whether Pope Francis had made a mistake.

The cardinal, who has reflexively always defended the pope, offered a more muted response, only saying, "I do not enter into these considerations."

"The reactions tell us that it has touched a very sensitive point," Parolin added.

Pope Francis and Cardinal Pietro Parolin talk as they leave the opening session of the Synod of Bishops on the family at the Vatican Oct. 5, 2015. (CNS/Paul Haring)

An example of Parolin's role as enforcer defending traditional church teaching has been seen in recent years in his response to the German Synodal Way. That yearslong series of meetings on church reform has advocated for more progressive stands in Germany on issues such as LGBTQ inclusion, women's ordination, and clerical celibacy.

Typically, the role of enforcer would fall to the Vatican's doctrinal office. But in the case of Germany, Parolin has stepped in. While Francis expressed his concerns that the process was out of sync with Rome, Parolin has been more forceful in his reminder that on homosexuality and women's ordination, the church's teachings are "nonnegotiable."

Two major issues, however, stalk his candidacy: China and Vatican finances.

Parolin was one of the primary architects of the Vatican's controversial agreement with China that was signed in 2018 — originally for two years and now twice extended. Parolin received accolades from those eager to cheerlead the accords, which allowed all of the bishops in China to be in communion with Rome for the first time in decades. It was Parolin who during the papacy of Benedict XVI first reestablished formal contact between the Vatican and Beijing.

While the contents of the 2018 agreement have been kept secret, it is broadly understood to give the Holy See final approval over the appointment of bishops in China after years of having no real control over Catholic leadership in the world's most populous country.

Cardinal Pietro Parolin speaks at a symposium on religious freedom hosted by the U.S. Embassy to the Holy See in Rome April 3, 2019. (CNS/U.S. Embassy to the Holy See/A.J. Olnes)

Critics, including former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, complain the secret pact seems to force the church to be silent on the country's aggressive and often violent crackdown against Catholics and people of other faiths.

In 2020, Parolin seemed to make a serious blunder when he insisted Chinese Catholics are "not persecuted," despite a mountain of evidence to the contrary, prompting immediate pushback from advocates of Chinese Catholics.

One of Parolin's fiercest critics has been retired Cardinal Joseph Zen of Hong Kong, a prominent conservative, who has lambasted the Vatican — and Parolin explicitly — as capitulating to China's human rights abuses.

While Zen, 93, no longer has a right to vote in a conclave because cardinals over the age of 80 are no longer electors, his voice and those concerns will likely still be present in the Sistine Chapel.

Conservative Catholic commentator George Weigel, who was unsparing in his criticism of Francis in his final years, has warned that the China question should "raise serious issues for those who imagine Cardinal Parolin as Pope Francis's successor."

On another front, those who enter this conclave with a long memory might also have flashbacks to the 2013 election of Francis, when the cardinals had identified reform of the Vatican's rapidly depleting financial patrimony as one of the key issues facing the new pope.

That project is far from complete and many questions still linger about the Vatican's ill-advised real estate investment in a London property that went belly-up, ultimately resulting in the loss of more than 200 million euros.

While a Vatican court ultimately convicted Sardinian Cardinal Angelo Becciu for his primary role in the debacle, the fact that Parolin was aware of and approved the transactions is likely to cast a shadow over his candidacy for those still concerned about financial reform.

Parolin was born in 1955 in the northern Italian region of the Veneto to the son of a hardware store manager and an elementary school teacher. Parolin's entire adult life has been spent in church governance, with no direct pastoral experience.

Advertisement

Following his graduation from the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy, the Vatican training school for diplomats, he served in Nigeria, Mexico and Venezuela, as well as a previous stint as the Vatican's undersecretary of state for relations with states. Along with his native Italian, the cardinal speaks English, French and Spanish.

Some diplomats who have worked with him and have spoken to the National Catholic Reporter on the condition of anonymity have complained that he can be indecisive and often lets files pile up on his desk, creating a backlog within the Curia and Vatican embassies around the world. Still, he is widely regarded as capable and competent when it comes to understanding the geopolitical sphere.

Inside the church, his long-standing service means that he will enter this conclave with immediate name recognition, giving him an advantage among a group of men who have not had the opportunity to get to know each other well.

Now 70, Parolin was hospitalized for surgery on an enlarged prostate in 2020. Those who see him regularly comment that he often appears to be in frail health. Those conditions, combined with his gentle, reserved manner, might be viewed as just what the doctor ordered after a pope who dominated the spotlight but left his aides and even his allies exhausted at times.

After three non-Italian popes, there is strong desire among many Italians to see the papacy return to the country that has produced by far the most pontiffs — although that's a sentiment not widely shared beyond Italy. For an Italian to be elected, however, the Italian electors would need to be strongly united behind one candidate and vote as a solid bloc. Because Bologna Cardinal Matteo Zuppi also is a much-discussed candidate — and disagreement being a favorite Italian pastime — Italian unanimity seems unlikely.

But then again, diplomatic coups are always possible. In a deeply polarized church, the cardinals may look to one of its top ambassadors to broker a peace deal at home.

This is part of a series on the leading candidates in the 2025 papal election. The National Catholic Reporter's Rome Bureau is made possible in part by the generosity of Joan and Bob McGrath.