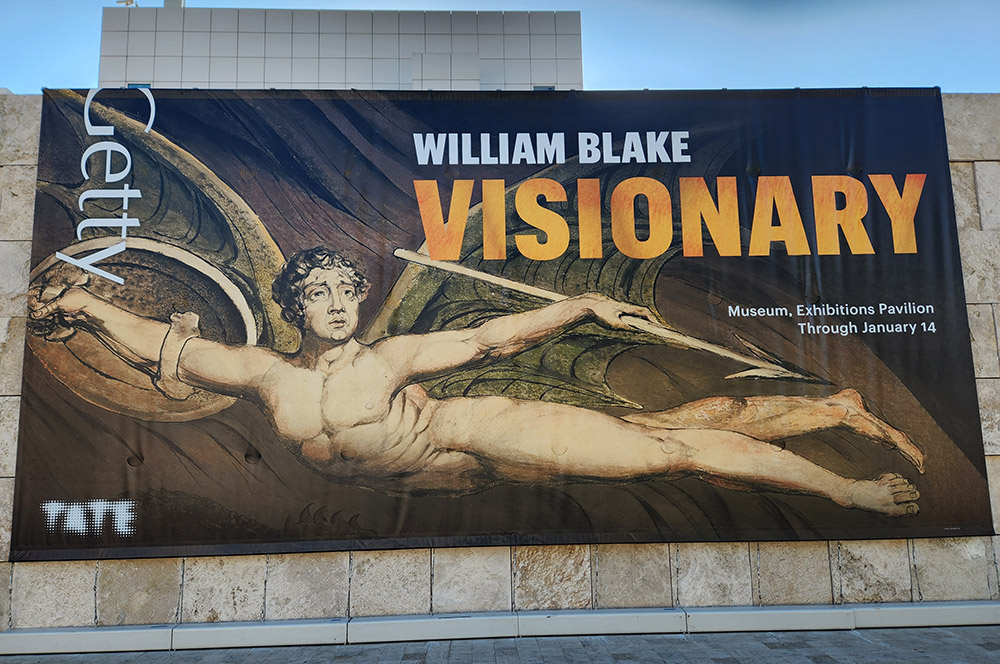

An outdoor banner for the exhibit "WIlliam Blake: Visionary," at the G. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, features a detail of the 1795 print "Satan Exulting over Eve." The exhibit is on display through Jan. 14, 2024. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

My encounters with the work of the early English Romantic painter, engraver and poet William Blake (1757-1827) have been marked by respect, awe and sometimes bewilderment.

Respect and awe because both Blake's poetry and visual art are grounded in a unique, single-minded perspective that, to the reader and art lover, are not easily categorized — visionary, spiritual, aspirational, remarkable in their moral integrity.

But those are also the reasons that sometimes, particularly in the visual work of prints and paintings, Blake's unconventional visual art can bewilder and confound.

And that's all right, as I found out during a recent afternoon at the J. Paul Getty Museum, which is currently hosting a major exhibition on Blake's work titled "William Blake: Visionary," now on view at the Los Angeles museum through Jan. 14, 2024.

William Blake's religious views were complex, even contradictory.

"Radical, fantastical, and unforgettable," Timothy Potts, the director of the museum said in a statement about the exhibit. "Blake's works will make visitors feel they have been transported to another world."

They do — and in ways that can make an art lover feel spiritually renewed.

More than 100 works are on display in this collaboration with the famed Tate Britain in London. The Getty's "William Blake: Visionary" is being called the first major international loan exhibition on Blake on the U.S. West Coast — an event that had been originally slated to open in 2020 but was delayed due to the global pandemic.

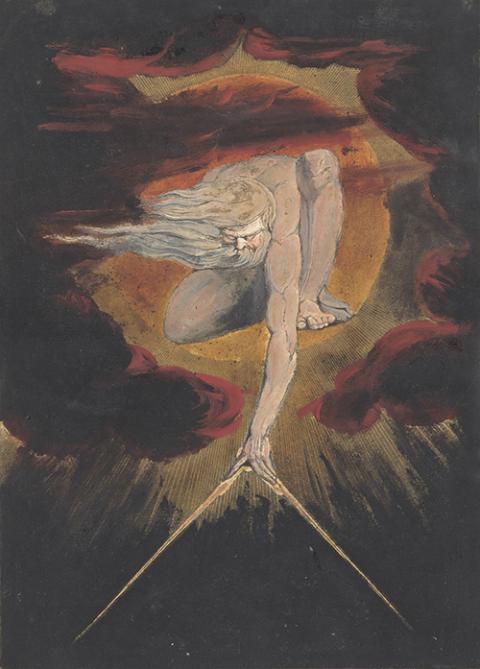

“The Ancient of Days,” from "Europe a Prophecy," printed 1795, William Blake (British, 1757–1827), color-printed relief etching in dark brown with pen and black ink, oil, and watercolor (Courtesy of Getty Museum)

It was worth the wait. I've seen some of the works before, including at the Tate, but it was inspiring to see so many Blake works exhibited together.

In exploring what the Getty calls "Blake's wild imagination," the exhibit gives proper grounding to his historical context. As noted by art scholars Edina Adam and Julian Brooks in their introduction to a catalog accompanying the exhibit, the Great Britain of Blake's era underwent "significant political, economic and social changes," including three major military conflicts on five continents. Among those conflicts, of course, was the 1765-83 American Revolution.

Religious divisions, too, marked the era. As the introduction notes, Catholics, Jews and dissenting Protestants — those who "did not conform to the practices of the Anglican Church" — had limited rights, which was also true of all women and of men who were not property owners.

But the era was perhaps most marked by some of the same contradictions and challenges of our own time. Though Great Britain experienced great prosperity, the catalog's introduction notes that "wealth was distributed unequally, and the disparity between the classes grew, resulting in social unrest."

"Blake bore witness to these changes," Adams and Brooks note, and saw London transformed into a megalopolis in which the traumas of economic disparity were glaringly apparent.

Some of this was expressed vividly in poetry that often took a bold turn from much of the neoclassical verse of the 18th century. Blake's work became grittier — not afraid to offer social critique, as the first two stanzas of Blake's 1794 poem "London" demonstrate:

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear

In this and other ways, Blake — whose own family were Protestant "dissenters" — took on both the political and religious powers of his time and wasn't afraid to be contrarian and embrace novelty.

Advertisement

It shouldn't surprise that while Blake was educated at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, he always felt himself to be an outsider and chose not to embrace the popular genre of oil painting, which won acclaim for his contemporary J.M. William Turner (1775-1851).

I find that a bit sad — no one can question Blake's talent and versatility in printmaking, tempera and watercolor, but imagine what he could have done had he embraced oil painting — and on the scale Turner so masterfully pulled off.

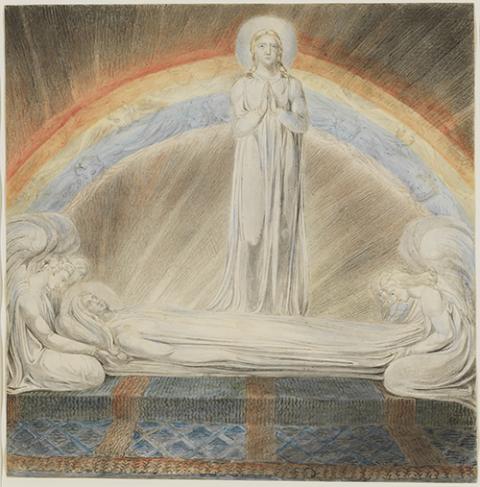

"The Death of the Virgin," 1803, William Blake (British, 1757–1827), watercolor (Courtesy of Getty Museum/©Tate)

As it is, the Getty exhibit does a fine job of exploring Blake's spiritual vision — which had its roots in Christian and classical imagery, but was singularly unique. Blake turned to the Bible for inspiration — the exhibit has no shortage of biblically inspired images, such as "The Death of the Virgin," an 1803 watercolor, and "Satan Exulting over Eve," a 1795 print that serves as something of the exhibit's centerpiece.

As the Getty notes in its description of the exhibit, Blake's religious views were complex, even contradictory. Blake rejected the idea of God "as an omnipotent patriarch or vengeful deity," the museum said. "Rather, he identified as a spiritualist and claimed to have experienced frequent visions."

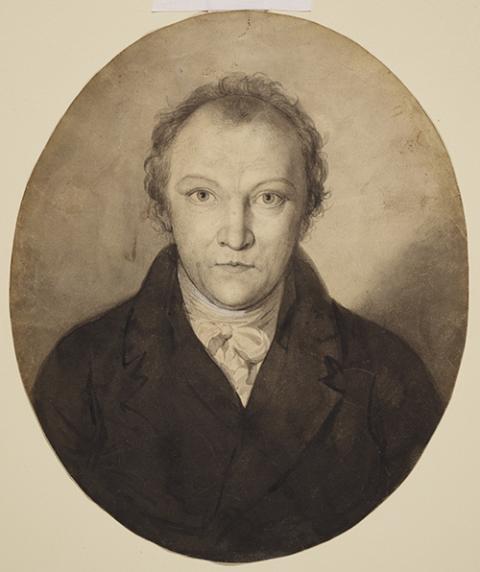

Something of Blake's spirit comes alive in a self-portrait on display — a work that suggests an alert, intense man intent observing the world around him with a hypnotic, straight-ahead gaze.

To many, Blake was a forerunner of counterculturalism.

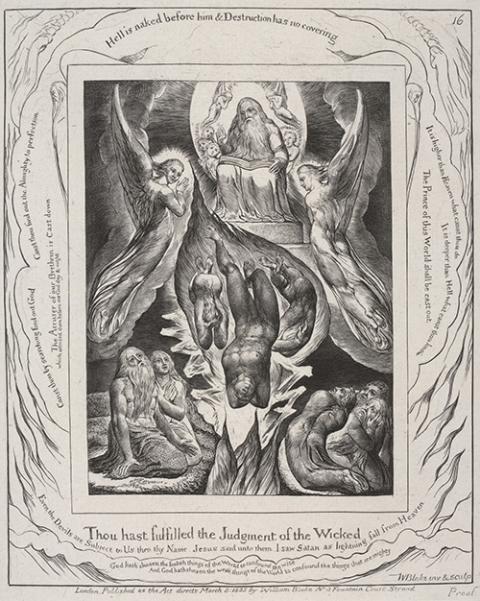

Plate 16 from "Illustrations of the Book of Job," printed 1825, William Blake (British, 1757-1827), engraving (Courtesy of Getty Museum)

"William Blake's deep spirituality, questioning nature, and vivid imagination particularly resonated with poets and musicians of the 1960s and 1970s such as Allen Ginsberg, Patti Smith, and Bob Dylan," said Brooks, who is the Getty's senior curator of drawings. "Yet Blake's work continues to pop up in many unexpected places too, and it feels eternally relevant."

As a poet, I found Blake's printmaking that combined his original verse with intricate detailed images— a genre he called "illuminated books" — arresting. What poets would not want their verse illustrated with such care and love?

But for me, the exhibit's highlight was Blake's masterful prints of the story of the Book of Job. I kept returning to them again and again during the afternoon I spent at the museum. Beautifully detailed, these works display both humanity and majesty.

In depicting a well-known Biblical narrative of a man beset by suffering and despair, Blake's Job is rendered with a cosmic backdrop — both moving and stirring.

Brooks said the museum hopes "William Blake: Visionary" will leave visitors "feeling empowered to explore the boundaries of what can be imagined."

Thanks to the Getty and to William Blake, I certainly did.