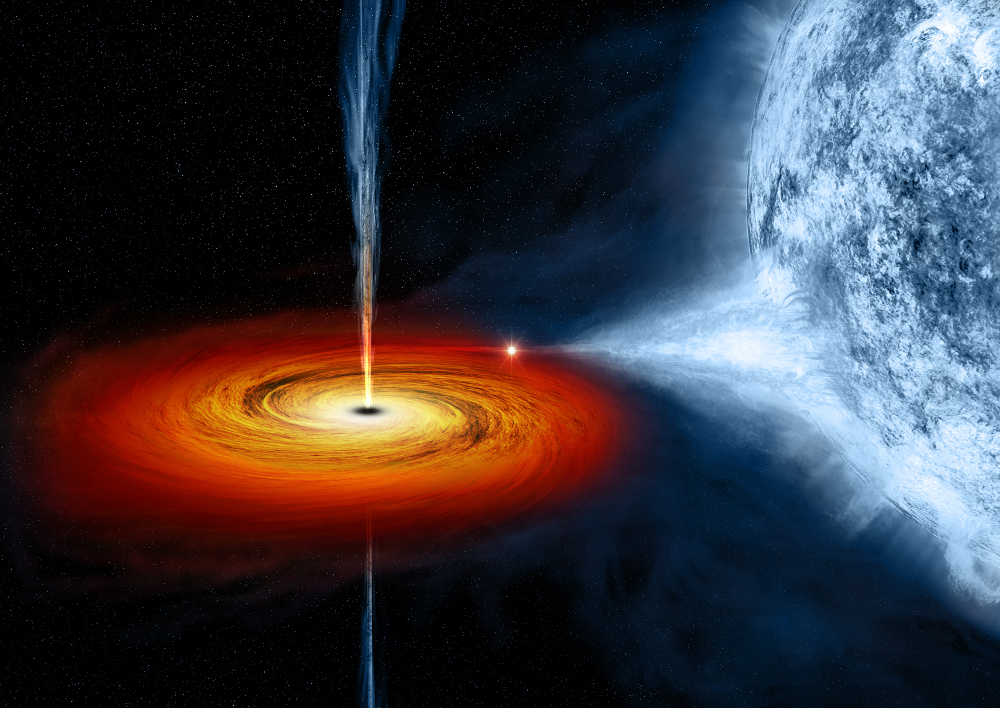

Illustration of Cygnus X-1 (NASA/CXC/M.Weiss)

Alan Lightman, professor and author of more than 15 books, including the best-selling novel Einstein's Dreams, says he is not a believer in God. But he wishes he were.

If there's a theme to this wide-ranging book, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, that's it. Part memoir, part scientific observation, part discussion of religious and metaphysical beliefs, the book contains 20 chapters focusing on topics like origins, atoms, ants, motion and truth.

Under these headings, Lightman discusses many things using religion and science, including the basics of Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam and Christianity and the findings of scientists like Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

To the mix, he adds his own personal experiences, which makes this poetically written though challenging book more palatable for a nonscientific reader, especially when he considers subjects like the end of life.

Death, he writes, is the gradual diminishment of consciousness. According to science, a person is made of about seven thousand trillion trillion atoms. "The totality of our tissues and muscles and organs is composed of these atoms. And, according to the scientific view, there is nothing else," he says. We are "simply assemblages of atoms. And when we die, this special assemblage dissembles."

Amid such considerations, Lightman recalls his deceased parents — his loving father and his mother, who liked to dance the bossa nova and shake her hips just so. He doesn't believe he will see them in an afterlife. He wonders about his own death as well. Lightman writes that he had to take a walk after writing this chapter; this makes the subject even more poignant.

Lightman also shares his experiences studying for a doctorate in astrophysics at the California Institute of Technology. He recalls the excitement when Cygnus X-1 (the first black hole) was discovered in the early 1970s.

As a budding astrophysicist, he worked with Einstein's equations for gravity as well as other equations describing gas flow, radiation processes and thermodynamics. He learned among other things that Cygnus X-1 was located about 7,000 light years from Earth. Later, he applied those equations to other newly discovered black holes.

Alan Lightman (Pantheon/Michael Lionstar)

But, he says, explanations that work today may not work tomorrow. Science doesn't deal in certainty so much as in the search for certainty — which, he suggests, makes science more similar to religion than scientists like to admit. He explains that some scientific principles endorse absolutism — those principles that people believe but cannot prove by laws of science, like the concept of the self and soul — which Lightman considers an illusion.

Lightman is Jewish and argues with a rabbi friend. He doesn't believe the truths of sacred texts or the teachings of many religious thinkers. He disagrees with Aquinas and argues with Augustine about sin and free will. He seems to misread a Vatican II assertion concerning truth in Scripture, which says only those statements deemed essential to salvation are literally true — not everything in the Bible, as Lightman incorrectly implies.

He does believe in the personal transcendent experience and quotes William James who said, "Having once felt the presence of God's spirit, I have never lost it again for long." Lightman calls this experience, "the most powerful evidence we have for a spiritual world." It's an "immediate…feeling [of] some unseen order or truth in the world." Lightman says he's had several transcendent experiences — one inspired this book's title.

Several years ago, he was in a motorboat in the Atlantic Ocean heading to an island. He cut off the boat's engine and, lying back, looked up at the night sky feeling at one with the universe. "After a few minutes," he says, "my world had dissolved into that star-littered sky. The boat disappeared. My body disappeared. And I found myself falling into infinity. … I felt a merging with something far larger than myself."

The occasion is especially noteworthy since Lightman, who even though he teaches creative writing and has written novels and published poetry, is primarily an astrophysicist who believes the universe is composed of physical substances controlled by laws.

The experience reminded him of Vincent van Gogh's painting, "The Starry Night," which Lightman discusses in a chapter on motion. He describes the painting — stars "with exaggerated halos" — so evocatively that it made me think of "The Starlight Night," a poem by Jesuit Fr. Gerard Manley Hopkins, written not too long (1877) before van Gogh painted his picture (1889) and may have inspired the artist.

Advertisement

Interestingly, van Gogh, who also rejected organized religion, once wrote a letter (which Lightman quotes) speaking of his "tremendous need for, shall I say the word — for religion — so I go outside at night to paint the stars."

Lightman says "The Starry Night" is one of his favorite paintings, but he doesn't explain why. Then again, he doesn't need to.

[Diane Scharper is a lecturer at the Johns Hopkins University Osher Institute. She is the author of several books including, Reading Lips and Other Ways to Overcome a Disability.]