Editor's note: This is the second part of EarthBeat's special series "An Estate Plan for the Earth," about how women's religious communities are conserving their land for future generations. You can read the first part here.

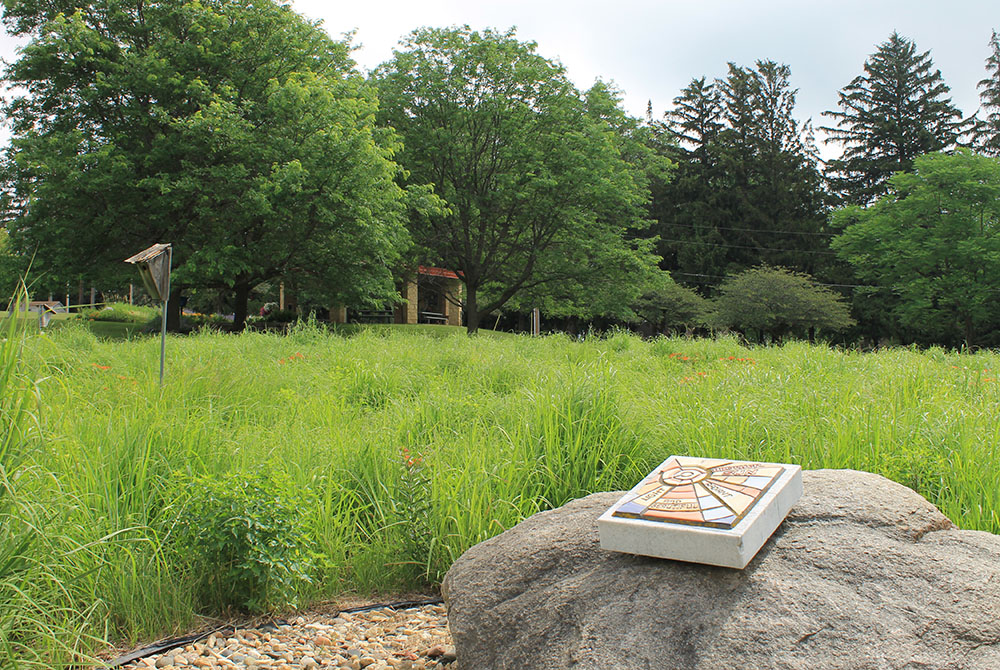

The sounds of nature swirl over the restored prairielands that blanket the north portion of land at the Mount St. Francis Motherhouse, home of the Sisters of St. Francis.

What was once farmland that sustained the congregation is now acres upon acres of native grasses and wildlife, with a mowed path, a section of overhead power lines and the city water tower in the distance among the few signs of human activity.

"We keep trying to get more flowers in there, to attract the birds and the butterflies and the bees," said Sr. Marie Cigrand during a late June tour of the land.

But although it appears wild now, this prairie oasis on a hilltop above this riverside city came about through human activity — or, rather, decision-making.

On May 17, 2019, the Dubuque Franciscans set aside 68 acres of the land for preservation in a conservation easement, capping several decades of land restoration and by law locking the land permanently into its natural state. Two months later, and nearly 200 miles to the north, their sister congregation, the Sisters of St. Francis of Rochester, Minnesota, did the same with the acreage around their own hilltop motherhouse.

While the motivations and the end result were the same, the two congregations chose different paths.

From farming to conservation

The Sisters of St. Francis have called Dubuque home since the 1870s and have been at their current location since 1878. They served the community as teachers and operated homes for orphans, the elderly and working women.

Initially, the sisters farmed and tilled the land themselves, then later rented it out to local farmers who grew hay and corn.

As Franciscans, the sisters have always felt a special connection with God's creation, following in the footsteps of St. Francis of Assisi. They believe land has its own intrinsic value beyond what it can produce or what can be done on it. Over time, those values and their love for the land guided them to consider other ways to manage it.

In 1988, the sisters restored 80 of their roughly 130 total acres as prairie. A decade later, they drafted a document called "Our Covenant with Creation," which outlined their values and spiritual connection with the created world, stating at one point "we are sisters and brothers with all creation."

"We believe that Clare and Francis, in their love and reverence for Jesus the Incarnate One, were led to experience all the created as holy and family, the dwelling place of Christ," the beginning of the document states.

The covenant also committed the sisters to "sustaining the whole ecological community" in their education efforts and choices they make. One of those choices came in 1999, when they placed 80 acres into the federal Conservation Reserve Program, which paid landowners not to farm or till environmentally sensitive land for periods of 10 to 15 years, and to restore it in ways that improve land and water quality and help mitigate climate change.

Participation in the Conservation Reserve Program helped lay the groundwork for the sisters to consider more permanent conservation options. By 2016, they had drafted another document, a land ethic that expanded on how they viewed creation.

"That was written to help us guide decisions as to how we would use our land in the future," said Cigrand, who served as vice president of the congregation from 2014 to 2020.

Within a year, the sisters began discussing a conservation easement. Under such an arrangement, the landowner agrees that the land will not be developed. In turn, the organization overseeing the easement, such as a local land trust, safeguards the land through annual visits.

Having worked with the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation in the past, they invited several representatives to speak at their fall 2017 congregational gathering. They later held a similar discussion with other congregations in the area.

At their spring 2018 gathering, the sisters agreed to go ahead with an easement. But that only began the process.

"We've had a lot of committee work and a lot of congregational input and so on through all these decisions that we've made," Cigrand said.

Advertisement

Guided by their land ethic and covenant with creation, the sisters moved swiftly through the easement process. One hurdle they faced was keeping straight the various stipulations about what could and could not be done with the land as dictated by the Conservation Reserve Program, easement regulations and other groups they had partnered with for preservation, such as the Wild Turkey Foundation. To get answers, they held a meeting with representatives from all the groups.

In May 2019, they finally completed the easement process with the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, permanently protecting 68 acres, 55 of which were prairie and 13 woodland.

"It wasn't a new idea. We'd been kind of growing into how do we want to preserve the land over years of experience," Cigrand said. "And you can count 40 years of our dedication to the land and care of the land."

Sr. Cathy Katoski, former president of the Sisters of St. Francis of Dubuque, Iowa, pets a goat at the edge of the congregation's property. The goats are part of a program to remove invasive species from the land, 68 acres of which has been placed in a conservation easement. (EarthBeat photo/Brian Roewe)

'This is a holy place'

The path to an easement went differently for the Rochester Franciscans and the land surrounding their Assisi Heights motherhouse.

In fact, it started somewhere else.

Around 2013, the congregation began discussions about ways to preserve the land at their Holy Spirit Retreat Center in Janesville, Minnesota, 70 miles west of Rochester. They first reached out to the Minnesota Land Trust, with which they had worked in the past.

At the time, the trust had a two-year process for acceptance, which included studies of the land to determine its appropriateness for preservation. Attached to that was a $20,000 application cost. The sisters explored grant opportunities to help cover the costs, with no success.

As they explored other options, they began discussions with Waseca County, which oversaw conservation easements. In July 2017, they received approval from the county to place 19 of the 34 acres at the retreat center into an easement, including four acres near its center, which are to remain untouched wilderness.

Map of the Sisters of St. Francis motherhouse, Assisi Heights and the conservation easement (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Francis)

Sr. Jennifer Corbett, who served as a hermitage caretaker at the retreat center, said the feeling of holiness exuding from the land led them to pursue the easement.

"I think it was an impetus to carry on the sense that this is a holy place," she said.

The process with the Holy Spirit Retreat Center, which the sisters sold in 2018, paved the way for the Rochester Franciscans to consider possible conservation options at Assisi Heights after a committee of sisters proposed forming a task force to pursue an easement there.

Unlike Waseca County, Olmstead County, where the motherhouse is located, didn't offer easements. Rather than revisit the Minnesota Land Trust or another conservation group, such as Ducks Unlimited, the sisters decided to create their own foundation to oversee the easement.

A foundation would give the sisters more control over determining what they wanted the easement to be, said Sr. Ramona Miller, president and congregational minister.

The sisters reached out to their longtime lawyer, who brought in a top real estate lawyer to help them navigate the paperwork. Along with the land, the Rochester Franciscans wanted to also protect the animals living there.

"It's not just about preserving the green space, the fresh air, the look of it, but really preserve the habitat for animals," said Sr. Charlotte Hesby, who served as caretaker at Holy Spirit Retreat Center for two decades and was involved in both easement decisions.

But the real estate lawyer told them that animals were not considered real property under the law. To work around that, the sisters wrote into the easement that "the Green Space be maintained and preserved as an example of the Franciscan care for nature and a home for animals and birds."

On July 18, 2019, the Rochester Franciscans held a prayer service in their Lourdes Chapel where they announced the easement had been established.

A proclamation read by Miller at the service stated that "this property will serve as a lasting reminder of the many significant charitable and cultural contributions made by members of the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Francis, and that this Green Space shall be maintained as a natural resource, a place of quietude and suitable habitat for a wide variety of plants, animals and birds, in perpetuity."

Looking back, Corbett said now takes a more urgent view of the easement, as signs of climate change and environmental destruction become more apparent. It's much clearer to her not only how congregations like theirs can take steps to preserve creation, but why it's a natural fit.

"It's part of our mission, it's part of how we understand ourselves," she said.

Editor's note: The Sisters of St. Francis of Rochester have donated to the Laudato Si' Fund, which was established to help endow NCR's coverage of the climate crisis. Reporting for this series was made possible, in part, by the Solutions Journalism Network.