A banner for the People Not Pozos campaign hangs on the front of the Alegria Apartments in June 2013, across the street from the AllenCo Energy oil production facility in Los Angeles. The campaign has sought the permanent decommission of the facility's oil wells due to adverse health issues the neighborhood experienced before operations ceased in 2013. (Esperanza Community Housing)

An oil drilling facility in a south-central Los Angeles neighborhood is on the verge of being permanently shut down, potentially representing a long-sought victory for residents but one with virtually no assistance from the local archdiocese, which owns and leases the land.

For a decade, the predominantly Hispanic community of University Park has fought to close the AllenCo Energy oil drill site on 23rd Street, just blocks from Mount St. Mary's University and a mile north of the University of Southern California. Shortly after operations began in 2009, the neighborhood complained of a series of health ailments, which persisted until production was suspended in 2013 following numerous health and environmental violations.

The community, relieved that operations halted, still feared they could restart at some point and have lobbied both the city and Los Angeles Archdiocese, which owns the property, to block a return of operations and the accompanying illness-inducing pollution.

On March 5, their prayers appeared answered.

Advertisement

The California Department of Conservation ordered the permanent closure of the AllenCo Energy site and its 21 wells sealed. But two weeks later, on March 18, AllenCo exercised its right to appeal the decision. With state stay-at-home orders in place because of the coronavirus pandemic, no hearing date for the appeal has been set, the department told EarthBeat. That has put any celebration among the University Park neighborhood on hold.

"They're in a good place, knowing that resolution is around the corner," said Hugo Garcia, campaign coordinator for environmental justice with Esperanza Community Housing, one of the main organizers of the People Not Pozos ("People Not Wells") campaign that sought the AllenCo site's decommission. "But at the same time, until they get it in black and white that they're shut down, that it's final, there's still that stress and pressure that they're undergoing. That continues."

When the Department of Conservation issued its order, Esperanza Community Housing called the decision a "victory for community health." Executive Director Nancy Halpern Ibrahim added in a statement that the stand against the AllenCo Energy oil wells, as well as others across L.A., are encouraging signs of progress to prioritize the well-being of communities over oil and gas operations.

"This is about environmental justice," she said. "And, environmental justice is about racial justice."

Operations at the AllenCo Energy oil drilling facility, which began in 2009, were voluntarily suspended in November 2013 after numerous health and safety violations. People in the surrounding area, with some houses just 30 feet from the drilling site, complained of recurring nausea, nosebleeds, migraines, asthma and other respiratory ailments that they attributed to the facility's odorous fumes and chemicals. Hundreds of complaints were filed, and investigations by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and state air quality regulators levied hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines on AllenCo for health, air and water pollution violations. The L.A. petroleum administrator told NCR in 2017 AllenCo was "probably the worst example" of an oil operator in a city with more urban oil wells than anywhere in the country.

The penalties, while welcomed by the neighborhood, did not fully close the door on a future resumption of drilling operations. In 2015, AllenCo Energy received an operating permit outlining a series of compliance steps to complete before it could reopen. The Department of Conservation order in March noted gas leaks were found during inspections in the fall. Since the order, another seven minor gas leaks were discovered at the site, all of which have since been addressed.

AllenCo Energy declined to comment for this story.

The AllenCo Energy facility is leased on land the archdiocese received in the early 1950s as a gift from the family of oil baron Edward Doheny. It also owns and leases the land at another nearby oil drilling site that remains active.

At various points in their efforts to close the AllenCo facility, community advocates in the low-income University Park neighborhood have appealed for intervention by the Los Angeles Archdiocese and Archbishop Jose Gomez, who last year became the first Hispanic bishop elected president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Those calls were repeatedly ignored, they said.

In January 2014, Allis Druffel, Southern California outreach director for California Interfaith Power & Light, wrote to Gomez asking him to examine the situation and end the lease. That month, the city filed a civil enforcement action against AllenCo.

"It was a wasted opportunity," she told EarthBeat in an email. "The Archdiocese could have said something like, 'We understand this issue, and for the sake of public health and the Catholic Church's commitment to the protection of life we are working to resolve this issue.' "

Druffel, a former chair of the Peace and Justice Commission and its Creation Care Ministry before both were rolled into the Office of Life, Justice and Peace, said she also reached out to other Catholic leaders and decision-makers asking for their assistance with the campaign. Among the archdiocesan employees she spoke to at the time, few knew about AllenCo, much less that it and the other drill site operated on archdiocesan property.

The Los Angeles Archdiocese did not answer specific questions from EarthBeat about its oil properties or its relationship with the University Park community. In a statement, it said "The health and well-being of our communities are always a priority for the Archdiocese. That is why the Archdiocese continues to cooperate and work with the City and AllenCo to find an alternative use for the site that is in the best interest of the community and all other stakeholders."

The archdiocese added it has supported environmental regulators in their work to ensure the AllenCo facility operated in accordance with all public safety and air quality requirements, and that it "is in continued communication with the respective organizations involved in the hopes of finding a just resolution that ensures that the health and well-being of the surrounding communities are protected and prioritized."

Along with residential homes and college campuses, the AllenCo Energy site is adjacent to a school for special needs children and several churches, including St. Vincent de Paul Parish. It was during her time as a community organizer for the parish that Social Service Sr. Diane Donoghue formed Esperanza Community Housing in 1989 as part of her advocacy for affordable housing.

Members of Esperanza Community Housing made numerous attempts to meet with the archdiocese about the AllenCo site in recent years. Outreach to Mount St. Mary's and St. Vincent, located across the street from Esperanza's offices, has yielded varying levels of success.

The women's university hosted several early community meetings and sits in on monthly calls. People on campus also experienced health issues while AllenCo was drilling. Debbie Ream, a university spokesperson, said the school continues to monitor the facility's status and the campaign to close it.

"We support our neighbors," she said, adding she was unaware of any conversations about AllenCo between the archdiocese and Mount St. Mary's, which was founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph.

As for St. Vincent Parish, Garcia said he made repeated calls requesting a meeting, including close to two dozen in 2018 as part of a broader outreach to faith communities, but none were returned. Fr. David Nations, pastor at St. Vincent, declined to comment and directed questions to the archdiocese.

"The archdiocese has continued to choose not to have any dialogue with the community, and not because we don't want to," Garcia told EarthBeat.

The image of a Catholic archdiocese facilitating oil drilling at the detriment of a local community stands in contrast to church teachings on stewardship of the environment, elevated all the more under Pope Francis. Throughout his papacy, Francis has spoken out strongly — and at times, delivering the message directly to top oil executives — on the need to transition the global economy away from fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas. Such a shift is necessary, the pope has said, not only to limit climate change but to protect marginalized communities from health and justice issues that can come with mining and drilling.

"Some forms of pollution are part of people's daily experience. Exposure to atmospheric pollutants produces a broad spectrum of health hazards, especially for the poor, and causes millions of premature deaths," the pope wrote in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," which will mark its fifth anniversary this month.

Last year, the California Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a sweeping pastoral statement signed by all the state's bishops, including Gomez, outlining how the church will implement Laudato Si' in the Golden State. In it, the bishops pledged to pursue renewable energy and energy efficiency measures in their institutions and explore "opportunities for divestment from fossil fuels, whether through Diocese bank investments, oil leases, etc."

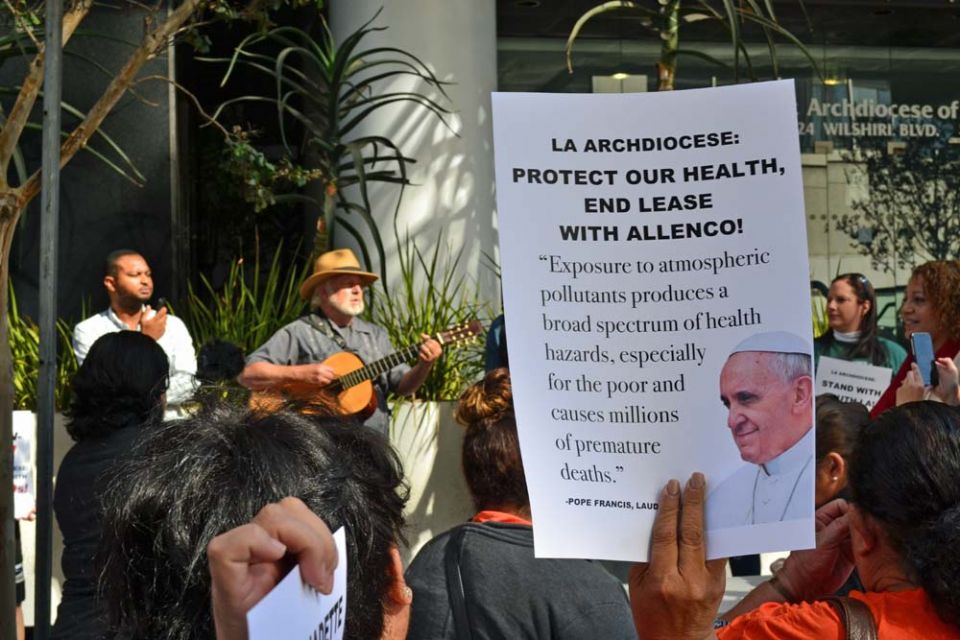

In October 2017, advocates for the University Park neighborhood staged a rally outside the archdiocesan headquarters, complete with signs quoting passages from Laudato Si', asking Gomez to get involved and prevent any future drilling at the AllenCo site.

A demonstrator holds up a sign with a passage from Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" during a protest Oct. 4, 2017, outside the chancery of the Los Angeles Archdiocese. Approximately 50 people attended the demonstration, urging the archdiocese to cancel a land lease agreement allowing oil drilling within a south LA neighborhood. (STAND-LA)

At the time, the archdiocese downplayed its role, then telling NCR in a statement it "is not directly involved in the permitting process and does not operate the site." The archdiocese added it was working with AllenCo and city officials on alternative uses for the site.

The Los Angeles Times reported in March that the archdiocese has engaged in talks with AllenCo about ending its business ties with the site. It also reported that city officials planned to discuss with the archdiocese alternative uses for the land, such as a park or affordable housing.

On at least two occasions, the neighborhood has appealed directly to the pope. In one video, posted in January 2014, Nalleli Cobo, a student at St. Vincent de Paul School, described the nosebleeds and headaches she has experienced, and asked Francis for his help to shut down the oil wells near her home forever.

"Through a lot of hard work, our community has managed to shut down the oil plant temporarily. However, every day I'm afraid that they will reopen and we will again be exposed to their toxic emissions. This is the reason why I'm reaching out to you: We need your help in making sure it shuts down permanently," she said.

Garcia was explicit that the People Not Pozos campaign is not anti-Catholic, and has avoided any messaging that could be construed that way, careful not to alienate a large portion of residents who are Catholic or Christian. Instead, the group has focused the oil site's closure squarely as a public health issue. With that, they have highlighted how some of the chemicals from the facility can harm reproductive health in a neighborhood where roughly a quarter of the women are of childbearing age.

Studies have found living close to oil wells can put people at higher risk of numerous adverse health effects, including cancer and congenital heart defects in infants.

According to STAND-LA, a grassroots organization that opposes neighborhood drilling, 759 of the 1,071 active oil wells in Los Angeles are within 1,500 feet of homes, schools, churches and hospitals. A separate report released in April from FracTracker Alliance, a non-profit that investigates the health effects of oil and gas development, found 215,000 LA.. residents live less than a half mile from one of the state's nearly 106,000 active oil or gas wells. Statewide, that's the case for 860,000 Californians, with 40% of residents (55% in L.A.) of Hispanic heritage.

STAND-L.A. and Esperanza Community Housing have advocated for L.A. and the state to establish a 2,500-foot buffer zone between residential areas and oil wells. (That's less than a half-mile, which is 2,640 feet.)

While the archdiocese has been largely silent, other faith communities have stepped up. Ministerios Manantial De Amor, a Baptist church blocks away from AllenCo, has supported the People Not Pozos campaign, inviting Garcia to speak and share information at its services. One of its pastors spoke at a September 2018 demonstration in front of AllenCo.

Earlier this month, California Interfaith Power & Light sent congratulations to Esperanza Community Housing from its members across the state and across denominations. Druffel told EarthBeat they wanted to recognize the community's long fight, and in the midst of the pandemic, celebrate some good news, too.

"We need to know that Goliath does not always win and that the power of community, cooperation among many organizations, and the voice of the people raised to decision-makers all make THE defining difference in social and climate justice," Druffel, the former chairperson of the archdiocese's now-defunct Creation Sustainability Ministry, said in an email.

Asked what he would say to Gomez if given the chance, Garcia said he would ask the archbishop to use his leadership to do everything in his power to revoke the lease from AllenCo Energy, prevent any future drilling on the site and repurpose it in a way that benefits the community.

"I would say that the community would greatly appreciate the archdiocese demonstrating their faith and their commitment to parishioners, many of which have suffered the ill effects of AllenCo and oil drilling operations," he said.

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]