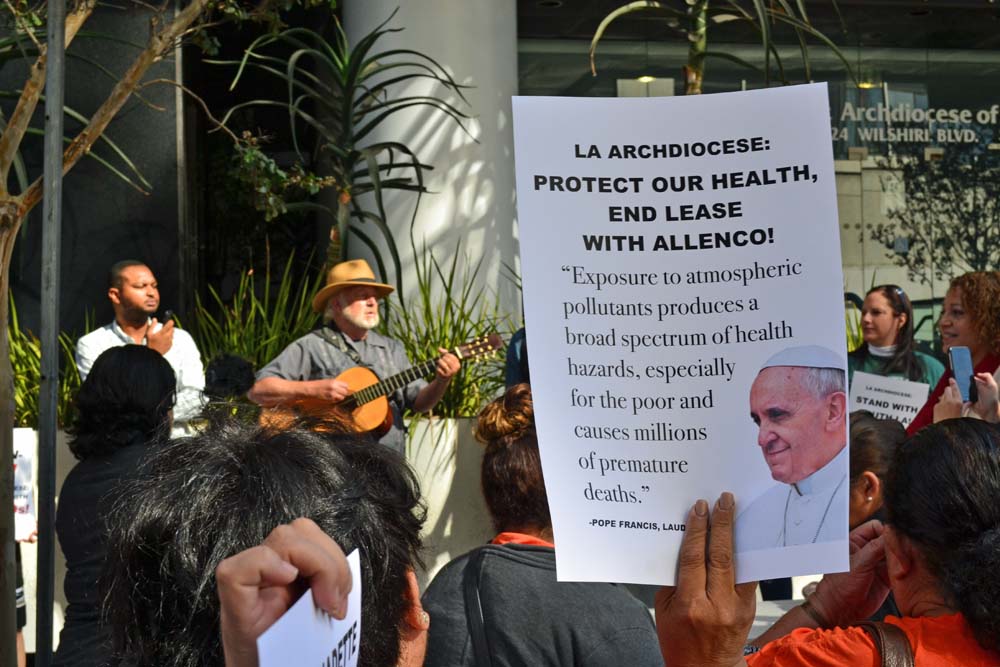

A demonstrator holds up a sign with a passage from Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" during a protest Oct. 4 outside the chancery of the Los Angeles Archdiocese. Approximately 50 people attended the demonstration, urging the archdiocese to cancel a land lease agreement allowing oil drilling within a south LA neighborhood. (STAND-L.A.)

The potential reboot of operations at a dormant oil facility leased on land owned by the Los Angeles Archdiocese has sparked new concern among neighbors of the well who fear a restart in drilling will resurface health issues they hoped were in the past.

Since fall 2013, the oil facility operated by AllenCo Energy Inc. in the University Park neighborhood in south-central Los Angeles has sat idle following a bevy of health and safety violations and fines issued by multiple regulatory agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Years before, residents of the largely immigrant and low-income neighborhood had complained of the smell coming from the site — situated 30 feet from homes, and on two acres of land owned by the archdiocese, which received it as a gift in the 1950s from descendants of oil baron Edward Doheny. They reported instances of nausea, migraines and nosebleeds, as well as new cases of asthma they attributed to noxious fumes emitted from the facility.

With word circulating this summer that a restart in operations could come soon, the neighborhood and its supporters have mobilized to preemptively urge the Los Angeles Archdiocese to terminate its lease agreement with AllenCo and prevent any future drilling on the site.

"We wish that they would really see that it's their land, and they have the power to cease [the drilling]," Gabriela Garcia, whose family has lived in University Park for four decades, told NCR.

Garcia, 35, joined approximately 50 fellow residents and supporters Oct. 4 in a protest outside the Archdiocesan Catholic Center. She and neighbors shared their experiences from when the urban oil well was in operation — in addition to bouts of nausea and respiratory ailments, one young girl went to the hospital with heart palpitations — and how since it's been inactive, they've been able to breathe more freely.

"We are worried that if AllenCo reopens, we will go back to a lifestyle of keeping our windows shut every day, not being able to take a walk outside," Alicia Escamilla, who has lived in the neighborhood since 2012, said at the protest. "We don't want to be a sick community again."

The protest was organized by Stand Together Against Neighborhood Drilling-Los Angeles, or STAND-L.A. Some people held signs with a picture of St. Bernadette of Lourdes, who suffered from extreme asthma as a child, while other signs highlighted passages from Pope Francis' encyclical on the environment "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." Sections of the encyclical were also read during the demonstration.

Martha Argüello, co-chair of STAND-L.A. and executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility, addresses a demonstration Oct. 4 outside the Los Angeles Archdiocese chancery against a possible restart in oil drilling operations on land leased by the archdiocese within a south LA neighborhood. (STAND-L.A.)

"Some forms of pollution are part of people's daily experience," Francis wrote early on in the document. "Exposure to atmospheric pollutants produces a broad spectrum of health hazards, especially for the poor, and causes millions of premature deaths."

Organizers said they held the protest after multiple requests to meet with the archdiocese went unanswered. That included three letters, two sent in June and another in August, addressed to Archbishop Jose Gomez; copies were also delivered to the Office of Real Estate, the Office of Life, Justice and Peace, and the director of government and community relations.

In a statement, the Los Angeles archdiocese said it "is not directly involved in the permitting process and does not operate the site," adding that to its knowledge AllenCo is still in the process of complying with regulations and obtaining permits necessary before it can restart operations.

The archdiocese, which leases land at another oil site three miles west, said it is working with AllenCo, the Los Angeles mayor's office and other city officials "to explore alternative uses for the site in our continued commitment to the health and well-being of the entire community."

Uduak-Joe Ntuk, petroleum administrator for the city of Los Angeles, confirmed those discussions, describing them as "very preliminary." He said the site's "prime" location — sandwiched within a mile each of downtown to the north and the University of Southern California to the south — presents an opportunity for development beyond oil and gas exploration should the archdiocese decide to repurpose the land.

"It'd be different, I guess, if it was out in the desert somewhere," Ntuk said.

The petroleum administrator, appointed to the position a year ago after the city went 30 years with the office vacant, told NCR he has received dozens of phone calls in recent weeks from residents concerned about AllenCo restarting the drilling.

In July, Ntuk advised AllenCo against a possible open house in the works since the facility still lacked a fire suppression system approved by the Los Angeles Fire Department. The open house was eventually cancelled.

As far as AllenCo complying with its regulatory requirements, "they still have quite a ways ago," Ntuk said, estimating their progress below 50 percent.

The Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) of the California Department of Conservation told NCR the company still has a number of outstanding noncompliance issues among the 18 required actions it issued in April 2014, including the submission of mechanical integrity tests on nine idle wells and three underground injection wells.

DOGGR has not been notified of a potential resumption in operations, Don Drysdale of the public affairs office of the Department of Conservation told NCR. He added that AllenCo has reportedly been planning a meeting to discuss its air quality monitoring system, though no date has been set. Should that meeting occur, it would likely include regulatory bodies with oversight of the facility, as well as the city of Los Angeles and the fire department, Drysdale said.

The EPA said it has not received certification from AllenCo that it has completed all facility safety measures required under a 2014 order. That order also stipulates the company must provide notice it has completed the measures at least 15 days prior to reopening.

AllenCo did not respond to a request for comment.

The vast number of violations the company has accumulated makes it stand out, Ntuk said, in a city with the nation's largest urban oil footprint — encompassing 1,200 active wells on 18 different oil fields, with roughly 150 addresses with active wells and 20 large drill sites similar in size to AllenCo. According to STAND-L.A., more than 700 of the wells are within 1,500 feet of homes, schools, churches and hospitals.

"The vast majority of operators are willing to meet and have inspections. AllenCo is an outlier and probably the worst example we have in the city," Ntuk said.

Garcia remembers the conversations among neighbors shortly after AllenCo began operations in 2009, which quickly ramped up production by 400 percent in its first year, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Bumping into each other along the street, they asked one another "Do you smell something?" or "Did you feel that vibration in the ground?" The odor became so strong that residents avoided 23rd Street, the primary thoroughfare of the neighborhood and where the oil facility is located, during parts of the day when drilling took place. Attempts by AllenCo to mask the fumes with fruity scents didn't help.

Eventually, they began to organize, among themselves along with local faith groups and other community organizations, after their stories expanded to their children suffering nosebleeds, nausea, dizziness and migraines.

"All these common issues that were recurring with a majority of the neighbors," said Garcia, her own daughter awaking at times with blood on her pillowcase.

The residents filed hundreds of complaints to different regulatory agencies, including the EPA.

During an October 2013 visit to the AllenCo facility, EPA inspectors, including the regional administrator, became sick with sore throats, coughing and severe headaches. Two weeks later, U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., called for AllenCo to suspend its operations while EPA conducted its investigation, which the company voluntarily did.

During EPA's four-month investigation, the health issues in question disappeared among residents, the Times reported in July 2014. That month, the agency fined AllenCo $99,000 for violating federal environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, and had the oil company agree to $700,000 in "significant improvements" required by EPA.

AllenCo was also later ordered to pay $215,750 in penalties by the South Coast Air Quality Management District for 18 air pollution violations. Among them, creating odors causing a public nuisance and improperly controlling emissions from a wastewater tank and other equipment that released smog-forming compounds into the air. In May 2015, the regional air quality regulator issued the company a revised operating permit that included 17 conditions to be met before it could reopen, in addition to complying with other oversight agencies' requirements.

In June 2016, Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer secured a court-ordered permanent injunction against AllenCo that carried $1.25 million in civil penalties. The injunction required AllenCo to comply with all local, state and federal health and safety regulations, in addition to addressing all violations, and to install an environmental safety monitoring system.

Advertisement

Even with enforcement measures in place, residents worry about a possible restart. Two years after operations halted, they appealed to the pope in a video, sent a month after he issued Laudato Si', asking Francis to intervene and request the archbishop to prevent future drilling as a way of putting the environmental encyclical into action.

The potential for AllenCo to restart drilling "hangs over our minds," Garcia said, and motivates them to make a "moral call" for the Los Angeles archdiocese to end it. The community considers itself not opponents, but rather a part of the church, she added, with many attending St. Vincent Catholic Church, itself just blocks away from the AllenCo facility. The Doheny campus of Mount Saint Mary's University is also nearby.

"[The archdiocese is] an extension of our current community, so they should be responding to our concerns, the real concerns of what's the impact of something that's happening on their land," Garcia said.

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]