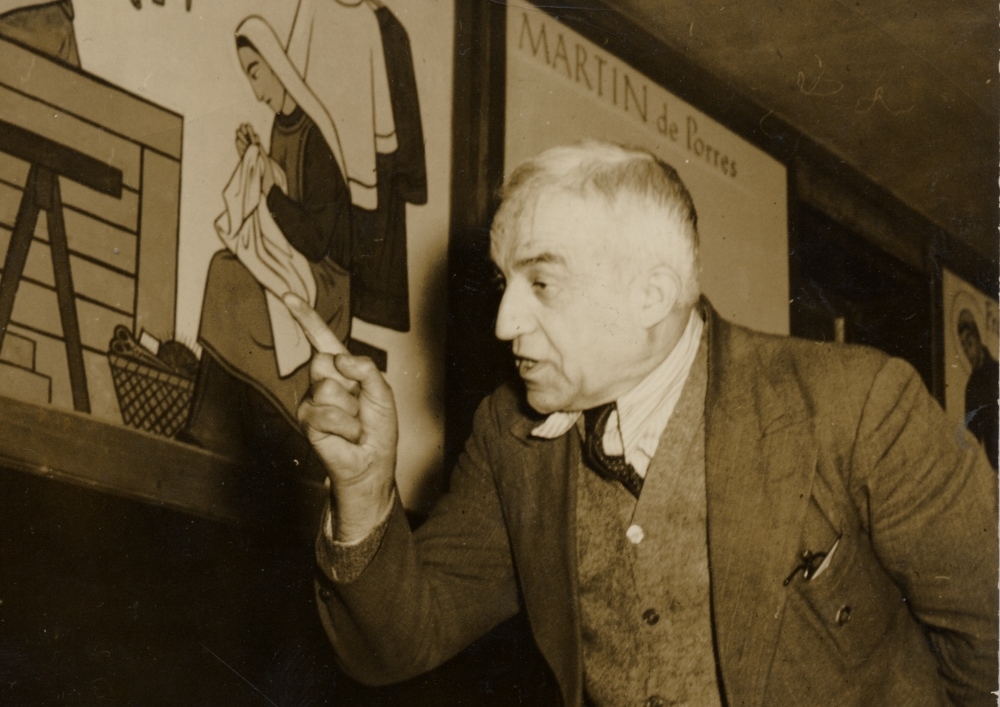

Catholic Worker co-founder Peter Maurin at St. Isidore's Farm in Aitkin, Minnesota, in 1941 (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries/Photo by Mary Humphrey)

"He asked nothing for himself, so he got nothing," Dorothy Day wrote in Loaves and Fishes of Peter Maurin, the man she considered the true founder of the Catholic Worker movement.

Maurin did not cling to possessions, demand respect or seek personal recognition. He often takes a backseat to Day in stories of the movement they co-founded, and the aspect of the Catholic Worker that he's most associated with — farming communes or "agronomic universities" — was for decades considered one of the movement's biggest failures.

However, in his very poverty and meekness, Maurin found his vocation: as a disciple of Christ on a mission to transform the modern world — in his own words — "from a society of go-getters to a society of go-givers."

Now, 70 years after his death, Maurin's vision of a constructive program to reshape society through a synthesis of "cult, culture and cultivation" is gaining traction as it resonates with modern ecological and societal concerns.

Maurin "presented a vision of farming communities that honored mind, body and spirit," said Eric Anglada, who felt burnt out after living in an urban Catholic Worker and joined St. Isidore Catholic Worker Farm in Cuba City, Wisconsin. "He insisted that all three needed to be nourished in order to find health, and that a truly healthy culture needed to have what he called a proper regard for the soil."

Maurin was born May 9, 1877, in Oultet, France, the first child of a large farming family. Educated by the Christian Brothers, Maurin joined the order for several years, leaving before he took final vows.

As a young man, he lived in Canada and then the U.S., working at various times as a homesteader, traveling laborer and French teacher. He read extensively and began to develop the ideas that would inspire the Catholic Worker movement.

Maurin decided that modern society had failed and it was time to "build a new society in the shell of the old." This would happen through a "green revolution": a return to life on the land that would synthesize cult (religion), culture (learning and arts), and cultivation (agriculture).

While he outlined a three-point program of action — roundtable discussions for "the clarification of thought," houses of hospitality where the works of mercy could be practiced, and founding farming communes or "agronomic universities" — Maurin needed help to implement his vision. In 1932, he sought out Day, a journalist and Catholic convert living in New York City.

Peter Maurin in the 1930s (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries)

While Day understood and supported Maurin's message, she also brought her own ideas and expertise. When Maurin convinced Day to start a newspaper to spread his ideas, he imagined it would consist of nothing but his own "Easy Essays," short poetic compositions written in blank verse, meant to be read aloud, and filled with repetition and plays on words to catch people's attention and be accessible to all.

But the first edition was filled with Day's articles on the oppression of workers, as well as his essays. Maurin was disappointed and walked out the room, not to return for some time. He eventually accepted the paper's format, removed himself as editor, but continued to include his essays weekly.

Day's leadership helped advance many practices and philosophies that Maurin promoted, such as voluntary poverty, personalism (a philosophy that emphasizes the freedom and dignity of each individual and the need to take personal responsibility for others' needs) and a decentralized society.

While The Catholic Worker newspaper had originally called for the church to establish houses of hospitality, readers' confusion and Day and Maurin's generosity made Day's apartment a hub for those in need of a meal or a cup of coffee. Before long, they were renting a larger space to care for people, and then a whole building.

Similar houses sprung up in other cities, inspired by the New York house. They were staffed by volunteers who lived in community with each other and with the homeless or impoverished guests who came to them for help. Discussions for clarification of thought were also organized early on, and a farming commune eventually followed.

Maurin remained a central figure in the movement, even though Day's approach, rooted in her urban background and her experience with journalism, protests and activism for issues such as workers' rights, differed from Maurin's.

Peter Maurin speaks at a retreat at the Catholic Worker Maryfarm in Easton, Pennsylvania, in September 1940. (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries)

Day supported striking workers, for example, but Maurin's refrains were "strikes don't strike me" and "work not wages," said Brian Terrell, a longtime Catholic Worker who originally joined the movement and worked with Day in New York, but currently lives at Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker Farm in Maloy, Iowa.

"He had a more radical idea that rather than fighting for a decent hourly wage, that people should be struggling for a world where no one is working for money in the first place," Terrell said.

And while Day originally framed the founding of a Catholic Worker farm as a shift in focus to the country, with some activities continuing in the city, "she presents the farm in her last years not as the cutting edge of the Catholic Worker revolution, but as an auxiliary, a place where city people go to rest" or obtain food, Terrell said.

Day's differences with Maurin were both a necessary counterbalance to his less practical, more idealistic bent, and a more accessible introduction for those not yet familiar with the movement, several Catholic Worker farmers suggested.

Maurin's emphasis, which various Catholic Workers described as "deeper," "constructive" and "holistic," can take longer to appreciate. But for some who have spent years in the movement, his vision has become more attractive.

"Farming is not flashy," said Chris Montesano, who was initially drawn to the farming aspect of the Catholic Worker but spent time in city houses in New York and San Francisco before founding Earth Abides Catholic Worker Farm in Sheep Ranch, California, in 1976, when few Catholic Workers were interested in farming.

Brian Terrell and goats at Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker Farm in Maloy, Iowa (Betsy Keenan)

While people are more drawn to protests, Montesano believes that farming is "the most fundamental form of resistance to this society that currently exists," because growing one's own food and building community is a way to partially withdraw from the capitalist system "in a way that is constructive."

Day's message of feeding the hungry and protesting injustice is "very accessible to an American young person," said Terrell, but it took years before he "saw the attraction" in Maurin's philosophy, "because it's just deeper."

"Without a reflection on why people are hungry and without thinking about solutions or changing society, it's treating the symptoms but not the disease," he added. "As you stay longer, you get to see that a soup line is not enough."

Terrell, who is also a co-coordinator with Voices for Creative Nonviolence and spends a considerable portion of his time traveling to participate in advocacy and protests for peace, described the farm as a way of preparing for "when peace breaks out" and people can no longer rely on economic relationships based on violence or exploitation to meet their needs.

"We do need to go to demonstrations and sit in at congresspeople's offices and blockade weapons factories and things like that, but we also have to realize that our prosperity is built on war and we need to find alternatives," said Terrell. The goal is "to try to find economic relationships that are fair and that are not exploiting other people and not hurting the Earth."

Anglada agreed.

"The Catholic Worker is really meant to be building a new society in the shell of the old and I think we can do that the best on the land and actually providing for some of our own needs, at least, and providing an alternative to consumer capitalism," he said. "Urban communities still, in many ways, live off of the waste and refuse of the urban industrial system and the farms are really, I think, where actually creating an alternative can happen."

Advertisement

That alternative, several Catholic Workers emphasized, isn't just about living in a more environmentally sustainable way, but about fostering healthy spirituality and community rather than the selfish and acquisitive individualism that they see as the root of our current ecological and societal issues.

Maurin wrote in one of his Easy Essays that the goal was:

to foster a society

based on creed

instead of greed,

on systematic unselfishness

instead of systematic selfishness,

on gentle personalism

instead of rugged individualism.

At Peter Maurin Farm in rural Queensland, Australia, founders Jim Dowling and Anne Rampa* stressed the importance of voluntary poverty on both a spiritual and environmental level.

Day once said that Maurin's dedication to voluntary poverty was so extreme that perhaps the only possession he really valued was his mind. (He eventually surrendered that as well, experiencing an apparent stroke that made him lose his ability to think clearly several years before his death.) When Maurin died May 15, 1949, he was buried in a donated grave, wearing a donated suit.

Dowling called Maurin's emphasis on voluntary poverty "the most important thing in this day and age, where Western so-called civilization and probably most of the world" have been overwhelmed by materialism. "The whole environmental crisis is one that's being caused by desire for more and more and more affluence and things."

"Downward mobility, the simple life that Peter Maurin proposed," can solve both our spiritual and environmental crises, he added.

Decades after Maurin's death, that message is starting to seem more compelling. While in the past, Catholic Workers were skeptical of farmers within the movement, the farms are now widely accepted and most urban houses of hospitality try to incorporate a garden, Terrell said. He noted that he now often hears of new farms being started.

Anglada said that a recent Midwest Catholic Worker farmer gathering attracted about 75 people, similar to the number who attended a recent general Midwest Catholic Worker gathering. An online Catholic Worker directory currently lists 24 farms, including four outside the U.S.

While the movement is still small, Catholic Worker farms in Australia and New Zealand are increasing, and children of Catholic Workers are staying in the movement, Rampa said.

In California, the aging community members of Earth Abides have found a group of young people from Canticle Farm — an urban community in Oakland that cites Catholic Worker as among its inspirations — who are interested in taking over the farm, Montesano said.

At Earth Abides Catholic Worker Farm in Sheep Ranch, California, Mara Rosenhart teaches adults and children to dye alpaca wool at a Farm-To-Fiber craft workshop retreat in 2015. (Courtesy of Trinity Nuclear Abolition/Marc Page-Collonge)

People in modern U.S. society are "weak on" community and instead understand "rugged individualism," he added. "It's led us down this path, the industrial growth society, where we're destroying the planet," but people are beginning to realize "that the way we have been living our lives is not sustainable."

According to Montesano, growing concern about climate change has helped people see the prophetic nature of Maurin's view that industrialism was a blind alley "and the only thing you could do when you were walking down a blind alley was turn around and walk the other way."

In the past, some who have studied or belonged to the Catholic Worker movement, such as author Mel Piehl, suspected that Day exaggerated Maurin's role because having a male founder helped legitimate her movement. While there might be some truth in that, Terrell said, Maurin's stature as a true founder of the movement has been increasing as more people are inspired by his specific vision.

"If he wasn't the founder in 1933 ... years after his death he's grown into that role."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]

*An earlier version of this story misstated Rampa's last name