George Catlin, Medicine Buffalo of the Sioux, 1837-1839, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.485

Walking through the several small rooms that comprise the Smithsonian American Art Museum's exhibit "Picturing the American Buffalo: George Catlin and Modern Native American Artists" (through April 12), it's easy to empathize with the buffalo. Here a colorfully-attired Native American warrior on horseback is poised to drive a long spear through the back of a cowering buffalo (also called bison), and a nearby painting captures such detail that it can only be described as a personified portrait of a bloodied, dying buffalo.

The latter painting, Catlin's "Dying Buffalo, Shot with an Arrow" (1832-3) is not what it seems, though, and as such, it stands in as a microcosm for the larger exhibition. Catlin was among the first artists of European descent to venture beyond the Mississippi River, and he went on five extended expeditions between 1830 and 1836 to record the indigenous people's "manners of customs." He sought to humanize Native people in his paintings and in an exhibition that he created of his work, for which he would dress in Native clothing (which he collected among other artifacts associated with Native Americans) and perform some of the rituals he had observed. But he also romanticized the people he recorded and whom he thought were disappearing.

The dying buffalo painting, a museum label notifies visitors, demonstrates that Catlin wasn't thinking ecologically here, but was instead interested in depicting the operatic moment of this massive animal's death. Catlin wrote that he drew the buffalo in his sketchbook as it died. "He stood stiffened up, and swelling with awful vengeance, which was sublime for a picture," Catlin wrote, "sometimes he would lie down, and I would sketch him; then throw my cap at him, and rousing him on his legs, rally a new expression, and sketch him again."

Advertisement

Catlin brought the same cold distance to his portraits of indigenous people. "He is predicting the ultimate demise of Indians and Indian culture, and he is motivated by a romantic longing to... preserve some record," says David Penney, associate director of museum research and scholarship at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian. "Romanticism, pastoralism, nostalgia is all about things that are disappearing, things that are no longer accessible. And this becomes a huge theme or a trope in white regard for American Indians in North America."

The son of a devout Methodist mother and a philosopher father—"professing no particular creed, but keeping and teaching the commandments," he wrote—Catlin grew up hearing stories from his mother, Polly Sutton, and maternal grandmother, who were captured by Native Americans in the Battle of Wyoming in July 1778. His father fought in the battle as well, and after the two were released safely, the stories that they told the young Catlin were said to have sparked his interest in documenting Native Americans. (Catlin is also to be credited, some say, with pioneering the idea of national parks.)

Some of the work by 19th Century artist George Catlin on display as part of the “Picturing the American Buffalo” exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Menachem Wecker)

But Catlin also felt in the 1830s that he was to be the historian preserving record of the last generation of Native Americans, according to Penney. Nearly 100 years later, in the 1920s,

Edward Curtis set out to photograph American Indians for the same reason. "He was basically photographing the great-grandchildren of those predestined for disappearance from Catlin's point of view," Penney says. "Curtis was saying the same thing about them."

In the paintings on view in the exhibition, Catlin expressed particular interest in indigenous spiritual practices that often centered on buffalo. Human beings have hunted buffalo for many centuries with an appropriate balance, according to Penney. "Buffalo proliferated North America despite human predation," he said. "You might argue kind of in hindsight—I don't think anybody would have thought about it this way—that they're sort of conservation-conscious hunting."

Without modern weaponry and technology, it wasn't possible for people to hunt buffalo to extinction, even though people so depended on buffalo. Even as visitors will likely find themselves sympathizing with the hunted buffalo in the exhibit, they should understand the context around these hunts, as compared to later, more devastating ones, which left only hundreds of roaming buffalo in the country at the end of the 19th century, when there had been an estimated 30 to 60 million in the 1850s. Today, the American bison's status is "near threatened," the rung below "least concern," according to the Smithsonian National Zoo.

George Catlin, Back View of Mandan Village, Showing the Cemetery,1832, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.392

By the 1890s, "The U.S. government slaughtered many bison in an organized effort to destroy the livelihood of Plains Indians," the zoo adds, noting that bison have made a comeback, now numbering around 500,000 in the nation. But they remain "heavily dependent on conservation action for survival."

Buffalo evolved over time to be smaller and faster to evade human hunters, according to Penney, and it wasn't until railroads proliferated, and buffalo "wet" hides could be shipped to tanneries in the east part of the country or Europe that buffalo faced extinction. "Previously, Native women, known for their prowess in the craft, processed the hides in the field. This made it difficult to scale up production of hides."

In Catlin's 1832 painting "Shoo-de-gá-cha, The Smoke, Chief of the Tribe," which is in the exhibit, the artist captured the chief, who had told him "that the buffaloes which the Great Spirit had given them for food, and which formerly spread all over the green prairies, had all been killed or driven out by the approach of white men, who wanted their skins; that their country was now entirely destitute of game."

The connection between the spirit and buffalo surfaces often in the exhibit. A late 1830s painting shows totems, including one with a rare white buffalo skin which carried special significance. "Together these totems represented a powerful offering to the Great Spirit," a label notes. A portrait of "Wún-nes-tou, White Buffalo, an Aged Medicine Man" (1832) depicts a very special man indeed, who was not only a medicine-man but also one who was given the name of White Buffalo. He was "necessarily looked upon as 'Sir Oracle' of the nation," Catlin wrote.

George Catlin, Buffalo Cow, Grazing on the Prairie, 1832-1833, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.405

Quite a few works feature buffalo dances, including Catlin's "Buffalo Dance, Mandan" (1835-7), which Catlin depicted was a ritual that could last several weeks. Every Mandan man had to keep a buffalo mask near his bed, and when called upon, he had to do the buffalo dance when buffalo were scarce. Dancing went on until buffalo were seen near the village, and when one dancer became tired, he would symbolically drop to the ground and be "hunted" by a blunt arrow. Having essentially played a buffalo, the tired man would yield to a colleague, who would take over the dance.

More recently, Thomas Vigil's "Buffalo Dance—Six Dancers, Two Drummers" (c. 1920-5), also on view, depicts eight figures. Two play drums, while three mean wear buffalo masks and clothing decorated with black snakes. Three buffalo maidens wear particular dresses, which go over one shoulder. "The men symbolize both the hunter and the quarry, while the women persuade the buffalo to sacrifice themselves for the benefit of the tribe," a label notes.

And Awa Tsireh's watercolor and pencil work on paper, "January 23rd, Buffalo Deer Dance" (c. 1918), shows the sacred ceremony, held annually on Pueblo's feast day, Jan. 23. Dancers donning deer and buffalo headdresses move along a snowy landscape. The subject, the exhibit reveals, was among the artist's favorites for its public and social nature.

"At a time when the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs attempted to restrict Pueblo cultural and religious practices, the watercolors of Awa Tsireh and other Pueblo artists helped to affirm the importance of ceremonial dance and ritual to their cultural survival," a label notes.

Elsewhere in the show, artworks show hunters visiting an image of buffalo cut out into the prairie grass before the hunt, a "medicine buffalo"; a view of a Mandan cemetery, wherein human bodies are placed to rot on scaffolds (which look like basic gazebos) and then the skulls are placed in a circle around buffalo skulls and medicine poles; and a self-torture Sioux ceremony that Catlin witnessed, wherein those aspiring to be medicine men leaned against poles with buffalo skulls and had to look at the sun from sunrise to sunset while a cord pierced their chest muscles. Calling it a "heroic test of endurance," as the exhibit does, is an understatement.

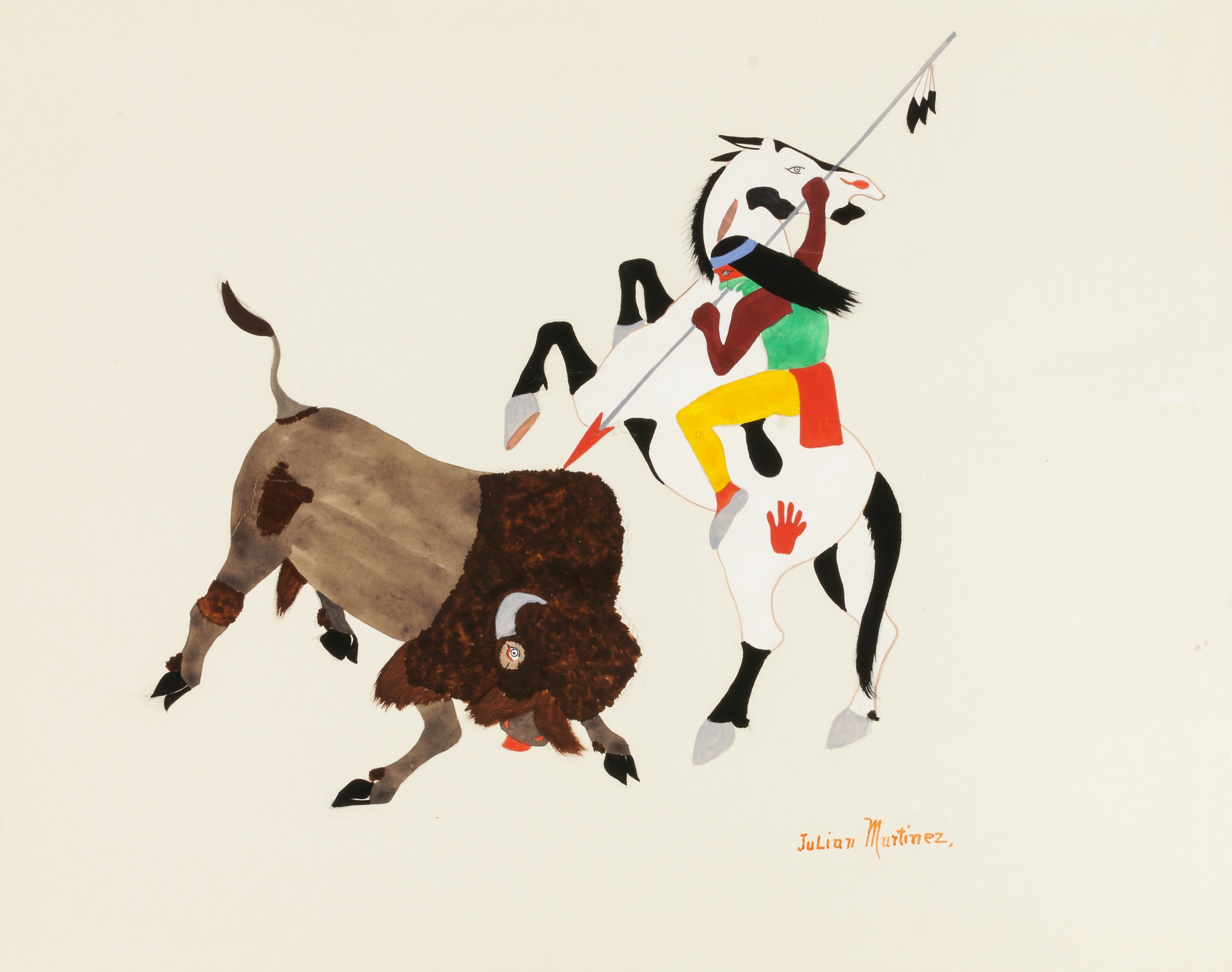

Julián Martínez (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Buffalo Hunter, ca. 1920-1925, watercolor, ink, and pencil on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Corbin-Henderson Collection, Gift of Alice H. Rossin*

One of the best examples of the connections between spirituality and buffalo might be a work that Penney cites, which isn't in the exhibit. A painting on muslin (fabric) attributed to Siyosapa, which was collected in the early 1880s at Fort Peck, Montana, shows in the bottom left corner, three hunters on horseback pursuing a herd of buffalo. The calves are portrayed in red, a sacred color. The image literally shows a Sun Dance and a prayer for success in battle, but Penney also thinks there's a prayer for the survival of buffalo.

"I am proposing that it may have been Siyosapa, the artist's wish to perpetuate the buffalo, which he certainly was aware were on the decline," he said.

*An incorrect caption was used with this painting in an earlier version of this review.

[Menachem Wecker is a freelance reporter based in Washington, D.C.]