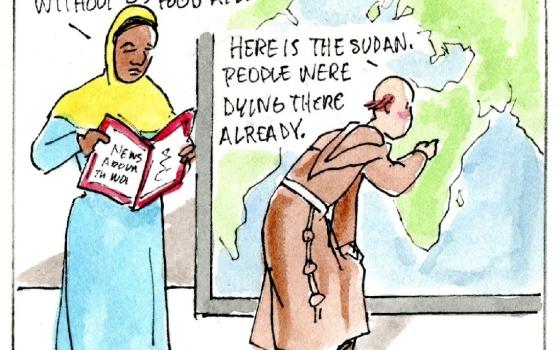

Girl Scout Julia Ocasio, 13, and Boy Scout Thomas Perotta, 10, use collection baskets during a Scout Sunday Mass Feb. 7 at Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in the Windsor Terrace neighborhood of the New York borough of Brooklyn. (CNS photo/Gregory A. Shemitz)

In New Jersey, Cardinal Joseph Tobin wants us to say no to "heartless" deportation policies. In Kansas, Archbishop Joseph Naumann wants us to say no to the Girl Scouts. And to the word "yoga."

Tobin joined an interfaith gathering of religious leaders May 4 in Newark, New Jersey, in a call to action against recent U.S. policy decisions that would have a direct effect on less-represented groups of people. Those acts include House passage of a bill to replace the current health care law and moves to accelerate deportation of people living in this country without legal documentation.

"What topples evil empires is the little person who goes into the square in the middle of town in the dark of the night and scrawls on the wall, 'No,' " Tobin said. "And I want to say to you, we are the No that God scrawls on the wall. We are the No to a nation who is heartless, who would deport people, separating them from their families and their loved ones simply because they are victims of a broken system."

A few days earlier, Naumann had instructed the pastors of his archdiocese to phase out their affiliation with the Girl Scouts of the United States of America and move their students instead toward the Christian-based group American Heritage Girls. His reason was a perception that the Girl Scouts are aligned with Planned Parenthood and groups that support the legal right to abortion. The national Girl Scouts organization has denied such an affiliation, but pro-life groups believe what they see. And what they see is Girl Scouts participating in the women's marches last January and references to feminist icons Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem in the 105-year-old organization's literature.

This comes on top of a decision by Naumann that classes at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas, that teach poses such as "downward-facing dog," "tree" and "cobra" should no longer use the term "yoga," because of its Hindu origins.

Can these two men be leaders of the same church? One implores us to encounter, to stand by the "other," to welcome the stranger. The other suggests a theology of fear — fear of outside forces and fear of change.

The stark difference in focus illustrates the cultural and political divide that is expanding within the church, especially in the United States. For some bishops, the fight has taken on the theme of church vs. the devil they view as the secular world.

The Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas, led by Naumann, draws that distinction on its website: "Secular schools and organizations operate from a secular worldview that is driven by opinion polls, fashion and trends," it states. "Catholics do not stop secular entities from espousing their ideologies in the public domain, but should we give them our children and the keys to our buildings?"

In Denver, Archbishop Samuel Aquila has said he will allow the Boy Scouts to continue operating in his diocese despite the group's decision to open the door to youths who identify as transgender, which he calls a "social experiment."

Disaffiliation with the Boy Scouts, he says, "would make a winner out of the secular culture and its agenda, and losers out of the Boy Scouts and the Church."

The message seems to be exceptionally simple: Secular — bad; sacred — good. What are we afraid of here? At what point did the entire non-church world become the church's target? What do these bishops accomplish by their sweeping denunciation of all things "secular"?

This latest phase of the culture wars hearkens back to the days of Pope John Paul II, which makes sense, given that many of these bishops formed their ecclesiology under his leadership. Let's not forget Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput's call last October for a "smaller, lighter church" that closes in around traditions and eschews the idea of inclusiveness and change from the world at large.

Of course, it was those larger forces that led Pope John XXIII to convene the Second Vatican Council to "recognize and understand the world in which we live" (Gaudium et Spes). We cannot separate Christian history from world history. Politics and trends, whether from the first century or the 21st, play a role in every Catholic's life, and to deny that would create a cloistered community that cannot expect to grow or thrive.

Compare the concept of small church to the message coming out of New Jersey, and, in fact, out of the offices of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops recently. The chairman of the bishops' Committee on Domestic Justice and Social Development is urging senators to rewrite the House health care bill to address "major defects" related to provisions for persons with low incomes, immigrants and those with pre-existing conditions.

Serious issues are at stake, and many in the church have taken the lead on finding a humane way to deal with the undocumented, to address gun violence or to resolve racial and income inequities. So when bishops such as Naumann or Aquila use their pulpits to wage war on the secular world, all they really do is distract from the true work of the church. Perhaps, because of atmospheric shifts under Pope Francis, that is a goal.

At NCR, we advocate for unified attention on the underserved, the poor and the stranger. We urge a deeper focus on encounters, which could also erase a need to inspire fear.