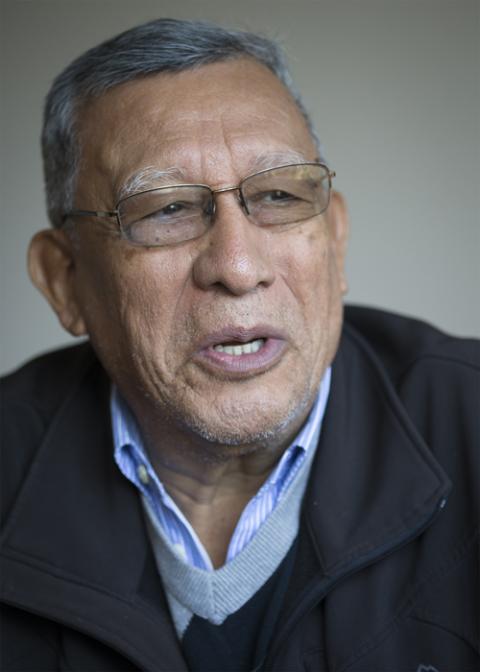

Fr. Estefan Turcios Carpaño, head of the human rights office for the Archdiocese of San Salvador, blesses a parishioner Dec. 30, 2018, after Mass at the Shrine of the Sacred Heart in Washington. (CNS/Rhina Guidos)

"Monseñor Romero is going to die," said Fr. Estefan Turcios Carpaño. "Although he has a wealth of help for us, if we don't do our part, inspired by him, Monseñor is finished."

San Salvador Archbishop Óscar Romero already died just over 39 years ago, assassinated March 24, 1980, while saying Mass. After his Oct. 14, 2018, canonization was much celebrated in his native El Salvador and encouraged the institutional church to embrace him, it seems unlikely that he'll be forgotten anytime soon.

But Turcios, a diocesan priest in Soyapango, El Salvador, who directs the human rights office for the Archdiocese of San Salvador, says Romero must be celebrated not only with "pretty words and slogans" but by continuing his legacy of engaging with lived reality and speaking out against injustice and violence.

He worries that El Salvador's current love for Romero will pass like a fleeting romance that ends in divorce or a broken engagement, "if we don't hurry to start creating structures that take Monseñor Romero as a light, but not only Monseñor Romero, that also take our reality, these problems that we're seeing, that we illuminate with Romero's words."

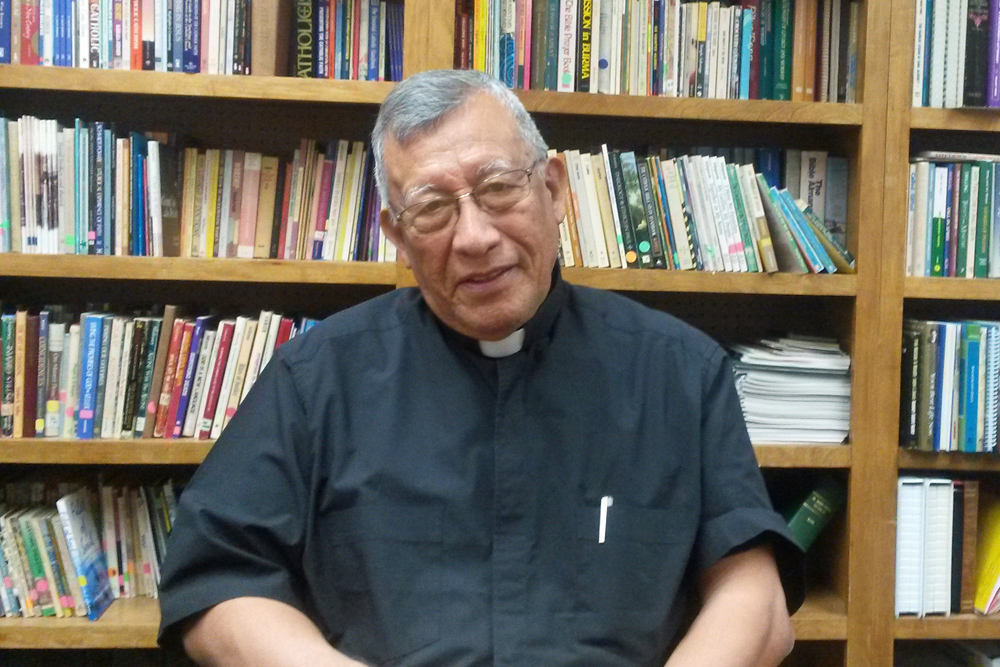

Fr. Estefan Turcios Carpaño, national director of the Pontifical Mission Societies in El Salvador and director for the human rights office for the Archdiocese of San Salvador is seen during an interview in Washington Dec. 27, 2018. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Unlike in Romero's time, El Salvador isn't engaged in a civil war between government forces and armed rebel groups, Turcios said. But he told NCR during an interview March 21 at St. Sabina Parish in Belton, Missouri, where he was visiting for the annual Romero celebration March 23, that his nation's current problems aren't so different.

Through his involvement with human rights and missions in his diocese, and his membership in the Municipal Council of Security and Citizen Coexistence of Soyapango, Turcios knows a lot about the situation in his country and his church — he called his interview with NCR on the subject, which lasted nearly two hours, just a "general panorama."

He also knows Romero. Turcios served as vicar of the Mons. Romero Foundation, and was personally acquainted with Romero during Turcios' time as a seminarian at San José de la Montaña in 1968 and after Romero was made archbishop in 1977.

Turcios says that while he was in jail for several months in 1977 due to government persecution of the church, Romero mentioned him in one of his homilies. After Turcios was released, but started seeing his name on lists of people who should be killed, Romero sent him to study in Ecuador for several years to protect him from further violence or imprisonment.

People participate in a March 23, procession to commemorate the 39th anniversary of the murder of St. Óscar Romero in San Salvador, El Salvador. (CNS/Jose Cabezas, Reuters)

The days of government persecution of clergy and others who tried to organize in support of human rights and economic justice are over, but Turcios says the underlying economic inequality has, if anything, gotten worse, and still spurs rampant violence, this time related to gangs.

"Before, the working class fought for better salaries, better social conditions, loans," Turcios said. Today, the unemployment rate is so high that people want work of any sort, even if it pays badly, yet still can't find jobs.

Many people engage in what Turcios calls "informal" work, selling items on the streets. Those who do have formal jobs don't earn a lot. Even after significant increases in recent years, the minimum wage ranges from $224.10 to $300 a month, depending on industry, according to the Fair Labor Association.

Turcios said even doctors, lawyers and engineers resort to other jobs, such as driving taxis, to make ends meet.

"The professional has been misled that if he studies he'll have a future," Turcios said, but many decide that migrating is a better option even though "here [in the U.S.] they don't practice medicine, but work in the hospital making beds."

In light of these economic issues and other problems Turcios mentioned — including a health care system that lacks capacity to meet people's needs; schools with poorly trained teachers that have become recruiting grounds for gangs; and polluted, scarce and unevenly distributed water — migration has become people's only hope.

Especially for the youth, "their future is in the U.S.," Turcios said. "They all fight to come here. It's a dream. The phrase they use is 'el pais de los sueños' (the land of dreams)."

Fr. Estefan Turcios Carpaño is pictured March 21 at St. Sabina Parish in Belton, Missouri, where he was visiting for the annual Romero celebration. (NCR/Maria Benevento)

Along with the low cost of living, remittances that Salvadorans living in the U.S. send back home are one of the few things helping people get by, Turcios said. When migrants start their own families and have less extra cash to send, that often impels yet another family member to migrate and start sending remittances.

Those who can't go to the U.S., especially young people, are often pulled into gang life out of desperation and because they are threatened if they don't join. Extortion and theft from gangs make it even more difficult for people to survive on their earnings from informal work or low income jobs, while the sheer prevalence of gangs makes it difficult to ever feel safe.

Police are often threatened into permitting or even supporting gang activities. A threatened police officer "has to acquiesce, and becomes, little by little, a collaborator, bringing resources, bringing weapons," even sharing information about which person reported a gang member to the police, Turcios said.

When he hears confessions every week, "How many people come to me and tell me they know who killed the neighbor? They saw. But they can't say it."

"Go to the police!" Turcios urges. He even offers to go with them.

As he imitates the typical response, Turcios screws up his face and clenches his fists, speaking in a strained, strangled voice, conveying the impression of someone about to burst from the tension between the desire to denounce, and the overwhelming fear of what will happen if they do.

"No," he whispers. "No, they're going to kill me."

His impression of priests searching for a response to gang violence is similar, portraying a sense of extreme frustration at inadequate options.

"Do you think we're prophets?" he asks. "It's not so easy."

The hands of Fr. Estefan Turcios Carpaño, national director of the Pontifical Mission Societies in El Salvador and director for the human rights office for the Archdiocese of San Salvador are seen during an interview Dec. 27, 2018, in Washington. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

While Turcios hasn't found cases of gang members extorting the church, he said priests know that people connected with gangs hear whatever they say. If collaborators report that a priest said something the gang doesn't like, a member might stop by to warn the priest to be quiet.

But threats aren't the only thing preventing priests from scolding gang members. They also know it's not particularly fair or helpful, Turcios said. "The youth are victims of a national structure. … They're the fruit of this society. They know that we're not in agreement with what they're doing. … But it's because the young people haven't had, nor have, nor will have, a society that thinks about them."

Until the societal roots of gang violence are addressed, Turcios thinks, no law enforcement plan will be able to permanently rid the country of gangs.

He worries that since the end of the Salvadoran civil war, working people have become complacent and trusted left-wing politicians with the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, or FMLN, to look out for their interests.

As problems persist, Turcios is concerned people have just shifted their hope to another party. This February, in a surprise victory, former San Salvador mayor Nayib Bukele, candidate of new right-wing party Grand Alliance for National Unity, or GANA, beat out both the FMLN candidate and the candidate from traditional right-wing party Nationalist Republican Alliance, or ARENA.

Although Bukele won a majority of the vote in the first round, making a runoff unnecessary, Turcios doubts he'll have enough cooperation from the legislature to be able to follow through on his promises. He's afraid people will become even more hopeless if Bukele fails.

From the church's perspective, "all of this worries us because something has to be done but which way do we go?" Turcios said, calling Salvadoran society "fragmented."

While the church doesn't have a "blueprint" for resolving all the problems, Turcios says the renewed appreciation for Romero can help guide its response.

Young clergy who love Romero, but were formed in a time when it was prohibited to even wear a Romero T-shirt, haven't had practice with community organizing or struggling for justice, and might romanticize the idea, Turcios said. The first step is to engage in reflection, then to go out and defend the most humiliated.

Church priorities, rather than being specific plans, are more about attitudes that lead to the right kinds of action whenever necessary, Turcios said, such as "coherence between faith and life," "a more incarnated Gospel," or being a church that is involved with the people rather than being all talk and celebrations.

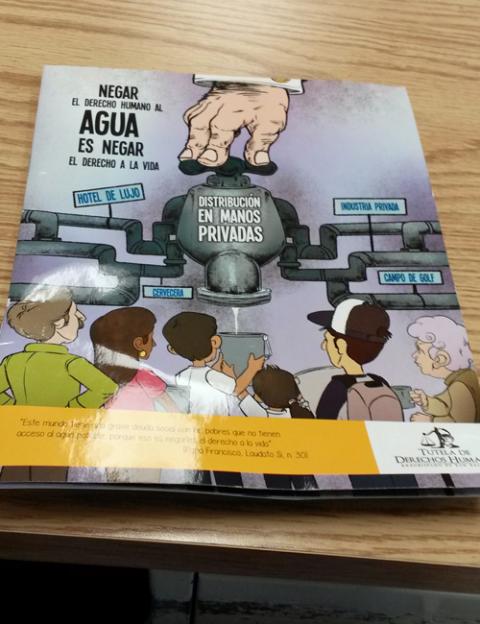

A brochure from the human rights office of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, opposing the privatization of water in El Salvador, is pictured in this March 27 photo. The title reads: "To deny the human right to water is to deny the right to life." (NCR/Maria Benevento)

The concrete results of those attitudes can be as simple as a diocesan soccer league, which helps build community and faith among the young men who participate. Another example is a brochure from the human rights department of the Archdiocese of San Salvador opposing the privatization of water.

Titled "To deny the human right to water is to deny the right to life," the front shows a giant faucet labeled "distribution in private hands" with pipes labeled "luxury hotel," "brewery," "private industry" and "golf course" diverting most of the water. Only a trickle is left for a crowd of people with buckets and mugs.

In a Romero-style synthesis of faith and practical issues, the brochure combines statements from church leaders — such as an excerpt from "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" and a letter from the bishops' conference — with an analysis of the reality in El Salvador including data, timelines and comparisons of government plans for addressing the water situation.

"This is one of the most beautiful things, which we need to take up today: [Romero] took the life of the people seriously," Turcios said. "That's why Monseñor Romero is so valuable. If we take the problems seriously — hunger, human dignity — that can change us."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]

Advertisement