People look at a painting of slain Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero at the cathedral in San Salvador in 2015. (CNS/Reuters/Jose Cabezas)

The conventional wisdom about Óscar Romero goes like this: When a right-wing death squad killed a priest friend of his soon after he became archbishop, Romero — until then a staunch conservative — experienced a dramatic, indeed life-changing, conversion.

The conventional wisdom is gravely mistaken.

Romero himself rejected it, as did those who knew him best. Abundant evidence exists, but for me the clincher is a story told by Paul Schindler, a Cleveland priest who worked in El Salvador before and during Romero's years as archbishop of San Salvador. Schindler was pastor of the parish where Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel and Jean Donovan — two of the four U.S. churchwomen raped and murdered in 1980 by government troops — lived and worked. I told his story in ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America (Spring 2016):

Fr. Paul Schindler remembers the day when Óscar Romero sat beside him, trembling. Romero knew he wasn't among friends. The scene was a clergy meeting in early 1977, and many of the priests were furious: a man they'd clashed with — Romero — had just been named as the new archbishop.

As the meeting was ending, Romero — who hadn't yet been installed — was asked if he'd like to say a few words. For all Schindler knew, they would be the last words he'd ever hear from him. Discouraged at the prospect of working under [Romero] ... Schindler had told his bishop back in Cleveland that he'd decided to return home after eight years of parish work in El Salvador.

"He walked to the front of the room and began to speak," said Schindler, "and after a half hour, I said to myself, 'I'm not going anywhere.' "

Having packed his bags, Schindler decided to unpack them and continue working in El Salvador after hearing Romero. This was before Romero took office as archbishop, and before the slaying of Romero's priest friend, Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande.

What had happened? Unbeknownst to Schindler — and to many others — Romero had changed during an extended stay, in the mid-'70s, far from the capital city. In the early '70s, as an auxiliary bishop in San Salvador, he was seen as highly conservative; that was the period when he drew the ire of the priests who were so upset by the news of his appointment as archbishop. But in 1974, he was named bishop of the rural diocese of Santiago de María. There, he drew close to farmworkers and catechists who were targeted by the military. What he saw led him to a major shift in outlook.

" 'Monseñor, they say you've been converted. Is it true?' I remember his answer well: 'I wouldn't say it's been a conversion, but an evolution.' "

—Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chávez

During Romero's first year in Santiago de María, the National Guard massacred farmworkers in the village of Tres Calles. After visiting the scene, Romero wrote a letter to the then-president, Col. Arturo Molina, expressing his "firm protest" for

… the way in which a "security force" had wrongfully acted, as if it had the right to mistreat and kill. … [I went there] to console the families that had been attacked … by a squad of National Guardsmen. On the way to their homes, I stopped to pray by the body of a still-unburied victim who had been shot in the head. His wife and mother were beside him, weeping. When I arrived at the houses that had been invaded by the armed forces, it broke my heart to hear the bitter laments of the widows and orphans who, sobbing inconsolably, told me about the attack.

As Kevin Clarke recounted in Oscar Romero: Love Must Win Out: "Romero later visited the local [National Guard] commander to protest the massacre. The officer shrugged the killings off as a trivial accounting with local malefactors, and [said], pointing a finger at Romero, 'Cassocks are not bulletproof.' "

Romero was beginning to get the picture.

When he arrived in the diocese, landowners insisted he shut down a local pastoral center that offered training aligned with the church's post-Vatican II thinking. The landowners were especially upset by a priest who taught there. They claimed he was a communist.

One night, Romero went to the center and, without the priest knowing it, stood outside his classroom, listening to his presentation. Romero found nothing unorthodox in it and, when asked later about the priest, commented, "If he's a communist, I'm a Martian."

Still, he did close the center — temporarily. When his decision was challenged, he agreed to reconsider it, and eventually, to the consternation of the landowners, he reopened the center.

Romero was appalled by the suffering of itinerant farmworkers — often entire families, including spouses and children — who came to the area to work in the coffee harvest. Obliged to spend the chilly nights sleeping outdoors on the ground, they often ended up sick. Earlier, Romero had quoted approvingly the passage in Pope Leo XIII's encyclical on labor and capital (Rerum Novarum, 1891) that condemned the practice of workers being "handed over, alone and defenseless, to the inhumanity of owners." Now, he opened church buildings at night to offer them food and shelter, and often spent his evenings with them, hearing about their travails.

It was clear that for them to have a decent life, the country would have to undertake a major agrarian reform, returning the lands that had been taken from them earlier. That prospect was unthinkable to the landowners, so much so that when the country's military dictator announced a small land reform as a tactic to weaken the surging farmworker protest movement, the landowners forced him to scuttle it.

Undaunted by the owners' hostility, Romero regarded the land reform issue as so important that he scheduled a three-day conference on the subject for the priests and laity of the diocese, inviting experts from San Salvador to come and give the talks. Years later, one of the experts, Rubén Zamora, said, "I still have this image of him at those talks: sitting at a schoolchild's desk in the front row, taking notes, listening very attentively. You could see he really wanted to learn. His concern was, how could the church help?"

These experiences and others are detailed in a book whose title is a quote from Romero: In Santiago de María, I Came Face to Face With Misery (edited by Zacarías Díez and Juan Macho Merino, 1995). He was so affected by what he saw there that when he returned to San Salvador in 1977 and gave the talk that turned Paul Schindler around, it was clear that he himself had been turned around.

I asked María López Vigil, a journalist, editor and author of Monseñor Romero: Memories in Mosaic, how she saw Romero's evolution:

People have almost mechanically related Romero's conversion to the killing of Rutilio and the surrounding events. I think that's excessive. … It wasn't ideas that changed [Romero]. It was reality. That's basic. When he was an auxiliary bishop in San Salvador, his contact with reality was limited by his job [secretary of the bishops' conference] and by the office he worked in. When he was in Santiago de María, at a time of repression, he drew near to the farmworkers in their suffering, their work, and their commitments as catechists, and all of that changed him. I think it's important to highlight that so as not to oversimplify his process of conversion. What happened to Rutilio was the culmination of a journey he had been on.

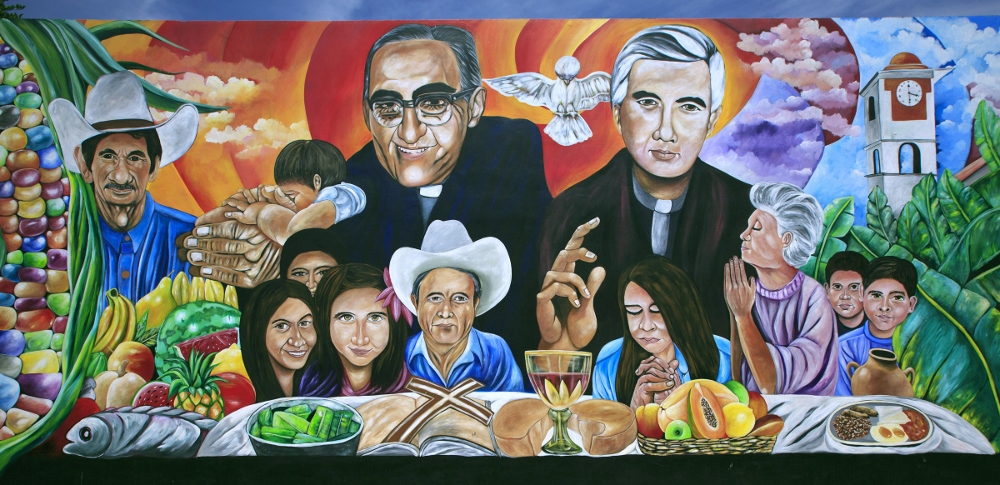

A mural of Archbishop Óscar Romero and Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande is seen in El Paisnal, El Salvador, in 2016. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

Disputing the 'Rutilio miracle'

In a recent tribute to Romero, the eminent moral theologian Fr. Charles Curran wrote, "What many called the 'Rutilio miracle' was the reality that brought about [Romero's] commitment."

Surely the killing of Grande was painful for Romero, given how close they were, but it was not the "miracle" that some — peace activist John Dear, for example — insist it was. "Suddenly," wrote Dear in NCR, "the nation had a towering figure in its midst. … Standing over Grande's dead body that night, Romero was transformed into one of the world's great champions for the poor and oppressed."

But Romero wasn't "suddenly … transformed" or "converted"; his change was a process that had been going on for several years before Grande's murder.

It's also important to rebut Dear's claim about who Romero had been earlier: "He sided with the greedy landlords, important power brokers, and violent death squads." That egregious falsehood has absolutely no basis in fact. On the contrary: Even before his time in Santiago de María, Romero had denounced as "unjust" those laws that favored "the interests of legislators and the ruling minority."

The feature film "Romero" is another of the culprits fostering the belief that Romero's change was all about the killing of Grande. In addition to its other falsehoods (e.g., the film has Romero being arrested and jailed and, on another occasion, detained and stripped, and it has one of the Jesuit priests who worked with Grande taking up arms — none of which happened), "Romero" invents a rupture between Grande and Romero just before Grande was killed, with Grande angrily saying to Romero:

Don't you see what's going on around here? Anyone who says what he thinks about land reform or wages or God or human rights … automatically he's labeled a communist … He lives in fear … They take him away … They torture him, they kill him … You don't believe me, do you?

Goodbye, Óscar.

This is a total fabrication. Romero did know what was going on, and Grande, far from breaking with him, was constantly standing up for him, trying to convince reluctant priests to give him a chance. A rupture between the two? No way. Of course, if you've decided that your film will present Grande's murder as a "road to Damascus" moment in which Romero, like Paul, was suddenly "converted," the rupture narrative sets things up nicely. There's only one problem: It's not true.

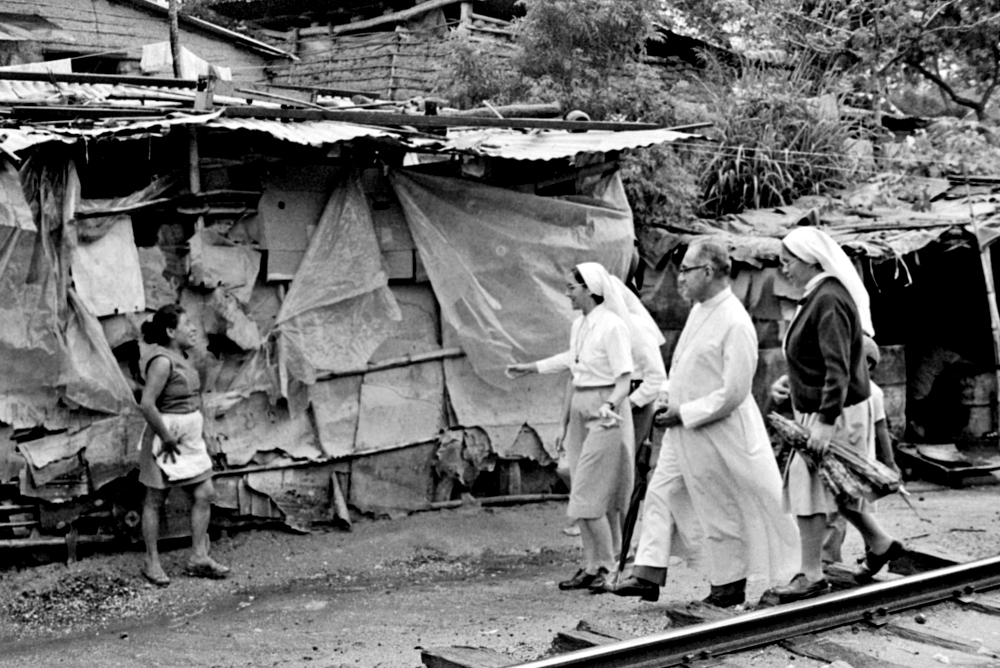

Archbishop Óscar Romero visits La Chacra in San Salvador, El Salvador, in 1979. (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick) *

In fact, Romero objected to people speaking of his "conversion." Salvadoran Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chávez says, "I once asked him the following question: 'Monseñor, they say you've been converted. Is it true?' I remember his answer well: 'I wouldn't say it's been a conversion, but an evolution.' "

It was, as Romero wrote on another occasion, "an evolution of the same desire that I have always had to be faithful to what God asks of me; and if earlier I gave the impression of being more 'prudent' and more 'spiritual,' it was because I sincerely believed that in that way I responded to the Gospel, because the circumstances of my ministry were not as demanding as those when I became archbishop."

Msgr. Ricardo Urioste was Romero's vicar general and perhaps the person closest to him. He, too, disputes the claim that there was a "Rutilio miracle":

It is said of Archbishop Romero that he changed drastically with the murder of Fr. Rutilio Grande, and that his conversion happened less than a month after he became archbishop. I don't believe this is so. … [He] began to see gradually, as he discovered more about the Gospel, the church's magisterium, and the painful situation of the people. All of these changed him. He never spoke of himself in terms of conversion; he spoke of evolution. For this reason, he wrote about "readiness to change. He who fails to change will not gain the kingdom."

The fullness of church teaching

Another common misconception about Romero is that he was an ecclesiastical rebel who acted with little regard for the institutional church. Not true, says López Vigil:

I found that he was tremendously faithful to the institutional church and the grassroots church — to both. … He was born, grew up, matured and died with an immense fidelity to the institutional church, so I would see him as "within it" and not "in spite of it."

Thus, the stands Romero took — stands that got him into trouble and eventually got him killed — were not instances of him ignoring church doctrine or rebelling against it, but rather of him faithfully taking it to its fullest consequences — as he did, for example, with Catholic social teaching.

Advertisement

The most famous example came in the closing words of his homily on the eve of his murder. On that occasion, as Julian Filochowski, chair of the Romero Trust, writes, "[Romero] tackled the thorny question of what ordinary soldiers should do when ordered to kill and massacre." Said Romero:

Before an order to kill that a man may give, God's law must prevail: Thou shalt not kill! No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God. … It is time to obey your consciences rather than the orders of sin. In the name of God, therefore, and in the name of this suffering people whose cries rise to heaven more loudly each day, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression!

When Romero made that plea, Thomas Quigley, an adviser to the U.S. bishops' justice and peace office, was sitting in the sanctuary a few feet away. Quigley later wrote, "He told soldiers, simple peasants themselves for the most part, that they are not bound by unjust orders to kill; standard textbook theology, but if applied in the concrete, usually considered treasonous. It was so described in the Monday morning paper by an Army spokesman."

Romero was murdered Monday evening while celebrating Mass. "Standard textbook theology" had been deemed punishable by death.

A woman prays in the chapel of Divine Providence Hospital in San Salvador May 21, 2015, two days before the beatification of Archbishop Óscar Romero, who was shot as he celebrated Mass in the hospital chapel March 24, 1980. (CNS/Lissette Lemus)

Urioste recalled another occasion when Romero gave a particularly forceful homily. Afterward, Urioste told him he feared it would provoke a violent response. Romero replied, "I had to say it. If I'd said anything less, I would have fallen short; I wouldn't have been expressing the fullness of church teaching." For that reason Urioste, when asked what kind of martyr Romero was, replied, "He was a martyr for the magisterium." It is fitting, then, that Curran includes in his tribute to Romero a famous example of magisterial teaching taken from "Justice in the World," the declaration of the 1971 international synod of Catholic bishops:

Action on behalf of justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel, or, in other words, of the Church's mission for the redemption of the human race and its liberation from every oppressive situation.

All too often those words have been ignored, but not by Romero. He lived them out in his ministry. For doing so, he was accused of being anti-government. No, he said, "the conflict here isn't between the church and the government; it's between the government and the people, and the church is with the people." This ended up leading to clashes with the authorities, but as Curran noted:

Romero's struggle against the government and its injustices did not [amount to] unacceptable involvement of the church or church leaders in the world of politics. Whatever affects human persons, human communities, and the environment is by that very nature not just a political or a legal issue. It is a human, moral and, for the believer, Christian issue. The Christian tradition has consistently recognized that the political order is subject to the moral order.

That vision of the church's role — shared by Romero but rejected by those who blocked his canonization process for years — was ratified by Pope Francis when he unblocked the process and moved it forward.

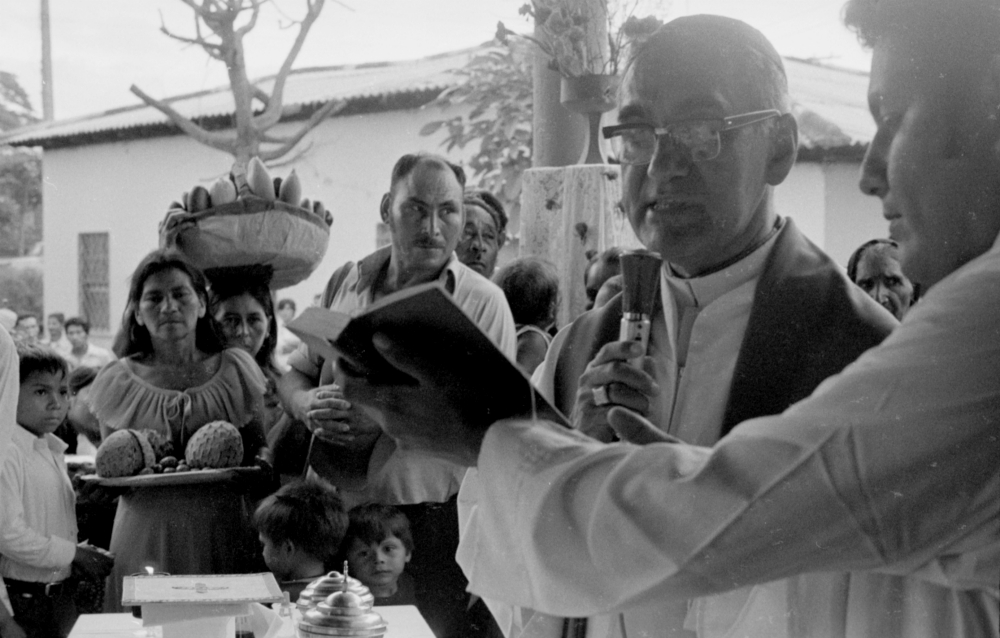

Archbishop Óscar Romero presides at a confirmation Mass in Ateos in San Salvador, El Salvador, September 1979. (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

Nor did Francis stop there; he did something else that had long cried out to be done. Many people aren't aware — but Francis was − of how shabbily Romero was treated by all but one of his brother bishops. Seldom has there been a condemnation of bishops as strong as the one Francis expressed to a group of Salvadoran pilgrims who were visiting the Vatican in 2015:

I would … like to add something that perhaps has escaped us. Archbishop Romero's martyrdom did not occur precisely at the moment of his death; it was a martyrdom of witness, of previous suffering, of previous persecution, until his death. But also afterwards because, after he died — I was a young priest and I witnessed this — he was defamed, slandered, soiled — that is, his martyrdom continued even by his brothers in the priesthood and in the episcopate. I am not speaking from hearsay; I heard those things.

It was good to see — at long last — Romero vindicated in that way.

'We all have our roots, you know'

On a visit to the Vatican in the late 1970s, Romero was accompanied by Fr. César Jerez¸ then the Jesuit provincial for Central America. Earlier in the '70s, Romero had attacked the Jesuits for the consciousness-raising work they were doing in their elite San Salvador high school. He was also a leader of the effort that got the Jesuits expelled from the interdiocesan seminary, where they had served as faculty for decades; and he alluded unfavorably to the writings of Jesuit Fr. Jon Sobrino, a prominent liberation theologian who was teaching at the Jesuit university in San Salvador.

'Yes, I changed. But I also came back home again.'

—Archbishop Óscar Romero

But when Romero returned to the capital as archbishop in 1977, he invited the Jesuits to produce a daily hourlong news and commentary program for the archdiocesan radio station, and he consulted Sobrino, among others, when he was preparing his pastoral letters.

Jerez tells of a night when they took a walk along the Via della Conciliazione:

I got up my courage and tried to get him to speak. "Monseñor, you've changed … What's happened?"

"You know, Father Jerez, I ask myself that same question when I'm in prayer …"

"And do you find an answer, Monseñor?"

"Some answers, yes … It's just that we all have our roots, you know … I was born into a poor family. I've suffered hunger. I know what it's like to work from the time you're a little kid … When I went to seminary and started my studies, and they sent me to finish studying here in Rome, I spent years and years absorbed in my books, and I started to forget where I came from. I started creating another world. When I went back to El Salvador, they made me the bishop's secretary in San Miguel. I was a parish priest there for 23 years, but I was still buried in paperwork … Then they sent me to Santiago de María, and I ran into extreme poverty again. Those children that were dying just because of the water they were drinking, those campesinos killing themselves in the harvests … You know, Father, when a piece of charcoal has already been lit once, you don't have to blow on it much to get it to flame up again … So yes, I changed. But I also came back home again."

A crowd of people from San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, walk with Archbishop Óscar Romero as he arrives to celebrate Mass in 1979. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

These words underscore that it was his experience in Santiago de María, and not a "Rutilio miracle," that brought about Romero's commitment. Nevertheless, the killing of Grande did help to crystallize that commitment, leading Romero to take drastic measures. When he'd written to the president two years earlier about the Tres Calles massacre, he kept the letter private, but after Grande's murder he went public, denouncing the crime and declaring that if the government failed to do a serious investigation, he would boycott — as, in fact, he later did — all government events, including the upcoming inauguration of the country's new president.

In addition, feeling that a sign of church unity was needed after the attacks on Grande and other pastoral workers, Romero decreed that on the Sunday following Grande's death, all Masses in the archdiocese would be suspended, and a single Mass would be celebrated at the cathedral, with the entire archdiocese invited to attend. He also canceled classes in the Catholic schools for three days, ordering the schools to devote those days to a study of the country's problems.

These gestures upset the army and the government, and enraged both the papal nuncio and the group of Salvadoran bishops whom Pope Francis would later denounce. The nuncio had recommended Romero's appointment as archbishop, thinking he would be a docile, manageable figure. Now it was the nuncio's turn to be surprised, just as Paul Schindler had been.

How to explain Romero's actions? He put it this way: "When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead, I thought, 'If they killed him for doing what he did, then I have to walk that same path.' " And he did walk it, knowing full well what the consequences of that commitment could be. In a homily on Nov. 11, 1979, he made it clear that there would be no turning back: "I ask for your prayers to help me be faithful to this promise: that I will not abandon my people, but will, with them, run all the risks that my ministry requires of me."

A man prays at the grave of Blessed Oscar Romero in 2017 at the Metropolitan Cathedral in San Salvador, El Salvador. (CNS/Reuters/Jose Cabezas)

'The pastor is supposed to be there for the flock'

I once had the chance — it was a gift, really — to hear him express that commitment in person. It was at the meeting of Latin American bishops in Puebla, Mexico, in 1979. Just before Romero left El Salvador for Puebla, the National Guard had murdered Octavio Ortiz, a priest to whom Romero had been like a second father. Both grew up in poor families in rural areas of eastern El Salvador; both entered the seminary at a very young age. Ortiz was the first priest Romero ordained after being consecrated a bishop.

The Guardsmen shot Ortiz — along with four others at the weekend youth retreat he was giving — and then rolled a tank over his head. Romero denounced the government's version of the incident as "a lie from beginning to end." In those days, with a military dictatorship ruling El Salvador, statements like that could easily become a person's last words; even before that, Romero had been getting serious death threats.

One day at Puebla, a few journalists were talking with him. One of us, without mentioning the threats explicitly, asked, "Are you really going back to El Salvador?" — as in (but not actually saying), "If you do, they're going to kill you."

"I know what you're getting at," said Romero, "but, you know, they say I'm the pastor, and the pastor is supposed to be there for the flock. And the flock is back in El Salvador. So, yes, I'm going to return."

One doesn't forget remarks like that. I went home to New York after Puebla and began saving money for a plane ticket to El Salvador. I was preparing to depart when, on a Monday night, I went to a parish to hear a talk on liberation theology. At the end of the evening, as we emerged from the meeting room, the sacristan was there, waiting to lock up the church. Transistor radio in hand, he asked, "Weren't you people talking about Latin America?"

"Yes."

"Well, they just said on the radio that somewhere down there tonight, a bishop was shot and killed."

I would go to El Salvador, but I would never see him again.

[Gene Palumbo is a freelance journalist based in El Salvador. He went there in 1980 immediately after Romero was murdered and ended up staying on, covering the country's civil war (1980-92) and its aftermath. He is The New York Times' local correspondent in El Salvador, and has also reported for National Public Radio, the BBC, the Canadian Broadcasting Company, Commonweal Magazine and Time Magazine.]

*The original verison of this story had an incorrect caption on a photo.