President Joe Biden departs St. Joseph on the Brandywine Catholic Church after attending Mass in Wilmington, Del., April 23, 2022. He carries a rosary in his pocket and plans his public schedule to allow him to attend Mass on Sundays and holy days. (CNS photo/Tasos Katopodis, Reuters)

One bishop called him an "evil" president. Another bishop said he was "stupid." The archbishop of Washington D.C., once described him as "a cafeteria Catholic" on national television. Some prelates wanted to deny him Communion altogether.

President Joe Biden, only the second Catholic president in the United States' nearly 250-year history, has had a strained relationship, at best, with the U.S. Catholic hierarchy. Even before he took the presidential oath of office in January 2021, at least one bishop years earlier had used the term "Joe Biden Catholic"as a pejorative.

But when Biden leaves the Oval Office in January, it will mark not only the eclipse of a 50-year political career but also the departure of a Catholic commander-in- chief who always carried a rosary in his pocket, peppered his speeches with religious references and arranged his public schedule to attend Mass on Sundays and on holy days of obligation.

'Biden has lived his life wanting to live the council's vision of the church getting closer to and embracing the world. The ending of his presidency, I think, reflects the ending of that era in the United States in the Catholic Church.'

—Steven Millies

"If you talk to his staff, they will tell you, Mass is very important to him," said Sr. Carol Keehan, a Daughter of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul and the former president and CEO of the Catholic Health Association of the United States.

The only Catholic to be elected president since John F. Kennedy in 1960, Biden's legacy as a Catholic president is one shaped by historical and cultural forces in the church and the wider culture.

A public servant whose political consciousness was formed in the early days of the Second Vatican Council and its call for Catholics to engage the world in a spirit of openness, Biden's ascent in Washington's power circles coincided with the Catholic Church in the United States increasingly taking a confrontational posture toward secular modernity.

"Biden is a person who has lived his life wanting to live the council's vision of the church getting closer to and embracing the world. The ending of the Biden presidency, for all intents and purposes, I think, reflects the ending of that era in the United States in the Catholic Church," said Steven Millies, director of the Bernardin Center at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

Pope Francis speaks briefly with U.S. President Joe Biden during the Group of Seven summit in Borgo Egnazia in Italy's southern Puglia region, June 14. An October 2021 meeting with Francis at the Vatican had rankled some U.S. churchmen. (OSV News/Reuters/Louisa Gouliamaki)

Elected a U.S. senator from Delaware in 1972, Biden’s political career also overlapped with significant social changes in the United States, including the rise of abortion politics and the successes of the LGBTQ rights movement. Biden's accommodations to those movements may have helped him in Democratic party circles, but against a backdrop of growing polarization they also alienated him from a U.S. Catholic hierarchy less willing than it had been with Kennedy in the 1960s to tolerate a president who in some instances separated his faith from governing.

"The bishops who did not like the idea of a Catholic like John F. Kennedy in the White House kept quiet about their concerns," said Massimo Faggioli, a theologian and church historian at Villanova University.

In the 1960s, American Catholicism was not as polarized around hot-button issues as it is today, Faggioli told the National Catholic Reporter. In Biden's case, Faggioli said, abortion and gender have "been used to build a wall of separation" between the president and the bishops in a manner that is hard to find in other countries, even when the heads of state and episcopates in those nations disagree on important issues.

"One important factor is the American two-party system which has created two different and opposite worldviews," Faggioli said. "This bipartition happened also in the church, where political identities, affirmed defiantly, have replaced the coexistence of different but compatible theological and religious ways of being Catholic."

A 2020 campaign video shows a photo of Joe Biden holding hands with others in prayer, while Biden reflects in a voiceover on how faith would get America through the coronavirus pandemic.* (NCR screenshot/Joe Biden for President)

As a politician, Biden's "way of being Catholic" was a complex mixture of symbols, phrases and policy priorities inspired by his working class Catholic upbringing in Pennsylvania and Delaware, where he attended parochial schools. He often made the sign of the cross at public events. He accentuated his electoral victory speech in 2020 by quoting the Catholic hymn, "On Eagle's Wings." In his Jan. 20, 2021, inaugural address, Biden referenced St. Augustine.

When he launched his 2020 campaign for the White House, Biden spoke of battling "for the soul of the nation." A campaign video from that year shows a photo of Biden holding hands with others in prayer, while Biden reflects in a voiceover about how faith would get America through the coronavirus pandemic.* That same year he delivered a eulogy for George Floyd and cited Catholic social doctrine that he said had taught him that "faith without works is dead."

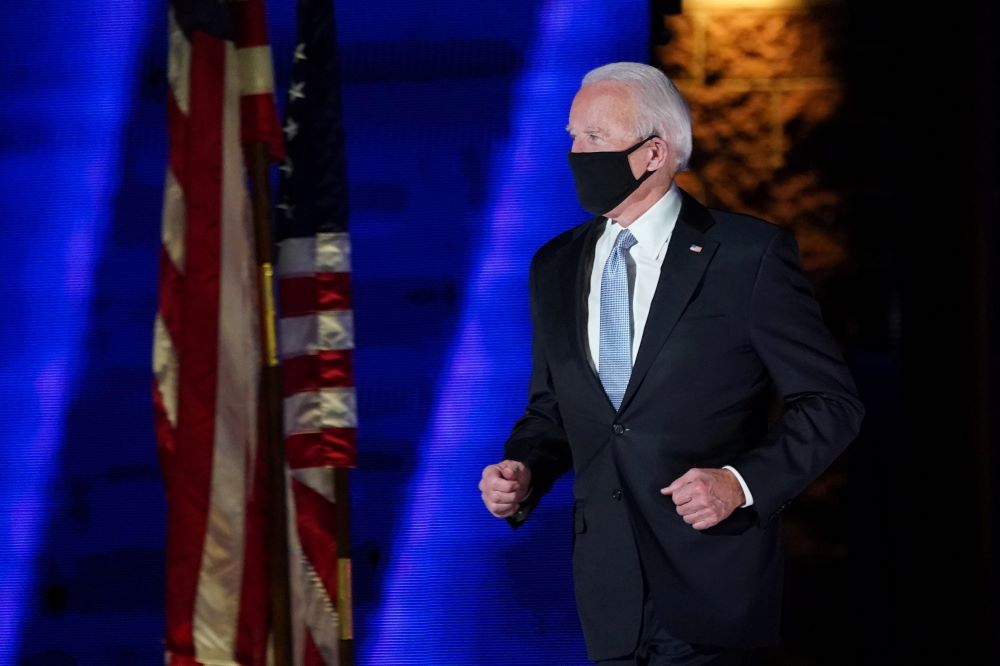

Joe Biden accentuated his electoral victory speech Nov. 7, 2020 by quoting the Catholic hymn, "On Eagle's Wings." Here he runs onto the stage at a rally in Wilmington, Del., after news media declared he had won the presidential election. (CNS/Reuters/Kevin Lamarque)

"He has a very very strong devotion to Catholic social justice," Keehan said. “He understands that you just don't go to church and say prayers. Your life has to be a life of faith. It has to be an effort for justice and for fairness, and for helping people who don't have the same opportunities that you have."

Keehan, whose advocacy for the Affordable Care Act was crucial in getting that landmark health care law passed in 2010, told NCR that Biden, who was then the vice president in President Barack Obama's administration, always made himself available to her when needed.

Then-Vice President Joe Biden watches as U.S. President Barack Obama signs the health care legislation during a ceremony in the East Room of the White House March 23, 2010. (CNS/Reuters/Jim Youngs)

"I always knew if I needed to talk to him personally on some issue, that I could get to him," Keehan said.

On matters of economic and social justice, Biden’s political positions align with and appear to be influenced by Catholic social teaching principles.

In addition to supporting health care reform, Biden has championed labor unions, racial justice efforts, programs to help the poor and middle class, clean energy initiatives and U.S. leadership on mitigating climate change. He has spoken of securing the border while also welcoming migrants and reforming the nation's immigration system.

In October 2021, Biden met with Pope Francis at the Vatican, a meeting that rankled some U.S. churchmen. In that meeting, Biden later told reporters that the pope called him a good Catholic and encouraged him to keep receiving communion.

"To say that he doesn't have any Catholic legacy as vice president would certainly not be true," said Charles Camosy, a medical humanities professor at Creighton University. Camosy told NCR that Biden in many aspects has been "unafraid" to invoke his Catholic faith in public life.

"But at least as how it sort of played out in his time as president, when we're talking about his Catholicism, he only really focused on aspects of his faith that were already sort of along the lines of the secular commitments of his party," Camosy said.

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks next to Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers, as he joins striking UAW members on the picket line outside the GM's Willow Run Distribution Center in Belleville, Mich., Sept. 26, 2023. (OSV News/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

In addition to Biden's decision to align with his party's position on abortion, Camosy suggested that Biden could have better reflected a "Pope Francis vision" by being more skeptical of war and armed conflict, rather than supplying arms and military aid to combat theaters in Ukraine and the Middle East.

"As president, his is a much less complicated and interesting legacy than he had before he became president," said Camosy, who noted Biden's earlier positions on abortion rights.

As a young senator in 1974, Biden opined that the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade had gone "too far." Commenting on the high court's ruling that had declared abortion to be a constitutional right, Biden told The Washingtonian, "I don't think that a woman has the sole right to say what should happen to her body."

Later in his career, Biden endorsed Roe v. Wade, but supported compromises with antiabortion colleagues such as the Hyde Amendment, a legislative provision that prohibits the use of federal funds to pay for abortions. But when he ran for president in 2020, Biden reversed his support for the Hyde Amendment and has since said he supports making Roe v. Wade — overturned by the high court's 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Women's Jackson Health Organization — the law of the land.

A woman protests abortion as Joe Biden, then U.S. Democratic presidential nominee, attends church in Wilmington, Del., in this Nov. 1, 2020, file photo. (CNS photo/Reuters/Kevin Lamarque)

Kristen Day, executive director of Democrats for Life, said that under Biden's leadership, the Democratic Party became even more "inhospitable" for pro-life Democrats. She told NCR that her group has not gotten an audience with the leadership of the Democratic National Committee during the Biden administration.

"This is Joe Biden's legacy, putting the final nail in the coffin for pro-life people in the party," Day said.

Referring to abortion as "the elephant in the room," Keehan took issue with characterizations of Biden as a "pro-abortion" politician.

"I don't think anybody who knows or who has watched Joe Biden would ever say he is a proponent of abortion," she said. "He's a proponent of choice. That is a different thing."

Biden's increasingly liberal stances on abortion prompted the U.S. bishops' conference in 2020 to form a working group to examine the purported "difficulties" of Catholic politicians who supported abortion rights. Several outspoken prelates wanted the group to draft a statement that would have made it easier for bishops to deny Communion to Catholic politicians like Biden. In the end, the bishops approved a compromise document that reiterated church teachings on the Eucharist.

Then-U.S. Vice President Joe Biden makes the sign of the cross after receiving Communion during a memorial Mass for Vatican diplomat Archbishop Pietro Sambi Sept. 14, 2011, at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington. (CNS/Leslie Kossoff)

Camosy said he thought it was a good idea in principle for the bishops to engage a difficult topic like Catholic politicians who support abortion rights, though he added that the way the prelates pursued that matter made it seem like they were engaged in a partisan undertaking.

“I would have loved, for instance, for some of that fire to be trained on Catholics who are Republicans who don't always line up with very serious teachings of the church, say on welcoming the stranger, on economic justice, on the death penalty, things like that," Camosy said.

On controversial, divisive issues like abortion, Faggioli suggested that no one except an "integralist Catholic" would expect the president of the United States to champion his church's teachings in a multi-religious and multicultural country. In some sense, Faggioli said, Biden's Catholicism became "more private once he took office."

"But he also did not articulate the distinction, if there is one, between his personal positions on abortion and gender from the positions of the Democratic Party. And he did not articulate how they were influenced by his Catholic faith.

"This is a particular problem that only a Catholic president has, given how Catholicism works, its hierarchical structure and magisterial texts," Faggioli added. "It's a problem that a Protestant or Jewish or Muslim president would not have, or that they would have in a very different way. But it's also because the platform of the political party on some social issues has become almost dogmatic. And thanks to social media, a discussion on some issues within one party has become even more difficult than in the Catholic Church."

Further complicating the story of Biden's Catholic political legacy, said Millies of Catholic Theological Union, has been the unfolding reception of the Second Vatican Council in the United States that took a more confrontational approach to the modern world during the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict XVI. That, along with abortion politics, changed the U.S. Catholic hierarchy's relationship to political life.

"Or maybe it's better to say, that those things together began to restore the church's relationship [to political life] prior to what it was before 1960, when there was a greater sense of Catholics being on the outside," Millies said.

Advertisement

So for Biden, his political legacy would appear to be intertwined with that of a certain type of "Vatican II Catholic" who came of age politically in a time, now all but passed, when the U.S. church and Catholics consciously tried to engage and accompany the outside world.

"When Joe Biden leaves the Oval Office in 2025, 60 years after the ending of the Second Vatican council, it's going to mark the definitive closing of that era," Millies said. "And we'll be then waiting for a new one to open."

*This story has been updated to correct details about Biden's 2020 campaign video.