Stained glass window of Clare of Assisi in St. Servatius in Landkern, Germany (Wikimedia Commons/Reinhardhauke)

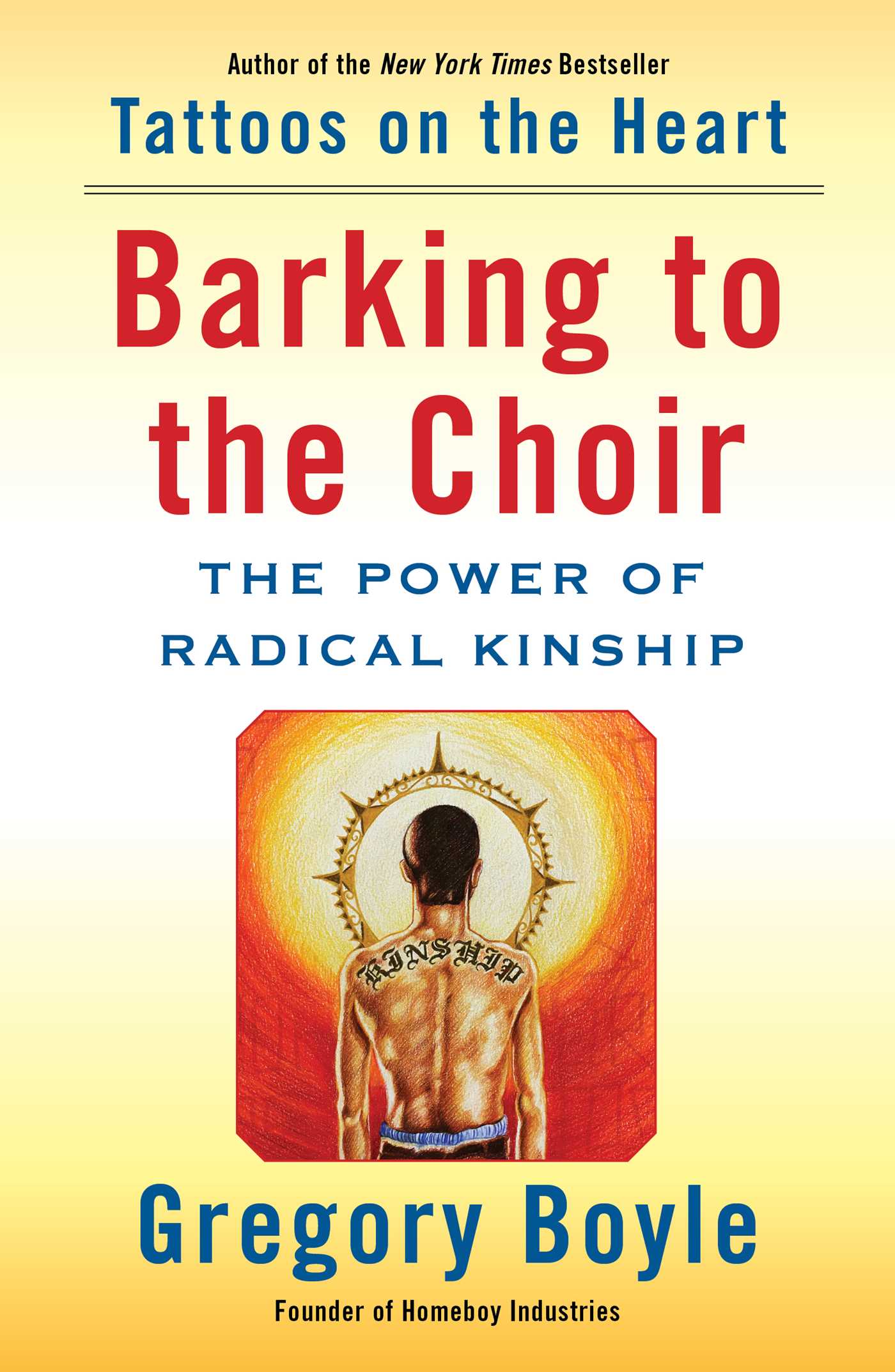

Jesuit Fr. Gregory Boyle spreads the Gospel notion of Jesus Christ's radical kinship with humanity and says we should do likewise. That's the message of his eye-opening new book, Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship.

A Los Angeles native, Boyle works in a high-poverty community in Los Angeles where one in three youths suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. That, he says, is twice the rate of soldiers returning from war. An expert on working with ex-gang members, Boyle has received numerous awards, including the James Beard Foundation Humanitarian of the Year Award and the California Peace Prize.

As he explains it, the "homies" (his term for the men and women who walk into his "Homeboy Industries") bring along "unspeakable acts perpetrated against them, from torture … to abandonment … to terror." His nonprofit provides education and job opportunities for ex-gang members.

After his 1984 ordination, Boyle spent a year working in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with Christian base communities. When he returned to the U.S. in 1986, he asked to be assigned to the Dolores Mission in East Los Angeles.

The mission was located between two public housing projects with the highest concentration of gang activity in the city. As of the writing of this book, he says, he has buried exactly "220 young human beings from gang violence."

The homies are young people who joined gangs to escape the misery of their lives. But gangs led to drugs and shootings and sometimes death. The lucky ones went to prison. But when they were released, the destructive cycle continued.

Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle, who started Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles to help young people avert a life of gangs, drug abuse and street violence, is pictured in a 2005 photo. (CNS/EPA/Armando Arorizo)

Boyle works to break that cycle by treating gang members as human beings and proclaiming the Christian notion of benevolence as opposed to judgment.

This book's title — taken from a verbal slip by one of the homies — suggests the writing's lightheartedness and casual tone. Boyle adds anecdotes about his encounters with the homies, as well as tidbits from his own life, history, health and experience of illness.

Barking looks at the positive effects of Christian fellowship in dealing with ex-gang members. It includes numerous quotations from poets, philosophers, Zen masters and social activists. There are allusions to the Bible, sermons by Martin Luther King Jr., and excerpts from poets as varied as Galway Kinnell, Mary Oliver and the Persian mystic Hafiz, who enjoyed calling out religious hypocrisy.

The many topics give the book a somewhat disorganized feel. Describing this collection of essays as "elongated homilies," Boyle proclaims the largess of God's love, which is his own way of speaking against hypocrisy — religious or otherwise.

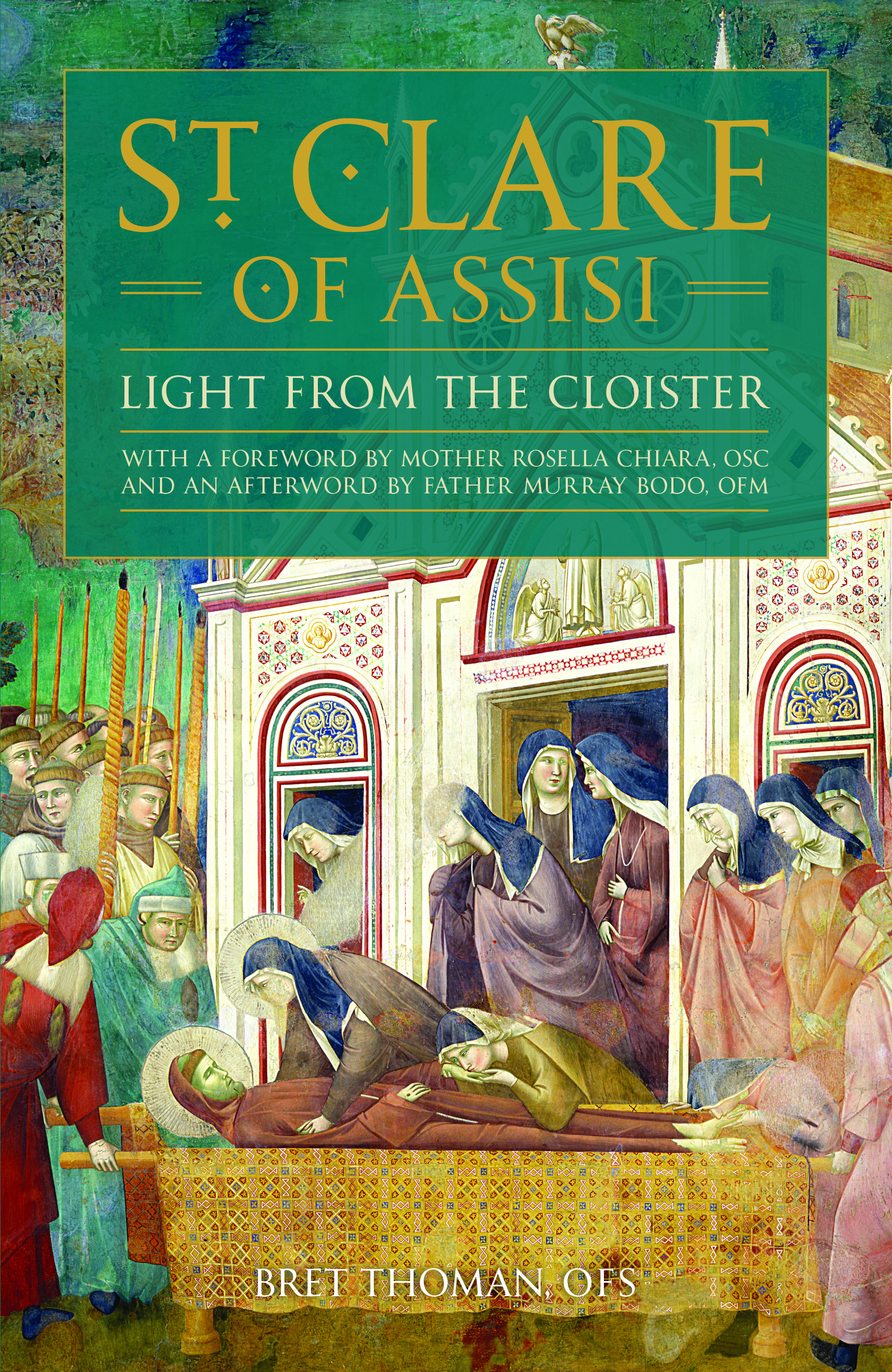

Having heard St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) preach about following the example of Jesus Christ, Chiara Offreduccio (1194-1253) left her family at age 18, declaring that she would wed God. She founded a monastic order for women based on the Franciscan tradition and is believed to be the first woman in the history of the Catholic Church to write the constitution for her order.

Chiara, or Clare, is the subject of Bret Thoman's somewhat disappointing new book. St. Clare of Assisi: Light From the Cloister offers a fictionalized version of the life of a woman who lived in poverty because she believed Christ meant it when he said give away everything you have and follow me.

The daughter of a noble family, she was able to read and write in Italian and Latin in an age when most women were illiterate. She withstood adversity and argued with five popes, refusing the dictates of a patriarchal society. When her father and brothers insisted she marry, she refused. When bishops urged her to allow the ownership of property, she refused.

A mosaic in Assisi, Italy, depicts St. Clare of Assisi. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

Beginning with her mother's pilgrimage to Rome and ending with Clare's canonization, the book includes historical nuggets, like the fact that the Rosary originated as a prayer for illiterate monks and nuns who could not read the Latin Psalter.

It also contains footnotes that serve to, Thoman says, separate fact from fiction. But it's disconcerting when the notes contradict the narrative, as when Thoman invents Francis' sermons, speculates about their effect on Clare, but then in a footnote says that there is no record of any of Francis' sermons.

The records that exist show that Clare lived in Assisi and came from a wealthy family. They also show that her mother inspired her with devotion to the Eucharist. Thoman prefaces each chapter with a quote from the "Song of Solomon" suggesting Clare's almost palpable love of the sacrament.

She and several women, who called themselves the Order of Poor Ladies (Poor Clares), lived in a hut beside the church of San Damiano. They ministered to the poor and spent much time in prayer — wearing rags, owning no shoes and begging for food. According to tradition, Clare miraculously stopped an invasion of Saracen soldiers by holding up a ciborium containing the Eucharist. Two years after her death at age 59, she was canonized.

There are few actual records of her life: Several people testified concerning her holiness in order to establish her suitability for canonization. Clare seems to have written her Rule, her Testament, a blessing and several letters to her sister.

Thoman describes his book as a speculative, highly suggestive blend of biography and historical fiction and says it's almost impossible to write a biography of a woman born more than 800 years ago because women at that time stayed in the shadows.

But given the nature and accomplishments of the woman who is his subject, I had hoped for more.

Advertisement

Amy Tan says her father loved God more than he loved his wife, his two sons and his only daughter. What's worse, she writes in this telling memoir, "he would have [gladly] admitted that this was true."

An engineer and a Baptist minister, her father would have explained that the First Commandment required that one love God above all else. Besides, as he saw it, God's love was greater than what a parent could provide.

To compose Where the Past Begins, Tan rummaged through seven large plastic bins of memorabilia, including letters, newspaper clippings, and historical and family documents, as well as diaries and journals. Tan also includes emails between herself and her editor about the writing of this book — sections that tend to distract from her noteworthy family story.

The best of the book's six main chapters concerns Tan's parents, John and Daisy Tan, from their life in China to their marriage in the United States to the birth and raising of their three children.

Amy Tan in 2008 (Wikimedia Commons/David Sifry)

Growing up, Tan (born in 1952 in California) thought she knew her parents and grandparents, but learned through her research that her father and mother were individuals whose complex interior lives were difficult, if not impossible, to discern.

Her mother had a fierce temper and was suicidal. Her father believed he was divinely inspired to spread God's word — like Paul. When his firstborn became ill, John Tan adopted an Abraham-and-Isaac mentality and believed that God would intervene and spare his son at the last minute. When God didn't, Tan's father sprinkled his responses with Bible quotes that seemed to lack true feeling.

Tan felt that her father's reaction to her brother's illness and death lacked sincerity and was hypocritical. Tan also thought her father was "too busy appeasing God to notice his daughter." His love for God wasn't love, she says. It was fear based on guilt.

He had met Daisy in China and had fallen in love with her despite the fact that she was already married. Tan says that when Daisy left China (leaving behind her three daughters and first husband) to live in the U.S. with John, he felt guilty because he had committed adultery and would now have to live with the reminder of his sin. This, Tan suggests, is why he would fear God and confuse this fear with love.

His fear, though, made her reject the notion of a vengeful God that he advocated. Tan believes that fear leads to hatred and is the worst element of organized religions.

If her father were alive today, she writes, she would tell him that Jesus was crucified because of hatred, yet Jesus had advocated an uncompromising love of neighbor. His very life and death had signified that love.

And she would ask her father whether he honestly thought Jesus would want to put people in hell because they did not believe he sacrificed his life in order to save them. It's a good question in a sometimes-riveting book.

[Diane Scharper teaches memoir and poetry for the Osher Institute at Johns Hopkins University.]