Seminarian Renan Alberto Lima de Oliveira, 21, assigned to Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church in Manaus, Brazil, delivers a protective mask to a resident in one of the city's slums May 21 to minimize the spread of COVID-19. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

With more than 38,000 deaths caused by COVID-19, Brazil has the third-highest death toll in the world. While state governors and city mayors have imposed restrictions on many nonessential activities, President Jair Bolsonaro's administration has never imposed a nationwide quarantine, and the curve of infection has continued to grow.

Brazil's Catholic bishops have been working to raise awareness of the disease and to keep in place precautionary measures, despite the government's stance. In a series of interviews with NCR, several of the prelates described the challenges they are facing.

Since March, the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil has recommended the suspension of all Masses and other in-person celebrations, asking people to stay at home.

The bishops' firmness has generated many negative reactions, particularly among Bolsonaro's Catholic supporters and members of ultratraditionalist Catholic groups, which have been campaigning for the return of in-person Masses.

Now, many states and cities are reopening all activities — including religious services — but the Brazilian bishops have maintained a prudent attitude regarding both church life and the social organization of Brazil as a whole.

"I think the most reasonable way for the church to preserve the people's health, already so impacted, is to avoid the immediate return to in-person activities. We'll certainly be criticized, but we have to be responsible," Roraima Bishop Mário Antônio da Silva, the conference's vice president, told NCR.

Neurilene Cruz, a Kambeba indigenous nurse technician, conducts a COVID-19 test on Waldemir da Silva, 61, a Kambeba indigenous chief, in Tres Unidos, Brazil, May 21. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

Da Silva's diocese spans the entire state of Roraima, the northernmost and least populous state in Brazil, in the Amazon rainforest. The only public hospital in the state that has the capacity to treat COVID-19 patients, in the capital city of Boa Vista, is already overcrowded.

In the countryside, there are no intensive care unit beds, so all patients must travel to Boa Vista. "The basic infrastructure and logistical organization in our state don't allow us to go back to our activities yet," da Silva said.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Bolsonaro has advocated what he defined as a "vertical confinement," in which only members of groups at higher risk should stay at home. The main argument for such a policy has been economic in nature. Bolsonaro and his supporters have repeatedly rejected a broad suspension of commercial and productive activities.

"We know that the economy must be activated. But the biggest problem is that there's a confusion between economy and market. What many people really want is the market's reactivation. The economy should be in service of life, and not submitted to profit," da Silva argued.

The attitude of Bolsonaro and his supporters, along with a gigantic volume of fake news and misinformation concerning the disease on social media, has misled large segments of the population in regard to the necessary precautionary measures.

Advertisement

In five of Brazil's 26 states, the occupancy rate of ICU beds is higher than 90%. The health care system in several big cities has already collapsed. Bishops fear that the reactivation of the economy and social activities in many regions will cause a sudden deterioration of the situation.

"Two weeks ago, I was employing the term 'chaos' to describe such a hypothesis. Now, there's no other word than 'genocide.' That's the nature of the reopening policy in Brazil," Bishop Reginaldo Andrietta of Jales told NCR.

Andrietta, who leads the bishops' Workers Pastoral Commission, blames big businessmen and the financial market for pressuring the government to reopen the economy.

"Governors and mayors have been gradually giving in to such pressures, aligning themselves to the federal government. This must be said by the church. We must be clear about it and confront such state of things," Andrietta said.

The economic crisis produced by the pandemic, the bishop said, was intensified by the unfair economic policies of the Bolsonaro administration.

"A great part of jobs in Brazil are created by small employers. They don't have any support now, because the government preferred to inject money in banks and those funds never arrived as credit for the small companies," said the prelate.

While the authorities and big businessmen push for the end of confinement, the coronavirus keeps killing people, especially those of color and those without means.

The relative of a person who died of COVID-19 and funeral workers wearing protective clothing and masks carry the victim's coffin in Manaus, Brazil, May 7. (CNS/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

A recent study conducted by the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro analyzed 30,000 severe cases of COVID-19 and found that 55% of Afro-Brazilians who were hospitalized died, while only 38% of hospitalized white people died.

In São Paulo, the biggest city in the country, the study found, blacks have 62% more chance of dying of COVID-19 than whites do.

"To reopen the economy, as some governors and mayors are doing, is a big irresponsibility. This is a moment of taking care of the people," Archbishop Zanoni Castro of Feira de Santana told NCR.

Castro pointed out that the disease has been devastating for the black residents of impoverished neighborhoods throughout Brazil and for quilombola communities, rural settlements formed by the descendants of African slaves who fled captivity in colonial and imperial times.

"Many quilombola communities don't even have clean water. Prevention is already very difficult, so our focus should be on those vulnerable people," said Castro.

Andrietta, who has decided not to resume in-person celebrations while the number of cases keeps growing, said that the bishops have been discussing strategies to make church life more active — and that may include, depending on local conditions, partially opening church buildings for a larger number of churchgoers.

"There are different situations and contexts and each bishop has a style and a form of seeing things. We're all defending life and stimulating people to remain at home, but we're not paralyzed," he said.

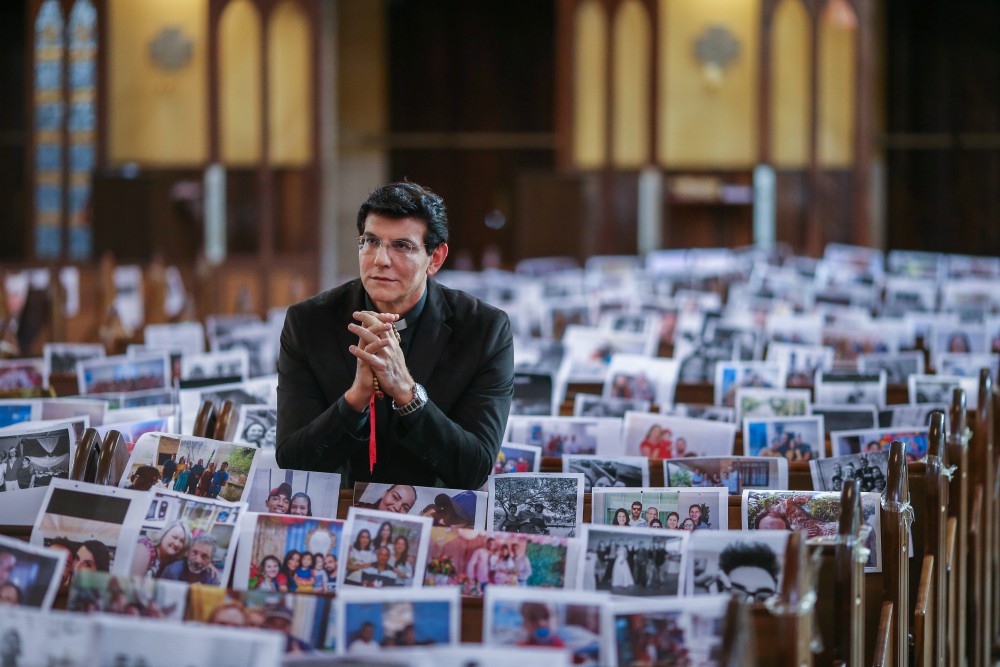

Fr. Reginaldo Manzotti prays during Mass with photos of his parishioners taped to the pews in the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Curitiba, Brazil, March 21. (CNS/Reuters/Rodolfo Buhrer)

A few dioceses partially resumed celebrations weeks ago, such as Goiânia, in Goiás state. The archdiocese decided to follow the local governor's determinations, and he allowed church services, so long as a number of safety precautions were undertaken.

"We have very strict protocols. People have to register at the church's secretariat in order to be allowed to go to Mass. Members of groups at higher risk are not allowed," Bishop Levi Bonatto told NCR.

Only Sunday Masses have been resumed for up to 30% of the individual church's capacity. People must take their temperature at the entrance of the church, use hand sanitizer, wear masks and keep distant from each other.

The bishops' conference has recently released a list of protocols to be followed by dioceses that wish to resume some of their celebrations. The procedures were inspired by the measures adopted by the Portuguese bishops and include recommendations for many kinds of church activity.

"That document doesn't mean that the [conference] is suggesting that in-person celebrations should be resumed. Each bishop must evaluate the conditions in his diocese," said Andrietta.

"A great group of us have been talking about how we can bring bigger groups to church in order to collectively reflect on our role in society at this moment," he added.

The serious social impact of the pandemic in Brazil has posed a set of challenges to the country's church. The bishops have been demonstrating that, amid the political polarization and the health care crisis in the country, Catholics still have a central role in the public debate and in the pursuit of ways to overcome the nation's problems.

"We know that we're not heroes, we're victims as everybody else," said da Silva.

"But we're aware of our role in defense of life, in defense of Jesus Christ's faith, and in defense of democracy and the common good," the prelate continued. "Those are the principles that have been guiding us in tormented times."

[Eduardo Campos Lima holds a degree in journalism and a doctorate in literature from the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Between 2016 and 2017, he was a Fulbright visiting research student at Columbia University. He has written for major news outlets, such as Reuters and the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S. Paulo.]