During a 2019 listening session on racism in Indianapolis, Bishop Shelton Fabre of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana, blesses a basket (held by Indianapolis Archbishop Charles Thompson) containing people's written accounts of experiences of racism. Fabre, who is chair of the U.S. bishops' Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism, was among a group of church leaders who were recently evaluated with Call to Action's anti-racism scorecards. (CNS/The Criterion/Sean Gallagher)

Despite global uprisings against police brutality and systemic racism, many U.S. bishops and cardinals have not spoken publicly about these issues, while others have yet to turn talk into action, according to the Catholic social justice organization Call to Action.

In December 2020, the organization's lobbying working group, led by John Noble, released a set of anti-racism scorecards for a "core group" of church leaders the group deemed important to the fight for racial justice both within and outside the Catholic Church.

Call to Action sees many bishops and cardinals as potential partners in a fight for racial justice.

Some U.S. bishops and cardinals "have spoken and acted prophetically about the need to dismantle white supremacy and racism," Noble said in a statement Dec. 19. "Others have work to do and have fallen silent when they should have spoken out."

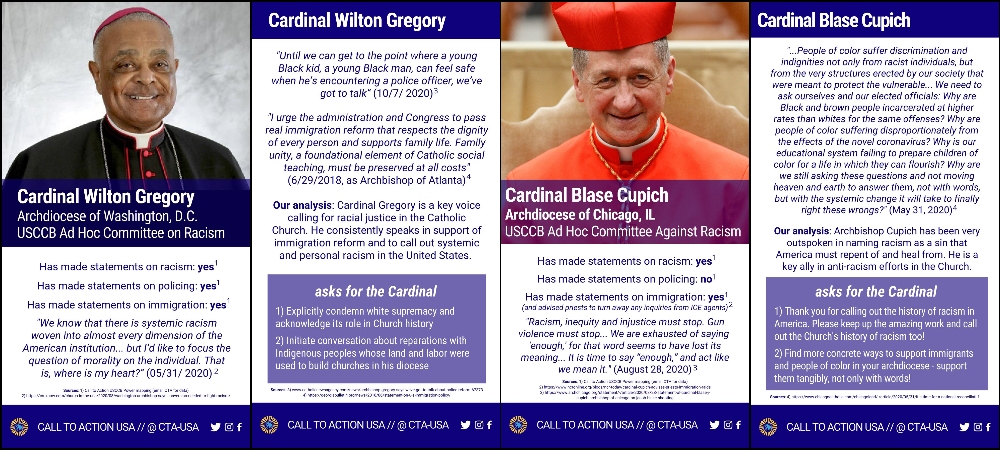

The scorecards track bishops' statements on racism, police brutality and immigration, highlighting important quotes and including steps parishioners can take to encourage their bishops to do more.

So far, the group has released scorecards for nine church leaders:

- Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago;

- Archbishop Gustavo García-Siller of San Antonio;

- Cardinal Wilton Gregory of Washington, D.C.;

- Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey;

- Archbishop Allen Vigneron of Detroit;

- Bishop Shelton Fabre of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana;

- Archbishop Thomas Rodi of Mobile, Alabama;

- Bishop Joe Vásquez of Austin, Texas;

- Archbishop Thomas Wenski of Miami.

Six of the nine prelates Call to Action has profiled thus far — Cupich, Fabre, Gregory, Rodi, Tobin and Vásquez — hold seats in the U.S. bishops' Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism. Wenski is on the conference's Committee on Migration, and García-Siller is part of several subcommittees within the Cultural Diversity Committee. Vigneron is the vice president of the conference.

Cupich, Gregory, Tobin, and Fabre earned high marks from the group. Rodi was criticized for not condemning white supremacy.

Nadia Busekrus, who coordinated the project, said she noticed that a few church leaders have actively worked toward racial justice, appearing at protests and pushing for policy change.

A protester is seen near the Capitol in Washington May 21, 2018, during an anti-racism demonstration. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Many others, however, in speaking about racism, have primarily called for prayer, self-reflection and "personal conversion."

Internal anti-racism work is important, said Busekrus, who is white.

"But then sometimes it would stop there," she said. "And there wouldn't be a call for systemic change, or policy change or any other additional action."

In his May 2020 statement on the police killing of George Floyd, Vásquez called for "a deep individual conversion of heart," and in September, Vigneron called for penance and the conversion of hearts to eradicate racist attitudes and behaviors. Neither one outlined specific steps his diocese would take to combat racism.

Bishops in cities from Pittsburgh to Denver to Seattle, as well as the chairmen of seven committees within the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, have made similar statements in response to Floyd's killing, naming racism as a sin and praying for peace and reconciliation, but offering few concrete calls to action.

In 2018, the bishops' conference released a pastoral letter on racism — its first letter addressing the topic in nearly 40 years. The letter discusses in broad terms the history of racism in the U.S. and offers a few gestures toward societal reform and increasing diversity within the church.

The document, however, fails to acknowledge many of the abuses perpetrated by the church itself, including a series of 15th-century papal bulls that legitimized global colonization and genocide; the Catholic residential schools that removed Indigenous children from their families and forced them to assimilate; the Catholic universities and religious orders that enslaved and sold Black people; or the white Catholic schools, convents and churches that excluded Black people well into the 20th century.

Instead, it includes over a dozen mentions of personal conversion or "conversion of hearts," and ends with a prayer, that "prejudice and animosity will no longer infect our minds or hearts."

Zach Johnson, executive director of Call to Action, said he's disappointed to see these kinds of sentiments — "Both sides need to come together, personal conversion, pray for everyone, pray for peace" — crop up time and again in bishops' responses to racism and police brutality, in lieu of plans of action. Johnson, who is white, called such statements "damage control."

"It's really important that bishops are talking about things beyond thoughts and prayers," Busekrus said. "Because ... as the leaders and, supposedly, shepherds of our church, they should be calling us to live as Jesus would live."

Call to Action's anti-racism scorecards for Cardinals Wilton Gregory of Washington and Blase Cupich of Chicago (Call to Action)

The purpose of the scorecard project is to help parishioners encourage their leaders to speak more strongly against systemic racism — embedded in laws, policies and institutions — and translate their principles into more tangible action, Noble, who is white, wrote in the statement.

"These cards and their research allow the laity to be informed about their bishops' public stances on racial justice, and they give the laity tools for lobbying their local bishop and building relationships in the struggle for racial justice," he wrote.

The suggestions for laity differ based on each bishops' previous statements and actions. Some of the scorecards praise bishops — including Gregory, Fabre and Cupich — for their previous statements, while encouraging them to go even further.

Some next steps for bishops include asking them to explicitly call out racism in the church, educate the faithful on the history of white supremacy in the U.S. or start conversations with the Indigenous peoples whose land and labor the church exploited.

Other Christian organizations, including several Episcopal dioceses and institutions, the United Methodist Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church have in recent years begun to acknowledge and apologize for enslaving Black people and take steps toward reparations.

In September 2020, the Minnesota Council of Churches formed an initiative to "address white supremacy and embrace truth telling in Minnesota." Its three-point plan includes a "truth telling process" to acknowledge "complicity by faith communities in racial injustice and disparities"; education and anti-racism training within each member church; and the formation of a coalition to fight for and deliver reparations to Black and Indigenous communities in Minnesota.

Shannen Dee Williams, who studies Black Catholic history as an assistant professor of history at Villanova University, has argued that the Catholic Church also owes reparations to Black Americans.

In an article for Catholic News Service, Williams outlined a plan for the church that included formally apologizing for the church's role in slavery and segregation, teaching Black Catholic history, investing in Black Catholic schools and churches, establishing scholarships for Black students at Catholic universities and fighting for anti-racist policies nationwide.

Advertisement

Busekrus and Johnson said Call to Action hopes to push the church and other Catholic institutions toward reparations, both for enslaving Black people and for displacing Indigenous communities.

"We're so far behind," Johnson said. "It's just an indicator of how reactionary and conservative so much of Catholicism [is], especially the leadership."

Johnson and Busekrus said parishioners whose bishops already have scorecards can use them to start encouraging their leaders to take the next steps.

"I think the relational aspect of this is so important," Busekrus said. "Not that it doesn't work when people outside of a diocese ask a bishop to do something, but I think it's even more meaningful when it's coming from within the diocese."

Those whose bishops aren't listed yet can help research their prelates' statements on racism by signing up for the Call to Action email list, which can be found at the bottom of Noble's statement on the scorecard page.

The group hopes to eventually score all of the roughly 270 active bishops in the United States, Busekrus said.

Johnson said he wants to see bishops and their dioceses collaborate with anti-racist organizations that are already working in their communities. And in their capacity as church leaders, they should start working on anti-racist initiatives within the church as well, he said.

Johnson said white Catholics like him who are engaging in anti-racist work in their communities need to remember that the work is an ongoing process.

Anti-racism is "not a to-do list, or a checklist or a project that you do," he said. "It's a way of life."