Children play on top of tanks on display in front of the Motherland Monument Oct. 31 in Kyiv, Ukraine. (AP photo/Bram Janssen)

When Britain's BBC ran a late November documentary about the mass deportation of Ukrainian children, it was only the latest of many grave accusations leveled against Russia since its brutal February 2022 invasion of the country.

And while information remains mired in claims and counterclaims, mounting evidence of another major war crime is stoking outrage, not least in Ukraine's Catholic Church.

"Children have been transported to Russia without consent from their parents and turned ideologically against Ukraine and their own families," Auxiliary Bishop Jan Sobilo of Kharkiv-Zaporizhzhia told NCR.

"Alongside the occupation, repression and injustice, this has inflicted yet another painful wound. While our own society can do little, the international community seems to lack motivation for forcing Russia to liberate the children and give them back."

The BBC film, tracing the fate of youngsters taken from Kherson and Mariupol when Russian forces took control of those cities, follows other reports on the deportations, which have left Ukraine overwhelmed with cases of missing children and fueled demands for action.

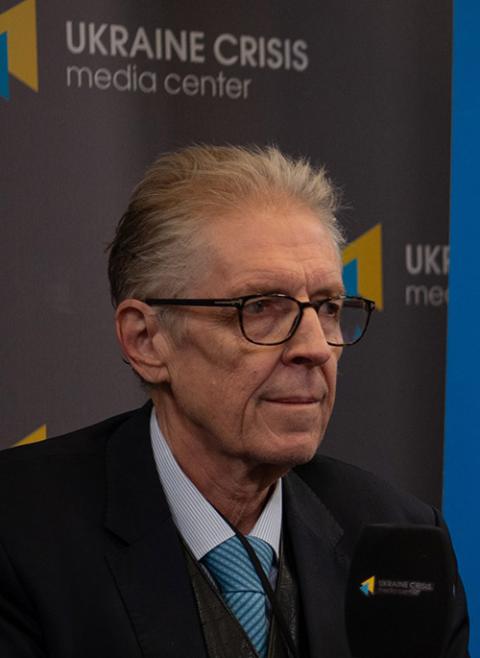

Auxiliary Bishop Jan Sobilo of Kharkiv-Zaporizhzhia (Courtesy of Jan Sobilo)

Within the film, a Kherson mother recounts how she saw her 2-year-old, Viktor, peering from a bus window on Russian TV, while a Mariupol teenager, Bohdan, who is now with a Russian foster-family, describes on social media how he now faces conscription into the Russian Army, after being told Ukraine had abandoned him. (Since the film's production, Bohdan has returned to Ukraine and reunited with relatives, according to recent reporting by The Associated Press.)

A 10-month-old baby, Margarita Prokopenko, was taken to Moscow for "medical rehabilitation," but later adopted under a new name by Sergei Mironov, a politician sanctioned by the West for his links to President Vladimir Putin.

Ukraine's human rights commissioner, Dmytro Lubinets, is investigating the case of the infant, now registered as Marina Mironova, a Russian citizen.

And while Moscow insists the children were relocated for their own safety, and will be returned if their parents or guardians submit legal petitions, the forced removals have been confirmed by the United Nations, while Ukrainian children have been shown at public rallies on Russian TV, tearfully thanking military officials for their "rescue."

Russian President Vladimir Putin gives a televised address June 24 in Moscow, Russia. (OSV News/Gavriil Grigorov, Sputnik/Kremlin via Reuters)

The child deportations are currently put at around 20,000 by the Ukrainian government, although the total is feared much higher, and formed the basis for war crimes charges brought last March by the International Criminal Court against Putin and his children's rights commissioner, Maria Lvova-Belova.

The two-year war has already left a highly provisional U.N.-documented death toll of 10,000 civilians, including over 500 children, with Western estimates of military casualties running close to half a million and tens of thousands of possible war crimes already reported.

"They've declared these crimes and issued warrants for the perpetrators, but there've been no consequences," another Catholic bishop, Stanislav Szyrokoradiuk of Odesa-Simferopol, told NCR.

"Though no one has any doubt that war criminals are active everywhere, nothing has happened. The U.N. and its agencies are doing little in practice and simply aren't effective in their humanitarian efforts."

Bishops Leon Dubrawskyi of Kamianets-Podilskyi and Stanislav Szyrokoradiuk of Odesa-Simferopol concelebrate an outdoor Mass Sept. 14, 2022, in Shargorod, Ukraine. The Mass was in celebration of the special day of prayer for Ukraine and the end of the Latin-rite bishops' Year of the Holy Cross. (CNS/Vyacheslav Sokolovy)

Repatriation of deported children forms part of Ukraine's 10-point peace plan, while a Ukrainian government website, "Children of War," offers detailed advice, with a 24-hour hotline, on how to report abductions.

Its work is supported by "Save Ukraine," a nongovernmental organization run by Mykola Kuleba, a former presidential commissioner for children's rights, who told "60 Minutes" in November that Russia's plan for the missing children was to erase their past and "destroy Ukrainian identity." According to Kuleba, they "brainwash them, indoctrinate them, Russify them."

Meanwhile, Ukraine's churches have also taken up the children's cause, offering shelter to others in danger in parish and monastic buildings across the country.

"Children of war are among the most vulnerable sections of our society — the real number who became victims of Russian violence due to abduction and forced eviction may reach tens, even hundreds, of thousands," Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, head of the Ukraine's Greek Catholic Church, confirmed in a national message last March.

Similar appeals have been made by the Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations, grouping Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant leaders, as well as Jews and Muslims.

Meanwhile, Pope Francis lamented the children's plight in a December 2022 pre-Christmas message, and discussed it during an audience at the Vatican in May with Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Pope Francis and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy meet May 13 in the pope's studio at the back of the Vatican audience hall. (CNS/Vatican Media)

When a Vatican peace mission was announced the same month, headed by Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, the return of abducted children and other Ukrainian prisoners was cited as its main purpose. Zuppi raised the issue when he visited Russia in June, holding talks with Lvova-Belova, the indicted children's rights commissioner, and Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill.

The cardinal also discussed the children's repatriation with U.S. President Joe Biden in Washington in July, telling Rome reporters he was seeking a "mechanism" to help them.

Cardinal Matteo Zuppi is pictured in a May 27, 2022, photo. (OSV News/Reuters/Yara Nardi)

Meanwhile, the fate of deported children has also been raised repeatedly by the Vatican's ambassador to Ukraine, Archbishop Visvaldas Kulbokas, one of very few foreign representatives remaining in Kyiv throughout the war.

Sobilo says he's hopeful that the Vatican's efforts will achieve results.

His eastern Kharkiv-Zaporizhzhia Diocese includes the occupied and largely destroyed cities of Mariupol, Melitopol and Berdyansk, as well as the northern towns of Kupyansk and Izium, from where children were also taken.

Although Catholic families have been affected, Sobilo told NCR, many parents are too afraid to speak openly about their lost children, fearing Russian reprisals.

"The Russian aim is to frighten, divide and silence people, by suggesting more children will be taken away if they criticize Russia," the auxiliary bishop told NCR.

"But people from many backgrounds are asking the Holy Father to exert his influence in bringing these children back from captivity to their families," said Sobilo. "I'm confident the Vatican is doing what it can with the Russian government."

To date, it's unclear how many children, if any, have been returned thanks to Vatican efforts.

Krzysztof Janowski, Kyiv spokesman for the U.N.'s High Commission for Human Rights (Courtesy of Krzysztof Janowski)

"We don't have any presence in Russia or occupied areas of Ukraine - so the situation is complicated and there are no complete figures," Krzysztof Janowski, Kyiv spokesman for the U.N.'s High Commission for Human Rights, told NCR.

"There were cases in which parents were allowed to go to Russia to pick up their kids," he said. "But we don't know how accurate the information is, and we've no comprehensive overview as to how many children might have been taken."

With over 4,100 schools destroyed or damaged during the war, according to Ukrainian government data, and tens of thousands left without proper education, Ukraine's children are among the war's greatest casualties.

Meanwhile, Ukraine's government says barely 400 of the thousands of abducted children have so far been returned, and has invited Holy See representatives to attend an international Kyiv conference on the missing children later this month.

In Odesa, Szyrokoradiuk is thankful his own diocese warned parishioners early on to safeguard their children, and not to accept Russian offers to have them taken to places of rest and safety in Crimea and other areas outside Ukrainian control.

Advertisement

While the church prays for those now missing, he believes the advice saved many Catholic families from tragedy and bereavement.

Sobilo said that at least no one will any longer believe Russian propaganda about happy Ukrainian children thanking Moscow for their new life.

"What we can say for certain is that war has its own rules — whether in the 21st Century or previously, it unleashes the lowest, most primitive instincts, bringing murder, rape and debauchery, and a capacity to inflict suffering which would be unimaginable in peacetime," the Kharkiv-Zaporizhzhia auxiliary told NCR.

"Despite everything, we hope the international community will condemn these abductions and deportations with a united voice," he said. "If the whole world does so, there's still a chance these children could be released."