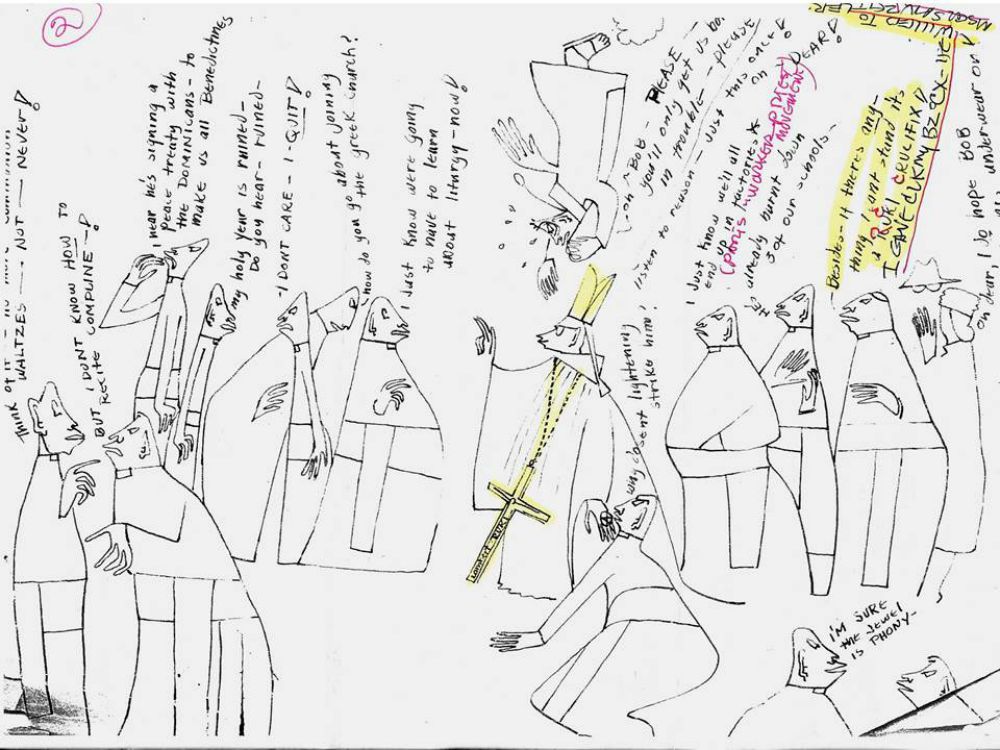

Illustration by Robert E. Rambusch (Collection of the author)

In their guidelines for parishes building or renovating a place of worship, Built of Living Stones, the country's Catholic bishops note the value of retaining a "liturgical consultant," a somewhat clumsy label for a design professional responsible for helping faith communities through the pre-architectural planning and education likely to make their efforts most fruitful.

By explicitly recognizing the place of liturgical consultants in the renewal of Catholic worship and art as it continues to play out at the parish level, the American bishops are confirming merely that the typical church-building project in our time is a "team effort" involving more than pastors, architects and contractors. If lay parishioners are to contribute with more than their dollars, they must first be instructed how to do so.

Among the early pioneers of the practice in the years immediately following the Second Vatican Council was Robert E. Rambusch, the eminent graphic artist and church designer born of the well-known, New York City-based family of ecclesiastical artists, who passed away this spring at the age of 93.

Rambusch and his contemporaries — Frank Kacmarcik, William Schickel, Adé Bethune and Ed Sövik (see his obituary for more information) — represent a generation of Christian artists animated by the ideals of the modern Liturgical Movement and trained following World War II at the great centers of sacred art throughout Europe.

I personally learned of Bob Rambusch's death while preparing to deliver a conference paper proposing ways to bring the designs of Catholic churches more in line with the theology underlying Pope Francis' recent Year of Mercy. An early-morning phone call from a mutual friend roused me from my hotel bed to the news that Bob had died and that my name appeared on a list of "Erie, Pennsylvania Friends" discovered among his possessions. To have included me in such company was characteristic of Bob, who hardly needed to maintain anything approaching friendship with a professional acquaintance more than 30 years his junior from a place as far removed from the world surrounding his long-time business address at One Fifth Avenue in Manhattan as one could imagine.

Advertisement

We had met in the mid-1980s, after Bob was selected by the then-bishop of Erie, Michael J. Murphy, to lay the groundwork for renovation of the local cathedral church, a structure earlier gilded and stenciled by the Rambusch Decorating Company during what Bob what called "my grandfather's Celtic seaweed phase." Owing to significant popular opposition, the project foundered, but not before I, a young university professor with a bourgeoning liturgical consultancy of my own, learned of how Catholics can go about breaking the Ninth Commandment in the name of defending their view of the Fourth.

Bob's smartly-tailored suits, large-brimmed hats and unshakable, New Yorker accent didn't fly well with the local crowd, not to mention his briefcase-load of cockamamie ideas about "a new kind of liturgy needing a new kind of architecture" that made people's heads spin. Bob's considerable professional attainment, which included oversight of some 400 building projects nationally, did little to impress the hecklers drawn to a string of "listening sessions" hosted by the chancery, which took on the flavor medieval bear baiting. Thus, in short order, Bob was sent packing — a small wrinkle in his project schedule, I assumed, which freed him to move on with greater success to one of the 24 other cathedral projects that thickened his curriculum vitae.

To be sure, Bob himself could be irascible, combative and impatient with people whose opinions on the church's affairs proved as empty as their collection envelopes. ("You can't have a liturgical conscience," he'd quip, "without a social one.") He didn't suffer fools well, and there was much he found foolish and foolhardy in the church to which he clung.

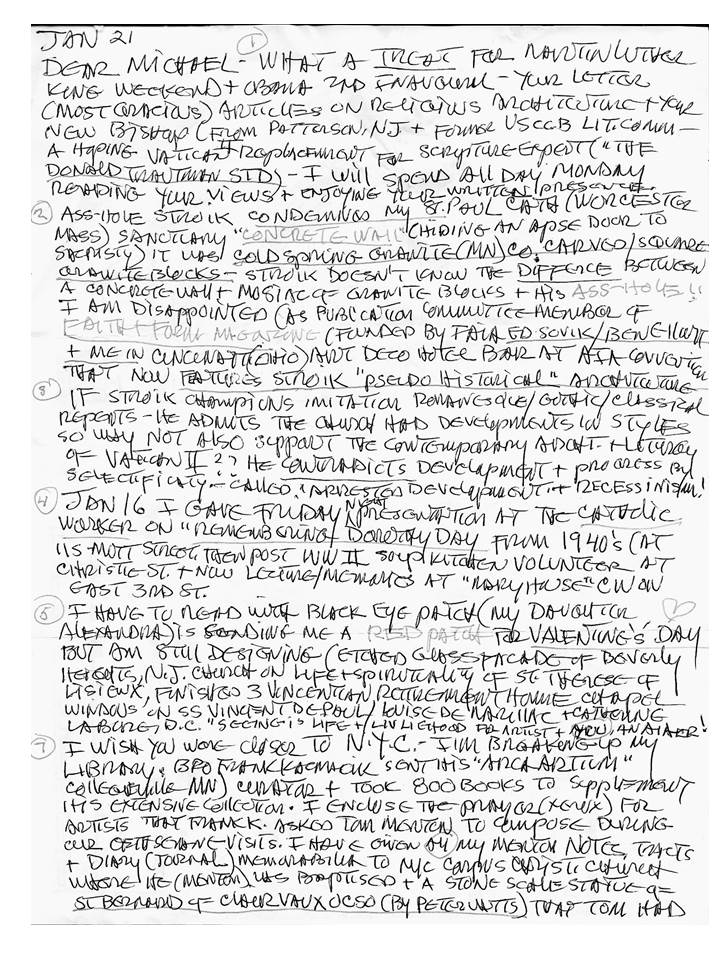

Letter from Robert E. Rambusch (Collection of the author)

What I'll remember most about Bob, however, aren't the local skirmishes connected to the church's larger "Liturgy Wars" his presence attracted to the shores of Lake Erie, or the professional reputation, or even the 1,000-watt neckties. Instead, it'll be his childlike familiarity with Mystery — a quality essential to anyone rehearsing the part of prophet or artist — along with a knack for generosity that extended to the countless bit players in his life, like me, whom he'd met through one church-building project or another. How he was able to keep up the flow of correspondence directed my way — invariably scrawled on the backs of drawings or dog-eared photocopies of his artwork for "The Catholic Worker" — still baffles me no less than how, given Bob's "scribble-even-in-the-margins" version of handwriting, the things ever made it through the postal system in the first place.

Having lost his wife Nancy to cancer in 1994 and, more recently, the use of an eye, Bob could have skimped on his very public persona or the thoroughly private stream of epistles he kept sending me. The pontificate of Benedict XVI had been particularly hard on him, as he watched Rome's rolling back of so many Vatican II-era liturgical advances in the name of "reforming the reform." He likewise fretted over the re-popularization within certain Catholic circles of the idea that church architecture was best when dressed up to look old-fashioned, something his cohort of consultants had tried hard to counter. "The imitation Classical/Romanesque/Gothic designs of the 'pseudo-traditionalists' prove they understand development in sacred art," he wrote me recently. "So why can't they accept modern developments?"

For Bob, a living church could not abide in itself or its art what he called "arrested development," which blinds it to the mischievous indiscretion with which the Spirit moves through history to inspire both art and prayer. What he hoped to devise for the parish-clients he served were settings firmly situated in the modern world and reflective of its prevailing mode of artistic expression. To that end, he could be ruthless in the way he'd go about stripping a place of the chalkware Catholicism that had comforted its users for decades. Nevertheless, what he leaves us by way of those blocky, uncompromisingly Minimalist altars or candle stands he was so fond of designing is a body of religious art as true to its time as it was the temperament of its flawed but faith-filled maker.

Bob's mark on post-Vatican II church architecture cannot be overestimated. Neither can the beauty of his work, as spare in its expression as any plainsong melody and as stubborn as the Gospel.

[Michael E. DeSanctis is a professor of fine arts and theology at Gannon University in Erie, Pennsylvania.]