An Italian family watches Pope Francis' March 27 "Urbi et Orbi" blessing on television. (CNS/Reuters/Marzio Toniolo)

Catholic parishes across the world are closed. Millions of Catholics have been unable to physically take part in the celebration of the Mass for weeks, and may not be able to again for months.

Simply put, the coronavirus pandemic is fundamentally changing how we do and be church.

What could these changes mean for us in the long-term? How will they affect us in the years to come, well after the initial threat of the pandemic has passed?

Over the past week, NCR surveyed two dozen theologians, social directors, non-profit leaders and pastors, asking them each to consider these questions. We're presenting the answers over the next three days.

Yesterday, we focused on questions of community. Today we turn to questions of church governance. Tomorrow, we'll focus on the church's social mission.

Massimo Faggioli, professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University (Provided photo)

Virtual liturgies run risk of 'de-localization'

Massimo Faggioli is a professor of historical theology at Villanova University.

The forced virtualization of liturgical space during this pandemic runs the risk of a new kind of centralization and de-localization of the Catholic Church.

In previous centuries, existential threats to the fundamental dynamics of ecclesial life gave advantage to the central level, that is, to the papacy.

We have seen how this works in Pope Francis' March 27 Urbi et Orbi blessing: the marvelous stage of Rome being used to its full potential. This does not look too threatening today, thanks to Francis' attention to the need for balance between the central and local levels. But this is an issue for the church in the long run because there is already an ongoing process of de-localization in our lives.

There is an ecclesiology — conscious or unconscious — behind the way liturgies are being adapted in this extraordinary time. It is not just a matter of technology. It is also a matter of ecclesiological reference in this time of suspension, looking forward to the time after the pandemic: Are we taking part in the liturgy of our local or "natural" community (the way it should be), or of our chosen ecclesial movement, in a dynamic of competition not very different from how the free market works?

This move away from the local to the centralized — whether the "center" is the Vatican or your self-selected, customized ecclesial group — will have an impact on the balance within the church: in terms of how we think about ecclesial structure and authority, but also in terms of institutional and financial sustainability for local churches.

The lack of ecclesiological awareness of this issue in the official guidelines for this liturgical emergency could be rife with long-term consequences, distorting the healthy ecclesiological balance between the different levels in the church.

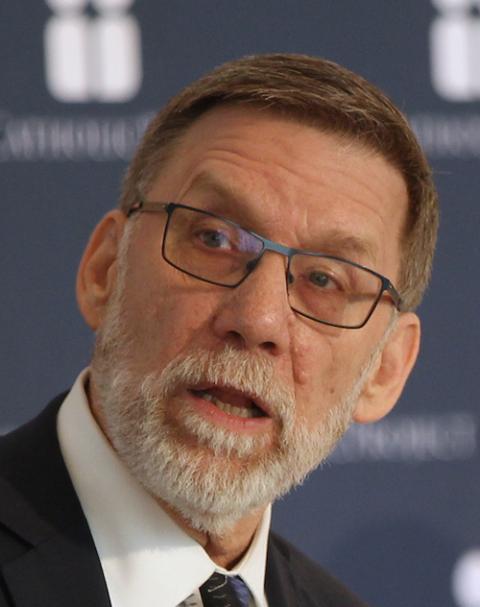

Richard Gaillardetz (CNS/Bob Roller)

Crisis, a specialty of the church

Richard Gaillardetz is the Joseph professor of Catholic systematic theology at Boston College and a former president of the Catholic Theological Society of America.

Global crises of the kind we are currently facing can lead to seismic changes, but often as not, they simply clarify current challenges and possibilities. Certainly, the widespread cancellation of public religious activities has had a palpable impact on church life. When the pandemic has passed, perhaps many Catholics will simply not return, but I have my doubts.

This past Sunday, my wife and I participated remotely in our parish's livestreamed Mass. We were grateful for the opportunity and heartened to see so many parishioners joining us in virtual community. Our pastor and pastoral team are to be commended for their creative efforts to reach out to parishioners in this and many other ways. However, I don't think we were alone in perceiving both the opportunities for, and limits of, virtual community. Dare we hope that this fast from the eucharistic table, fueled by the exigencies of the moment, might upon our return rekindle a heightened eucharistic consciousness?

This pandemic has highlighted the importance of certain characteristic Christian practices. Pope Francis has exemplified the pastoral leadership we need as he invites us to a kind of "solidarity in place," encouraging us to check in on friends and family by phone or internet, or to deliver groceries to those in need. His lovely Urbi et Orbi blessing March 27 offered the consolation and encouragement we need from our spiritual leaders. And, although a few clerics have succumbed to a troubling sacramental romanticism, most of our pastoral leaders have wisely embraced draconian restrictions on public worship, integrating a Catholic sacramental consciousness with an equally Catholic commitment to the common good.

This pandemic will doubtless have a lasting effect on the church, but it is worth recalling Timothy Radcliffe's observation that, for Catholicism, crisis is la spécialité de la maison, "the specialty of the house."

Advertisement

Accompanying sisters in more creative ways

Sr. Sally M. Hodgdon is general superior of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chambéry and a former vice president of the International Union of Superiors General.

The coronavirus pandemic has literally stopped us from our usual routine of close physical presence. As leaders of international congregations of women religious, we travel much of the year. This crisis has offered us the opportunity to lead and accompany our sisters in more creative and, actually, more efficient ways. Use of social media and online participation in global committee meetings has been part of our life for some years, and now during the pandemic, it is the "new normal" both personally and communally.

Development of broader networks through social media and more use of online technology for individual and group meetings should continue even after all travel bans have ended. These allow for greater support and participation, with the voice of the larger community heard and their faces seen, as we discuss the common good and our future challenges. Certain rules, bylaws and canons will need to be amended, in both civil and canon law to allow for regular online board meetings.

Meeting our sisters face-to-face and coming to know their reality will always be valued and necessary. This pandemic has called us anew to balance this value with our deep commitment to live Laudato Si'. Our lack of travel has offered respite for our polluted atmosphere. So we will continue seeking creative ways to have meetings that allow us to offer hope, compassion, challenge and support to our members and at the same time align with our choice to work against further climate change, even in the post-coronavirus era.

Sr. Sally Hodgdon, superior general of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chambery, leaves a session of the Synod of Bishops on young people, the faith and vocational discernment at the Vatican in 2018. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Value what is essential

Natalia Imperatori-Lee is professor of religious studies at Manhattan College in the Bronx, New York, and the author of Cuéntame: Narrative in the Ecclesial Present.

We would all be dead if not for the grocery-store stockers. The farm workers. The maintenance staff. The nurses, the intake staff at hospitals and doctors' offices. Without the tech support people. The novel coronavirus has cast the mighty from their offices and lifted up the dignity and irreplaceability of those we thought were lowly workers.

In more ways than I could have imagined, our present crisis has revealed what is essential. Our confinement and anxiety have also revealed how much of what we thought was essential to our well-being was actually ancillary, or even detrimental. How will this new view of the essentials affect the church?

As the majority of parish staff are women, we should recognize that COVID-19 has revealed the essential, invisible work of women and of feminized professions: teachers, nurses, maintenance staff. What parent will take for granted a teacher's role in keeping their children on task, engaged and working toward a goal, much less in doing this for a group of 30 kids at the same time? How can we ever thank the (mostly Latinx, at least in New York City) cleaning staff who keep our public spaces sanitized, at great risk to their health, after the stress of disinfecting our doorknobs, washrooms, car doors or handbags?

Theologian Natalia Imperatori-Lee on the curial reform: "To separate out governance or administration from orders means that orders is primarily a sacramental ministry and that governance then belongs to the whole people of God, which is as it should be." (Provided photo)

These workers should make a living wage whether they work for the church or outside of it. They should have access to healthcare and childcare and all those things that human dignity demand. And that includes the church's own workers, especially the essential ones: the (immigrant) housekeepers and cooks, the parish secretaries.

My hope for the church as it emerges from the era of COVID-19 is that we rediscover and learn to value what is essential to the faith: the work of women, the value of honesty, transparency and expertise, the provisionality of all our knowledge, the working of the Spirit in unexpected places. And then, that we hold our religious leaders to these essential standards.

Abetting impulses already present

Jesuit Fr. Mark Massa is the director of the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life at Boston College.

The COVID-19 pandemic joins a much longer list of cultural, religious and ecclesiological issues that challenge the practice of Catholic Christianity in North America in the past several decades.

For example, the widespread replication of essentially political monikers to define what "kind" of Catholic one wants to be today have joined the older, simplistic notion of whether a Catholic is “lapsed” or not. This insistence on using qualifying language to define one's Catholicism from the get-go is something new and disturbing.

One can now be a "John Paul II Catholic," or a "Pope Francis Catholic"; an "orthodox Catholic" or a "Catholic Worker Catholic"; a traditionalist Catholic or a social action Catholic -- monikers placing one on a sliding left-right political kind of scale. It represents an assault on what "Catholicism" means both literally and ecclesiastically. As Mircea Eliade once observed, "the opposite of 'Catholic' is not 'Protestant,' but rather 'sectarian.'"

Add to this the widespread disaffection caused by the clergy sex abuse scandal, which has demoralized both laity and clergy, and has made the church's presence and teaching seem hypocritical to young people.

While the virus, by itself, will not cause a significant challenge to being a practicing Catholic today, in conjunction with the political splintering, disaffection caused by the clergy abuse scandal and widespread distrust of the institutional church on the part of young people, it has every possibility of abetting impulses already present within the community.

Stephen Schneck (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Hunger for understanding

Stephen Schneck is the executive director of the Franciscan Action Network and a former long-time professor of politics at The Catholic University of America.

The experience of COVID-19 has heightened the consciousness and reawakened the conscience of the church to the fragile, incarnate reality of human life. The church, like the whole world, has also been reminded by our experience of social distancing that human life can only be fully human when lived in solidarity and community with others.

What that means for Franciscan Action Network is somewhat unclear as yet, but something is occurring. There is an intensity to be noticed in support for both our social justice advocacy work and our faith outreach. Moreover, our sister faith-based social justice organizations are reporting a similar intensity among their supporters. Concern for the needs of others, especially for those unable to fend well for themselves in this time of crisis, is rising everywhere. So, too, are both calls for practical action and calls for spiritual nourishment.

Perhaps the newfound appreciation of solidarity and community is partly to be credited. There is now a realization not only of community but also of how important community is for our formation as human persons and a realization that social action is how communities themselves are formed and reformed. Organizations like Franciscan Action Network mobilize for that. But equally part of this rising support for organizations like mine is the heightened spiritual hunger of this moment. In times of plague, the hunger for understanding the meaning of life is sharp. I believe social action is revealed to be part of that meaning, but so too — and very profoundly — is faith.

It may be that our church's mission for our times is evident in this, too. Unmistakably, that's been Pope Francis' vision for the church.

C. Vanessa White, associate professor of spirituality and ministry at Catholic Theological Union at Chicago (Courtesy of C. Vanessa White)

Grace in a moment of fear

C. Vanessa White is assistant professor of spirituality and ministry at Catholic Theological Union at Chicago.

"The first thing I am going to do is hug everybody!" These words from my 86-year-old mother speak simply and eloquently of what life will be like for many in the African American community when we journey through this season of COVID-19.

We have longed for the sense of touch during this time of physical and social distancing. But we are not unfamiliar with living in times of great trial. We have journeyed through enslavement, Jim Crow, the terrors of lynching, racism, the Great Depression, shuttering and closing of Catholic schools and parishes, Black Lives Matter and the terror of 9/11.

Two common phrases from the Black religious tradition are that "God will make a way out of no way," and, "Trouble don't last always." Both speak to African Americans' belief that in the midst of fear and terrors of death, there is hope.

As we set our table with candles and join our pastor on our laptop or our bishop on TV on Sundays, we acknowledge those times within our history when we were denied access to full participation in Sunday Eucharist because of the color of our skin. The sense of exile, in many ways, strengthened our commitment to our faith.

As we no longer have access to the physical bread and wine, Body and Blood, we have come to reflect on what does it truly mean to be a part of the Body of Christ? The Scripture in 1 Corinthians 12: "If one of us suffers, we all suffer, and if one of us is uplifted we all share in the joy" has new meaning during this season of COVID-1 9.

This time of trial attests not only to the spirit of persons of faith, to make it over to the other side, but also to the creativity of our sense of church. This is a time of great fear, but it is also a moment of grace, as we journey forward, forever changed as a church.

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR's national correspondent; Michael Sean Winters is a longtime NCR columnist; Joshua J. McElwee is NCR's Vatican correspondent.]