Pastoral minister Martha Ligas lights the paschal candle with "new fire" during the 2023 Easter Vigil at the Community of St. Peter in Cleveland. Pastor and administrator Bob Kloos holds the candle. (Peggy Turbett)

Editor's note: According to a 2008 Pew Research study, one of 10 U.S. adults is a former Catholic. Some have moved on to other denominations, others have no church affiliation at all, still others have formed their own communities of former Catholics. In the final three parts of his five-part series, former NCR editor Tom Roberts looks at three different independent Catholic communities — how they came to be, and how they sustain themselves apart from the institutional church.

The Community of St. Peter might reside outside the boundaries of the Roman Catholic Church, but it feels close enough ties that it went through a "synodal" process and addressed a four-page final document to Pope Francis.

Much of the document combines the 12-year history of the community with aspirational projections for itself and the institutional church.

The document is one item in a drop-down list on a website where the most noticeable button, large and in the upper left-hand corner, reads "Pastor Search."

Life in community in the Catholic diaspora is always a mix of old and new, of familiar tradition and experimentation. Synodality, said the current pastor, Robert Kloos, one of the community founders and formerly a priest of the Cleveland Diocese, seemed compatible with the way the community operates.

From its beginnings, the Community of St. Peter was a project determined by discernment and democratic processes.

In closing 50 parishes, Bishop Richard Lennon let the congregation of St. Peter's Church know in March 2010 that in six months it would shut down. Unlike other parishes that were given a merger option in downsizing, St. Peter's was simply told it would close and that parishioners would have to choose one of two other possibilities.

At the time, the parish had the reputation of many "destination" parishes, those that are distinctive and pull people in from beyond geographical boundaries. It was a vibrant place with significant ministries in the inner city, a pastor who had a reputation as a compelling homilist and liturgist, and a vaunted adult education program that often brought in theologians, writers and others from outside the diocese.

In the words of one parishioner at the time, the bishop "underestimated us at every turn. ... We told him the building belonged to him and he could do with it what he wished, that we will live in the hope of the Resurrection."

The sentiment is familiar to the three communities profiled in this series and, no doubt, others. That outlook raises interesting questions: What constitutes a parish? And how important is a community to the understanding of parish? While fiscal and logistical realities might dictate changes, can a community simply be told to disperse because the diocese has a downsizing program underway?

Armand Accordino, a Habitat for Humanity employee and member of the Community of St. Peter, and pastoral minister Martha Ligas strip wallpaper for a Habitat rehab in March 2022. (Megan Dull, SND)

Fr. Robert Marrone, the pastor at the time who decided to go with the community and was ultimately excommunicated by Lennon, outlined the distinction between, for instance, a break with the institutional church over doctrinal issues, and one involving violation of people's rights by authority.

"This is not doctrinal in the deepest sense," he told this reporter in 2012, during his term as pastor of the community. "I am not denying the divinity of Jesus or the Trinitarian formulas," he said.

"I don't mean to be histrionic, but, no. I'm not going to the back of the bus. I'm not going to do this," he said, referring to the order from Lennon.

"I cannot agree to what you've decided to do. It's wrong. People's rights were violated. The rights of the people of the body of Christ were violated. The right to be together. They were not in danger of falling apart. No criterion [on which the closing was based] was genuine."

Advertisement

What is clear in U.S. Catholicism is that the culture of a parish, sometimes established over decades, is fragile at best. Examples abound of parishes, like the three profiled in this series, forced into difficult decisions by a bishop for a variety of reasons or, as in many other cases documented in NCR's pages, by the arrival of a new priest.

Marrone retired as pastor in 2017 and was succeeded by Kloos, who had been a seminary classmate and a priest of the diocese for a number of years before leaving to get married. Kloos recently announced his desire to retire, so the community is doing a national search for a new pastor.

In an interview, Kloos noted that when the community began the search for Marrone's replacement, an ordained male was high on the list of preferences. He said in a poll of the community regarding the current search, ordination was important to only 8% of the members. It is not even among requirements listed in the job description.

If there are no doctrinal disputes, as Marrone argued, there have been significant departures over time involving matters of theology and practice. One came to light recently when both Kloos and Marrone were going to be unavailable over a weekend.

What about the Eucharist? Who would say the words? The discussion that ensued took the community into some deep theological water.

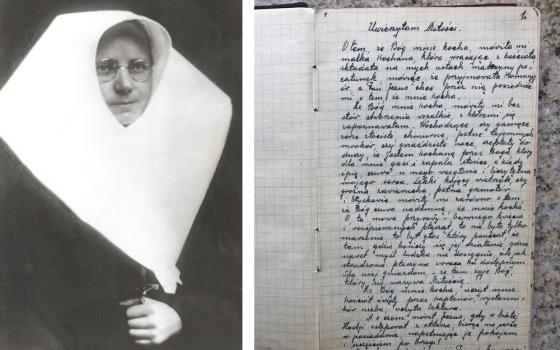

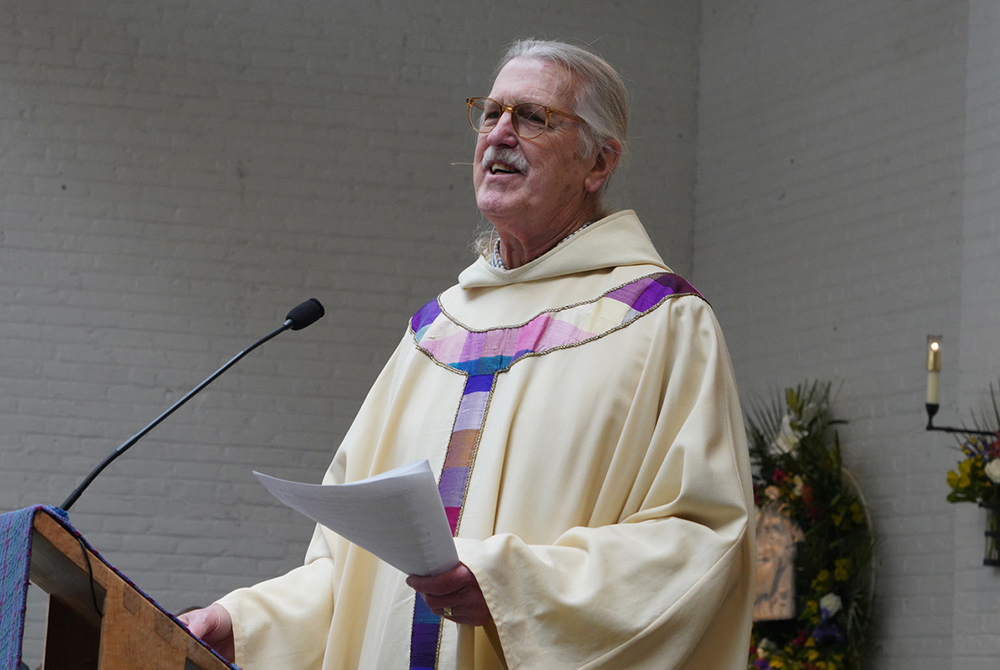

Bob Kloos, pastor and administrator for the Community of St. Peter in Cleveland, speaks during an Easter liturgy in 2023. (Peggy Turbett)

As Kloos related it, one person asked, "Why can't we continue with the eucharistic prayer and have a Communion service the way we do every week?", even though neither ordained minister would be present.

The issue was brought to the board, not so much as a policy question, Kloos said, but rather a bulletin about what was going to take place.

Kloos wondered: "Can we get to the point where we as a community can say we don't have to scurry to find someone who's ordained" if one of the ordained ministers isn't available?

In musing aloud about the question during an interview, Kloos continued: "What makes the eucharist a reality on this table? It's not the canon law, it's not the sacramentary, it's not the canonical component of the ritual. It's got to be the intention of the people who gather, recalling that Jesus said, 'When you want to remember me, do this.'

"Sixteen hundred years ago, the church said to all the people who were experiencing domestic church, 'Here, let me do that for you.' And literally took it out of the hands of the people. ... And then all of a sudden it was put only into the hands of those who were designated as worthy."

Members of the Community of St. Peter take part in the "Pride in the CLE" march in Cleveland on June 3. (Megan Dull, SND)

Whether Kloos will find mainstream theologians and historians who agree with him, the questions about the nature of the Eucharist and how parishes will remain eucharistic communities will continue to surface in the institutional church, not so much at first as a theological question, but as one dictated by demographics. As the numbers show, the population of priests continues to decline below the number of parishes in need of priests, and that downward trend seems to be solidly in place for the foreseeable future.

Kloos dispels the idea that there is something "magical" about anyone who presides at a Eucharist. The discussion is intrinsic to an independent eucharistic community.

He said that he and others are "trying to gradually help people understand that this is a community action. This is not Bob stepping in. It's not about the words of consecration. It's about the intention of the people who gather on Sunday."