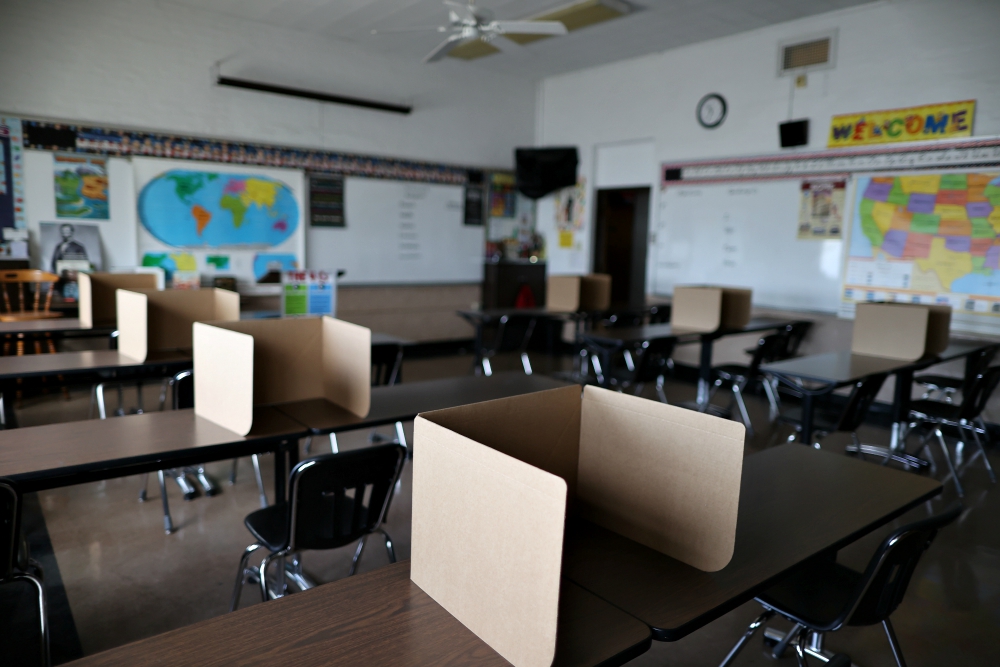

Social-distancing dividers for students at St. Benedict School in Montebello, California, are seen July 14. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

Never has the phrase "back to school" taken on such life-or-death connotations. Instead of shopping for pencils and notebooks, students this year are stocking up on hand sanitizer and face masks — school supplies meant to help keep them from acquiring the coronavirus if they head back to the classroom.

If they head back to the classroom.

In late spring and early summer, a number of schools — most publicly, the University of Notre Dame in a New York Times op-ed — predicted that school would open normally by fall.

But by the official first day of summer, coronavirus cases were surging, primarily in the South and Southwest, and by the time July Fourth's flags and firecrackers were packed away, many school districts had to walk back those plans for a normal reopening.

Now some are hoping for a "hybrid" model, in which students attend school for some days of the week and learn remotely at home on others. An increasing number are moving to completely online education, at least for the beginning of the year.

What's still unclear is how it will all work. Will students actually keep masks on all day? Will students with accommodations for learning disabilities face even greater challenges? Will socially distanced recess be any fun?

And how will all involved cope when — not if, but sadly when — a student, a teacher or someone else in the school tests positive, or, God forbid, dies?

Moving to all-remote learning raises questions, too. Will it be more substantial than the stopgap online learning of last spring? Have teachers been properly trained to facilitate virtual learning? Are parents of younger children available to supervise it?

Advertisement

Teachers are understandably anxious, worried about students' safety and quite frankly about their own. Meanwhile, school administrators — especially at nonpublic schools, including Catholic ones — are concerned about their institution's financial health and even survival.

There are no pain-free options here, though it must be acknowledged that we, as a country, could be in a better position by now if our government leaders had taken the virus more seriously in the earlier months.

Decisions on the ground are changing daily, but a pattern has emerged of private schools being more amenable to opening for in-person classes than public ones. The Los Angeles Archdiocese originally announced plans to resume in-person instruction after the area's public school district said it was moving classes online. But the archdiocese later had to switch to all-distance learning after spikes in coronavirus cases triggered state requirements to move online.

Some parents with the financial means are pulling their kids out of public schools and moving them to private — including Catholic — ones where they believe there is a better chance at in-person learning, reports The Washington Post.

Public schools do not face the same financial structure as tuition-dependent ones, and their teachers and staff have unions to help argue for their health and safety. It seems incongruent that Notre Dame announced it will not host the first presidential debate in late September, but the university is still planning in-person classes and football players are holding voluntary workouts for a yet-undetermined season.

Catholic schools should be leading the way in modeling pro-life values that put people's health, safety and lives first. Let's not put teachers, staff and students on the front lines of this pandemic.