Pope Benedict XVI walks down steps after giving a talk at the conclusion of a Mass for the Knights of Malta in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Feb. 10, 2013, two days before he announced his resignation. The retired pope marks his 92 birthday April 16. (CNS/Paul Haring)

We are living in a unique moment in church history with an ex-pope, properly credited for having the courage to resign when the problems he faced became overwhelming, living within the Vatican walls. The resignation is best interpreted as Benedict XVI's act of generosity toward the church. The graciousness Francis has displayed toward his predecessor is equally an act of generosity.

Increasingly, however, Francis must also be calling on the virtue of patience to deal with the interference of a predecessor whose retirement has gone from a promised "life dedicated to prayer" to a life of backseat pontificating.

The most recent – and perhaps most unfortunate – intervention was Benedict's letter theorizing on the causes of the sexual abuse crisis and, of course, defending his role in dealing with it.

That the latest was not a one-off, but part of a pattern that was pointed out by NCR Vatican Correspondent Joshua McElwee in reporting on the letter.

In November 2016 a book-length interview was published in which Benedict defended his eight-year papacy, saying he didn't see himself as a failure. In March of that same year he inserted himself into a Francis initiative when he did an interview in which he expounded on God's mercy while Francis was in the midst of an Extraordinary Jubilee Year, with mercy as its central theme. These interventions may appear anodyne to some, but they set a terrible precedent, making the perception or reality of a rivalry between the former pope and his acolytes and the incumbent pope and his supporters more likely.

Benedict's latest interjection landed within shouting distance of a recent and first-of-its-kind international gathering of bishop leaders from around the globe to discuss the abuse crisis and seemed, unlike previous interventions, an act of sabotage, intended or not. The growing consensus that characteristics of the secretive hierarchical culture are at the heart of the current crisis was given expression forcefully and repeatedly at the meeting. It has taken the hierarchy of the global church nearly three and a half decades to reach that level of honesty about itself.

Benedict's theology and exegesis in his latest letter aside, his analysis of the causes of the crisis — the turbulent 1960s, the sexual revolution, the various forces of modernity, the deficiencies in seminary training — would, if made the basis for understanding the scandal, turn the church back decades.

On June 7, 1985, the back page of NCR contained an editorial addressing the problems outlined in a four-page report, the first national account ever published, of the clergy sexual abuse crisis. "Who's involved here, and what patterns of conduct emerge after events are looked at? Children, of course, are the most immediate victims," said the editorial. "Traumatized, guilt-ridden, even suicidal, they are terrified by the idea of discussing what has happened to them with parents or other authority figures.

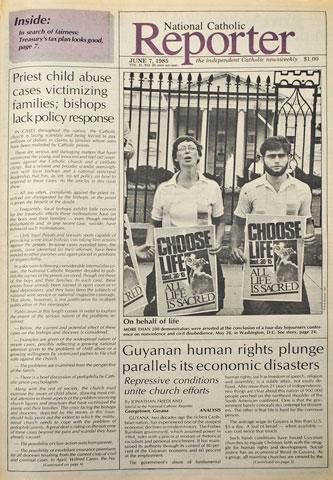

The cover of the June 7, 1985, issue of NCR

"Next, parents become victims, usually finding out what has happened to their children late in the game. Emotionally, they are tossed about by a variety of feelings: guilt for not having protected their offspring, anger at the priest who inflicted the harm and a sense of awkwardness for having to confront, in one way or another, a person they were trained to respect as a unique mediator of God's grace and love.

"Then, there are the ecclesial functionaries: the pastor, bishop and sometimes religious superior. In almost every case, these officials seem to follow an unwritten set of guidelines: Assure the parents everything will be taken care of. Caution them against getting an attorney, and by all means, plead with them not to go to the press."

The editors back then outlined quite a bit more, including the need for what they termed "ministerial boards" comprising psychiatrists, social workers, staff from facilities that deal with troubled priests, clergy, laity and "at least one attorney," and advising that parents should have access to the boards "without previous consultation with their pastor or bishop." They also wrote that repeat sexual offenders "must be separated from the rest of society."

"The church should lead social behavior, not reflect it, when it comes to seeking solutions," the editorial argued.

Thirty-four years ago a small clutch of Catholic editors and reporters who had just come into contact with the first indications of what was a budding national scandal, understood the problem in a way that would stand the test of time: The victims were children and their families; the perpetrators were mostly priests; the cover-up specialists were bishops.

Advertisement

One need not resort to theological debates or social analysis nor consult apocalyptic literature to understand what went on. In the late 1940s — long before the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and the 1960s — a U.S. priest learned of the sexual abuse of children by priests. His name was Gerald Fitzgerald, a Boston priest who founded the Servants of the Paraclete to deal with problem clerics, primarily those dealing with alcoholism. It wasn't long after he opened a center in New Mexico that bishops from around the United States began sending sex offenders.

Fitzgerald was so appalled by the assaults on children and so revolted by the perpetrators that in the 1950s he placed a down payment on an island in the Caribbean with the intent of isolating the abusive priests. That idea never became reality, but he knew they couldn't be cured. He wrote about the sexual abuse of children to multiple U.S bishops; he recommended against transferring them to new parishes or dioceses; he was asked by the Holy Office at the Vatican to explain what he knew, and he delivered a five-page response in 1962; the following year he had a personal meeting with Pope Paul VI to discuss the matter.

Paul VI knew. John Paul II knew. Benedict XVI knew. Vatican officials knew.

Enough. We've said it before and it bears saying again: It's over. Denial no longer works. Trying to blame crime and cover-up on everything and everyone except those who were actually involved is no longer persuasive.

Benedict had his opportunities as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and as pope to call the hierarchical culture to account. He took some personally courageous action, not least of which was to bring the case against the notorious pedophile and favorite of John Paul II, Marcial Maciel Degollado, head of the Legion of Christ. But he failed to hold the leadership of the church accountable.

His current meddling is neither sound analysis nor helpful to a pope making unprecedented efforts to reform the clergy culture. Benedict should follow his initial instinct and be prayerfully silent.