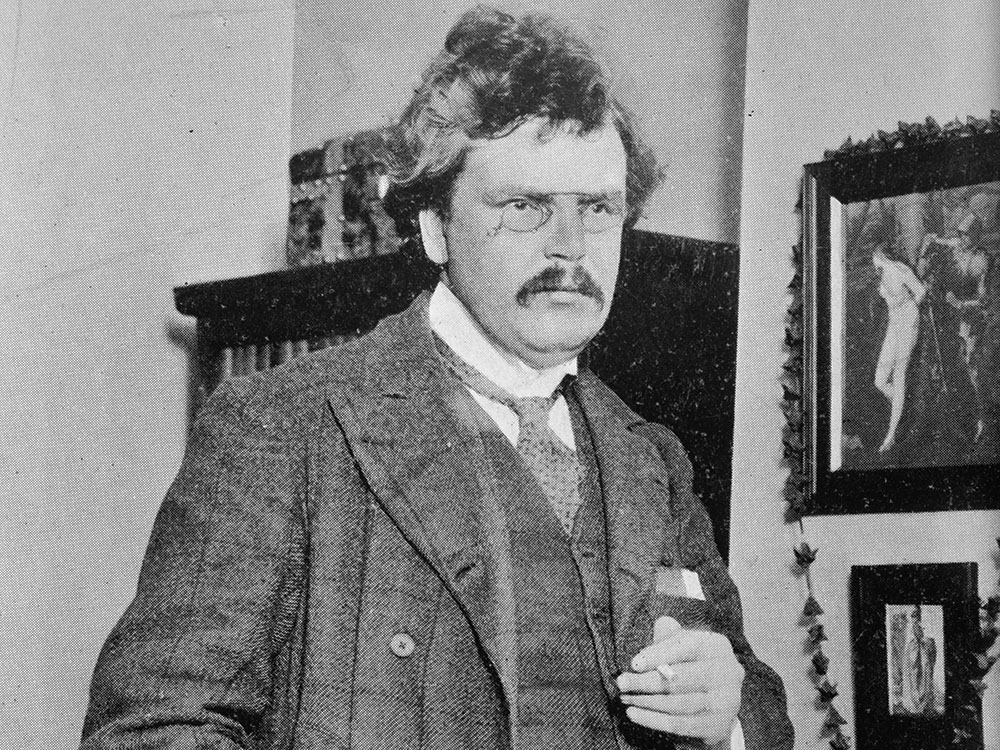

Catholic author G.K. Chesterton in an undated photo (Library of Congress/George Grantham Bain Collection)

Avid Catholic fans of G.K. Chesterton may recognize actor Kevin O'Brien from his days portraying friends and intellectual opponents of the prolific early 20th-century British writer on the Eternal Word Television Network show, "G.K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense."

For the better part of two decades, O'Brien also spoke and performed at events organized by the Minnesota-based Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton. He counted among his close friends leading Chestertonians such as Joseph Pearce, a conservative English-born U.S. writer and speaker, and Dale Ahlquist, the society's founder and president.

"I was about as in as you could be," said O'Brien, who has become estranged from his longtime friends in the society, which he left in 2021. O'Brien said he became disillusioned with Chestertonians he once admired when they accommodated themselves to right-wing political ideology.

"Trump, I think, enabled them to show themselves for who they really were," O'Brien said, referring to former President Donald Trump. O'Brien and other former Chestertonians said Trump's brand of hard-right, culture-war, nationalist politics influenced and "corrupted" large segments of the Catholic community in the United States, including the Society of G.K. Chesterton.

"I call it the great unmasking," O'Brien told NCR.

Kevin O'Brien, left, with Dale Ahlquist on the set of Ahlquist's EWTN series, "G.K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense," in 2008 (Courtesy of Kevin O'Brien)

The turmoil within the organization, which was founded as a literary society and in 2018 became an official Catholic lay apostolate dedicated to Chesterton's cause for canonization, in several ways is a microcosm of how the Catholic Church in the United States today is being buffeted by strong ideological headwinds.

Anger, frustration and disillusionment over the influence of political and ideological forces that coincided with Trump's political rise have ruptured longtime friendships and professional relationships in the society, which for years has been a staple in the conservative American Catholic universe.

Former members question the direction that Ahlquist, a former lobbyist, has taken the organization in recent years, especially his push to promote the society's Chesterton Schools Network, a rapidly-growing network of private Catholic high schools rooted in a classical European educational model that critics say appeals to ultraconservative families.

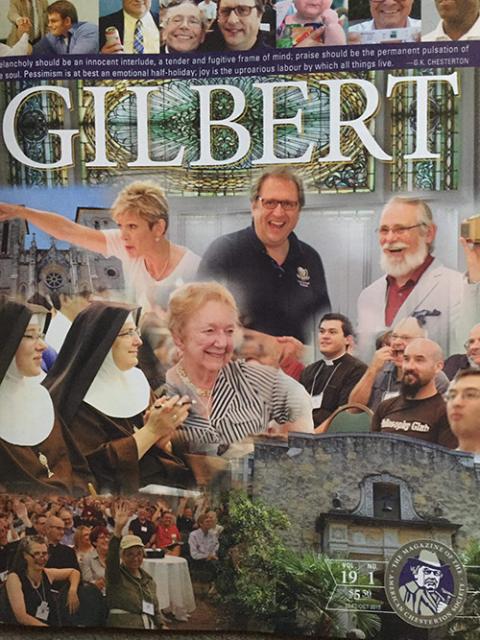

"I've never liked the schools. They don't understand Chesterton at all, especially Chesterton's attention to social justice, which they really don't care about," said Sean Dailey, who edited the society's bimonthly magazine, Gilbert, for nearly 14 years until he resigned in 2017.

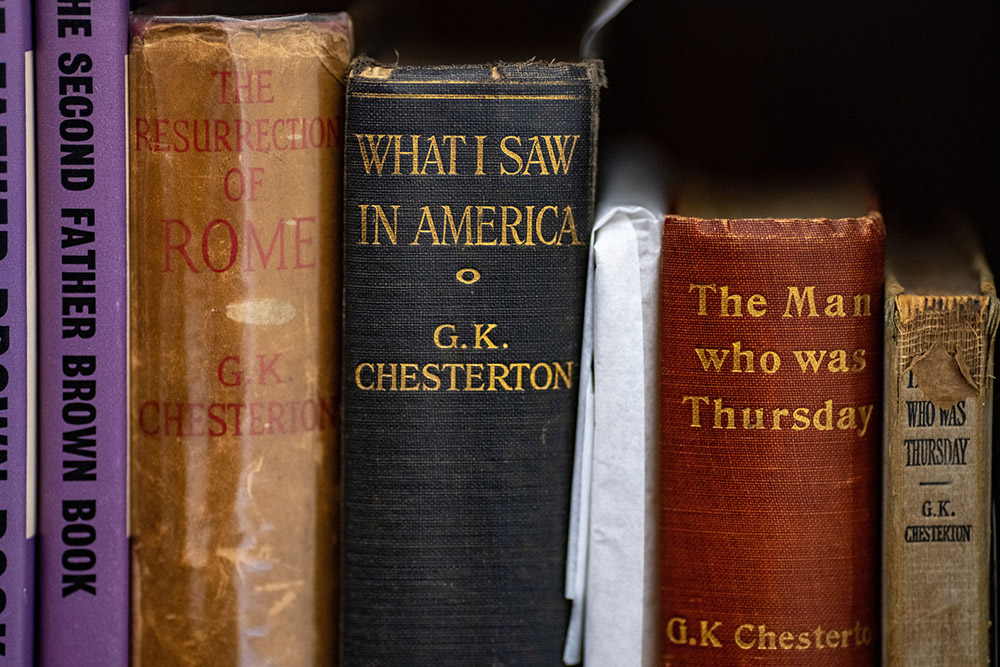

Books are seen in the Chesterton Archive housed at the University of Notre Dame's London Global Gateway in England Oct. 26, 2022. (CNS/University of Notre Dame/Matt Cashore)

The disaffection with the society has even prompted some once-ardent admirers of Chesterton to begin deconstructing parts of his legacy they had defended, including longtime concerns that Chesterton at times expressed antisemitic ideas that some former members now say make him an unsuitable candidate for sainthood.

"My days of dismissing [antisemitism], or excusing it or trying to explain it away, are over. I'll never do that again. To say it's no big deal is just not honest," Dailey said.

The Society of G.K. Chesterton is adamant that Chesterton was not antisemitic and it aggressively challenges that narrative on its website. The society also pushes back against former members' concerns that it has become politicized in the so-called Trump era.

"The Society of G.K. Chesterton is not a partisan organization. Our views do not align with either the Republican or Democrat parties," a spokesperson for the organization who asked not to be identified by name told NCR in a written response to several questions for this story. The society did not make Ahlquist and other leaders available for interviews.

'They're trying to make Chesterton into something that he really wasn't.'

—Sean Dailey

Adding that the society's conference speakers have spanned the ideological spectrum and that the society supports "open and good natured debate among people who disagree," the spokesperson suggested that the society's critics are "perhaps" angry that the organization fails "to be partisan enough to exclude those to whom they would rather not listen."

Vehicle for right-wing causes

But a half-dozen self-described Chestertonians, including those who received awards from the society, and made speeches and presented at its annual conferences, shared similar concerns about it becoming a vehicle for far-right ideological causes that they say its namesake would never have supported.

"They're trying to make Chesterton into something that he really wasn't," Dailey said.

Dailey and other former Chestertonians told NCR that the tone and tenor of the society's magazine in recent years has reflected American conservative ideology by publishing editorials sympathetic to far-right politicians like Trump and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

John Médaille, right, receives the 2015 Outline of Sanity award from Chesterton Society President Dale Ahlquist. (Courtesy of John Médaille)

They said other editorials have displayed indifference to Russia's February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, skepticism of public health measures during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, and support for abolishing public education. They noted that when George Floyd's murder by Minneapolis police in May 2020 sparked nationwide protests, Ahlquist wrote a column in which he seemed to minimize racism while plugging the society's private schools network.

"It all got more and more right-wing, and just became more and more a part of the American political debates. The more they got away from Chesterton, the less interest I had in it," said John Médaille, a retired businessman and Catholic author who in 2015 received the society's Outline of Sanity Award, an honor named after one of Chesterton's books.

"I still have the award right here on my desk," said Médaille, who teaches a social justice course for business students at the University of Dallas.

Other former members said politically conservative speakers used their platforms at the society's conferences to rail against "the secular left" and to argue for right-wing projects like abolishing public education, privatizing all health care and defending Christopher Columbus from accusations that he brutalized Indigenous people in the Americas.

Past speakers at conferences hosted by the society have included Rod Dreher, who wrote the 2017 book The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation and now frequently praises right-wing Hungarian leader Viktor Orban; Project Veritas founder James O'Keefe; and Seth Dillon, CEO of the conservative satire site The Babylon Bee.

Robert L. Kelly, who lives north of San Antonio, told NCR he attended the society's 2015 conference. Kelly, who is of Mexican descent, recalled a talk about the ancient Punic Wars that he found interesting "but also a tad xenophobic."

"More worrying was some of the conversation after that talk, which I believe was the keynote, where mostly older white men compared Mexican immigrants today to the Carthaginians in the past," Kelly said.

"When the Trump stuff started and the society was mostly silent on his ideas, clearly out of line with Chesterton's ideals and economic ideas, I muted them on Facebook," Kelly added.

'It all got more and more right-wing, and just became more and more a part of the American political debates. The more they got away from Chesterton, the less interest I had in it.'

—John Médaille

The society's spokesperson said articles in the magazine have criticized "politicians and views from both parties," and added that the society, like Chesterton, finds "much to criticize" and much to celebrate "across the political spectrum."

However, former society members such as Emma Fox Wilson, a resident of Birmingham, England, who wrote a regular column for Gilbert based on Chesterton's correspondence, told NCR that "the whole tone" of the magazine changed during the pandemic.

"They never quite unmasked themselves. They would never quite come out and say it, but they would drop a lot of hints," Wilson said, adding that she thought the society used its magazine to strike a skeptical tone on mask-wearing and vaccines.

'We couldn't criticize Trump at all'

Wilson and Dailey also told NCR that Ahlquist, in his capacity as publisher of Gilbert, refused to publish any editorials or essays that criticized Trump for fear of alienating conservative readers.

An issue of Gilbert Magazine from 2015 includes photos of former Gilbert magazine editor Sean Dailey, Emma Fox Wilson (pointing), and John Médaille receiving the Outline of Sanity award from Chesterton Society President Dale Ahlquist. (Courtesy of John Médaille)

"I was very shocked that Dale wouldn't repudiate Trump in any way," said Wilson, who wrote a column in 2016 noting that Chesterton was skeptical of millionaires and suggesting he would have been "horrified" by Trump's political rise.

"But when I tried to return to the subject [Ahlquist] told me they were hemorrhaging readers and he couldn't afford to lose more subscriptions," Wilson said.

"Dale wouldn't let us criticize Trump in the magazine," said Dailey, who told NCR that Ahlquist refused to listen to his arguments that the magazine needed to challenge Trump and his political movement in order to be faithful to Chesterton.

"Every time I suggested an editorial, Dale turned it down and did something else," said Dailey, who also said that in prior years, the magazine had published editorials criticizing Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

"There was no overall [policy] of 'Don't criticize so and so,' until Trump came along. And then we couldn't criticize Trump at all," Dailey said.

The Society for G.K. Chesterton's spokesperson told NCR that the accusations that Ahlquist — who in December 2020 was appointed by Trump to serve on the National Board of Education Sciences — refused to publish essays critical of Trump are false.

'If readers want a paper in which to prop up their favorite political candidate, or tear down their political opponents, they should look elsewhere than the editorial column of Gilbert.'

—Society for G.K. Chesterton spokesperson

Said the spokesperson, "The purpose of Gilbert magazine is to celebrate G.K. Chesterton and apply his wisdom to modern concern. It is not a partisan magazine aimed at lauding or denouncing certain politicians. If readers want a paper in which to prop up their favorite political candidate, or tear down their political opponents, they should look elsewhere than the editorial column of Gilbert. Readers who want partisan bashing can find plenty of that elsewhere."

In 2021, O'Brien told NCR, Ahlquist refused to listen to his pleas to publish an editorial in Gilbert condemning the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol building. In a May 2021 email that O'Brien wrote to Ahlquist and other society members, O'Brien expressed his concerns about what he saw as the society's deafening silence on Jan. 6 and complicity with COVID-19 misinformation.

"This is our hour to own up to what it means to be a Christian, and we are ignoring that challenge, and pretending as if it's still 1995 and we are blithely busying ourselves with apologetics and Culture Wars — when our refusal to own up to what we've done and to repent for it condemns us — quite rightly — to irrelevance both in the Church and in the culture at large," O'Brien wrote in the email, which he later posted on his personal website.

A few weeks after sending that email, to which he said he never received a response, O'Brien said Ahlquist called to berate him and tell him that the people who stormed the capitol building on Jan. 6 were not violent and that they were only acting in frustration against liberal elites.

"He told me I needed to go back to being my old self," O'Brien said.

Kevin O'Brien, left, as G.K. Chesterton's fictional detective, Father Brown, is seen with Dale Ahlquist in an undated photo. (Courtesy of Kevin O'Brien)

In response to O'Brien's accusations, the society's spokesperson told NCR that the purpose of Gilbert magazine is to promote the life and thought of Chesterton, "not to take positions on political candidates or weigh in on election fraud debates."

The spokesperson added: "We do not consider it our job to weigh in on every political matter, but rather we focus on presenting Chesterton's thought and wisdom to readers. Most of them likely welcome this as a refreshing change from the fractious and divisive atmosphere of so much other media they encounter every day. It seems significant that so much is being made of alleged private conversations here, which points to the fact that our published material doesn't provide our critics with the evidence they seek to bolster their claims of our alleged partisanship."

Accusations of antisemitism

On the question of whether Chesterton was ever antisemitic, the society has posted lengthy statements online and published entire issues of Gilbert magazine to rebut that suggestion.

"He was not racist. He detested racism and was an ardent opponent of racial theories, including antisemitism. He fought for human dignity and affirmed the brotherhood of all men. Chesterton was a friend and defender of the Jews," the society spokesperson told NCR.

Several Chesterton enthusiasts said they still find much to admire in the author but accuse the organization of airbrushing episodes in Chesterton's life that they said show he had some negative opinions about Jewish people that were historically common in Europe, especially in the years before World War II and the Holocaust.

G.K. Chesterton takes a stroll in Brighton, England, on Oct. 30, 1935. (AP)

Dawn Eden Goldstein, a Catholic author of Jewish descent, credits discovering Chesterton's writings in the 1990s with leading to her conversion to Christianity and to entering the Catholic Church in 2006. But she was unable to finish reading one of Chesterton's books, The Everlasting Man, because of what she saw as some antisemitic tropes.

"I just couldn't get any farther because of his talking about the peculiarity of the Jew, and the Jew as other," Goldstein said. "He was othering the Jew pretty badly in a way that's just not acceptable to Catholics, or for anyone really."

In 2021, Goldstein delivered a talk at the society's annual conference titled "Chesterton and My Jewish/Catholic Journey." In her nearly hourlong presentation, Goldstein drew on research from Simon Mayers*, author of the 2013 book Chesterton's Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G.K. Chesterton.

In showcasing quotes from Chesterton's writings that indicated he thought of Jews as alien outsiders who could never be loyal citizens in Christian Europe, Goldstein — who received the society's Outline of Sanity award in 2007 — argued that Chestertonians needed to acknowledge that troubling record and even do penance to show the world that the society was willing to reckon with difficult truths.

Dawn Eden Goldstein receives the 2007 Outline of Sanity award from Dale Ahlquist, president of the G.K. Chesterton Society. (Courtesy of Dawn Eden Goldstein)

"The argument I wanted to make," Goldstein said, "is to say we need to save whatever is good in Chesterton by acknowledging all the horrible stuff, and that's the only way we're going to save what's good, if we come clean and say there are many things in Chesterton we should not emulate and we need to sort those before choosing what we're going to emulate."

The society pushed back on Goldstein's talk by publishing a lengthy, nearly point-for-point rebuttal on its website, written by Brandon Vogt and Nancy Carpentier Brown. Vogt, president of the Central Florida Chesterton Society and a publishing director for Catholic outlet Word on Fire, and Brown, who has published a range of books about Chesterton, criticized Goldstein's research and brought up earlier talks on Chesterton where Goldstein had not mentioned concerns about antisemitism.

The society's spokesperson said that while "some people perpetuate the tired accusation that Chesterton despised the Jews," the society has engaged the criticism numerous times over the years and is "eager to learn specifics" from anyone who thinks it has been dishonest on the topic.

Some former society members who have deeply read Chesterton say the organization is not being intellectually honest.

Advertisement

"It's not as simple as saying Chesterton was definitely an antisemite or Chesterton was definitely not an antisemite," said Wilson.

She added that Chesterton wrote some "pretty nasty things" about Jews during particular times in his life, notably during the 1912 Marconi scandal when Jewish government officials were accused of improperly benefiting from inside information about forthcoming government contracts.

"I think he went through patches where he behaved less well, which was quite common at the time, in England and Europe. People then said things about Jews that we wouldn't today," Wilson said. "But for them to say [Chesterton] absolutely wasn't antisemitic, I don't think that's right. It doesn't solve anything, and it's not a truthful answer to the question. The truth is much more complicated than that."

Dailey said Ahlquist also did not do the society any favors when in 2008, he used a pseudonym, "Bradley Rothstein," to write a positive review in Gilbert of E. Michael Jones' book The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History.

The review, which had the headline, "Whatever You Do, Don't Mention the Jews," questioned why it was antisemitic for Jones — who has since made overtly antisemitic comments on social media — to say that the Catholic Church "has had to defend itself on more than one occasion from revolutionary movements in which the Jews played a part, small or large, and the Jews consequently faced the resentment of Christians afterwards."

The society's spokesperson said Dailey approved the use of the Rothstein pseudonym, and that it was "adopted precisely to avoid any impression that Dale or the Society endorses the full range of Jones' views, many of which are problematic. No other implication was intended, and it was not meant to be offensive or insulting in any way."

Médaille, the University of Dallas instructor, said he has long been aware of Chesterton's "skepticism toward the Jews," and added that some of his writings expressed indifference to persecuting Jews, even suggesting that they needed to wear distinctive clothes in public.

"That's a big hurdle they're going to have to get over for sainthood," Médaille said.

The writer or the would-be saint

In 2019, the then-bishop of Northampton, England, wrote to the Society of G.K. Chesterton to say he would not be promoting Chesterton's cause for canonization. In addition to saying that there was "no local cult" to Chesterton or an obvious "pattern of personal spirituality," Bishop Peter Doyle, who is now retired, wrote that the issue of antisemitism was "a real obstacle particularly at this time in the United Kingdom."

The Society of G.K. Chesterton — which in July 2018 was recognized as a private association of the Christian faithful by the St. Paul-Minneapolis Archdiocese — disagreed with Doyle's findings.

In an August 2019 prepared statement, Ahlquist contended that Chesterton had a local cult, said he was not antisemitic and suggested that Chesterton revealed his spirituality "through his writings and in his life, in his love for the Sacraments, in his abiding sense of wonder and joy, and in his tireless labor for social and political reform."

Ahlquist also said then that the society remains hopeful that another bishop, perhaps in a different diocese, will advance the cause so that Chesterton will one day be raised to the altars.

A bust of G.K. Chesterton is seen in the Chesterton Archive in London. (CNS/University of Notre Dame/Matt Cashore)

"Our Society, as a private association of the Christian faithful, remains hopeful that this will happen soon, and continues to work toward that end!" the society spokesperson told NCR.

The prospect of a future "St. G.K. Chesterton" prompts ambivalence from former society members who were uneasy about the society's evolution from a literary club founded to study Chesterton the writer into an apostolate dedicated to promoting Chesterton the would-be saint.

"The whole thing is a bit cult-y. It makes me nervous," Wilson said.

The society's spokesperson said Chesterton's writings have been life-changing and led people to convert to the Christian faith.

"This wonderful fruit has propelled our development from a literary community into a specifically Catholic apostolate, approved by the church," said the spokesperson. "Chesterton leads people to Christ, and to lead happier, holier lives in that pursuit. This is what all saints do, and we believe Chesterton does so in a very effective way, particularly in our contemporary age."

Others, meanwhile, prefer the Society of G.K. Chesterton as it was before the political tensions, the network of private schools, the designation as an apostolate and the drive to canonize Chesterton.

"I liked it better when it was a drinking club," Médaille said.

*This story has been updated to correct Mayers' last name.