As the hierarchy gathers for the Vatican summit, clergy sexual abuse survivors speak out Feb. 20-24 in Rome. Top: Alessandro Battaglia speaks at a rally with other survivors, including, at left, Peter Isely and Denise Buchanan. Bottom, from left: survivors François Devois and Olivier Savignac; Juan José Bayas; and Carol Midboe and Mary Dispenza. (CNS photos/Yara Nardi, Reuters; Paul Haring; Junno Arocho Esteves)

The so-called "summit" on the clergy sex abuse crisis was not a total failure. The process and the outcome of the Feb. 21-24 meeting of bishops at the Vatican were clearly a serious disappointment to the victim-survivors, their families and countless others who hoped for something concrete to happen. The accomplishments can only be understood in the context of the totality of the event: the speeches, especially those of the three women, the bishops' deliberations, the media reaction, and the presence and participation of the victims-survivors from at least 20 countries.

I have been directly involved in this nightmare since 1984, when the reality of sexual violation of the innocent by clerics, and the systemic lying and cover-up by the hierarchy (from the papacy on down) emerged from layers of ecclesiastical secrecy into the open. By 1985, Pope John Paul II and several high-ranking Vatican clerics possessed detailed information about what was quickly turning into the church's worst crisis since the Dark Ages.

From that time onward, bishops on various levels of church bureaucracy have been engaged in almost nonstop rhetoric about the issue that has been a mixture of denial, blame-shifting, minimization, explanations (the most bizarre, that it's the work of the devil), apologies, expressions of regret, promises of change. The rhetoric has been accompanied by procedures, policies, protocols and a few changes in canon law. The gathering in February was no exception.

There were no revelations, statements, speeches or promises from anyone involved in the meetings that were new, including the momentous statements by Holy Child of Jesus Sr. Veronica Openibo, Linda Ghisoni and Valentina Alazraki. Everything that was said has already been proclaimed publicly by someone from within the church's system, from among the victims and survivors or from their supporters.

The other element that fits right in with the bishops' pattern of response over the past 35 years is that they made promises but did nothing. People have been begging the bishops for years to stop talking about it. Stop the endless flow of empty platitudes and empty promises and do something. Unfortunately, the hierarchy's long-held belief that their words are sufficient to change reality has been completely useless.

The final press conference announced three promised concrete actions: a papal statement on how to handle sexual violation claims within Vatican City; task forces of experts to help dioceses manage abuse claims; and a handbook on how to respond to accusations. Hardly revolutionary! A plan to handle reports in Vatican City is about as relevant as a plan to handle them in Antarctica. The other two promises, however, are far from new.

In 1985, I worked with two other men who had this mess figured out at the outset. Attorney Ray Mouton, priest/psychiatrist Michael Peterson and I put together a manual called The Problem of Sexual Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy: Meeting the Problem in a Positive and Responsible Manner. It was about 120 pages long and came with professional articles on pedophilia.

Along with the manual, we also presented a plan for setting up groups of experts in various areas, to help bishops who requested assistance. This was called a "Crisis Intervention Team" and was mostly the creation of Mouton. We also urged the bishops to set up a committee to promote up-to-date research on just about every conceivable dimension of sexual violation of minors by clerics.

Advertisement

What happened? Not just rejection but a mindless insult. The leadership of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, as the U.S. bishops' conference was called at the time, rejected the manual, saying that they already knew everything that it contained. They rejected the assistance plan, claiming that they could not impose that on dioceses.

The committee idea was strongly backed by none other than Cardinal Bernard Law and Bishop Anthony Bevilacqua. However, two weeks after we discussed it with Law's representative, then Bishop Bill Levada, the plan was abruptly canceled by the conference leadership. No reasons were given and no efforts were made to replace it.

One of the more moronic responses from the bishops' conference was to equate the plan to the creation of a SWAT team to be imposed on bishops.

Finally, the insult. A spokesman from the bishops' Office of General Counsel announced at a press conference that the three of us cooked up the manual and the action plans for one reason only: to line our own pockets by selling our services to the bishops.

Postscript to the bishops' density: An archbishop, now deceased, commented to me at a reception at the Vatican embassy: "Don't worry about all this, Tom. Nobody's going to sue the Catholic Church."

This 35-year-old background information is important because it was a portent of things to come. Since that time, there has been constant tension between the victim-survivors, their families and supporters, and the papacy and hierarchy. The dashed expectations for action, any action by the hierarchy, is not surprising but in keeping with the bishops' defensive legacy. Anything they do has to be done on their terms and on their timetable, or it is ignored.

But that tactic has been a disaster for two reasons: First, the bishops never expected that the victim-survivors would find their voice, organize and take control of the ongoing history of sexual violation and, second, the secular legal systems in one country after another are treating the church leaders the way they would treat anyone involved in a criminal enterprise. The deference that protected the bishops for centuries is rapidly withering to nothing.

Those who are struggling to find a positive spin for the meeting, looking for reasons to put the institutional leadership in good light for its own sake, don't seem to see that this is not about rescuing the pope and bishops. It's about justice for the survivors.

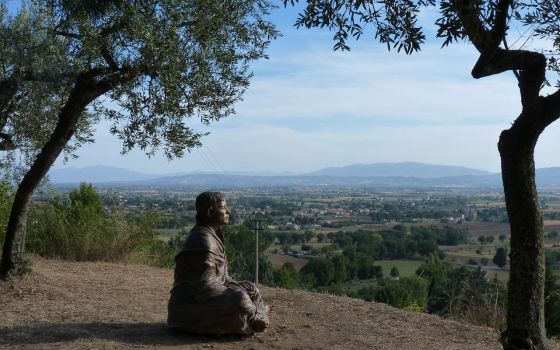

Pope Francis leads the opening session of the meeting on the protection of minors in the church at the Vatican Feb. 21. (CNS/Vatican Media)

After 35 years of pious platitudes, empty promises, baseless excuses, demonizing victims and fighting the march to justice at every turn, Pope Francis and the bishops should realize that an extension of the legacy of past defensive behavior would fall flat on its face, and it did. The reality, whether the pope likes it or not, is that the institutional church cannot fix itself. Its past attempts at doing so have failed. Future attempts such as the scheme to have metropolitan archbishops manage the prosecution of bishops accused of abuse or complicity will only end up the same way every other attempt run by the church ended up: a failure.

Now to the positives. The fact that the pope convened the leadership of every bishops' conference in the world is a major feat in itself. No matter how you cut it, this should be a sign that the pope takes the issue seriously and, hopefully, for most of the right reasons.

He said the purpose was to raise the bishops' consciousness and educate them on the serious, toxic nature of sexual abuse (something they should have known before they even went to the seminary). That is a very, very tall order in light of the decades of behavior by bishops all over the world. Still, the conference gave voice to some people who minced no words and gave it to them straight without softening the message with any phony excuses or praise for how wonderful it is to have the bishops and pope all together.

Yet the same thing happened at the historic meeting of the U.S. bishops in Dallas in 2002. Given the bishops' collective history in the U.S. since, it's obvious the inclusion of straight-talking victims and survivors back then was for show and not enlightenment. We can only hope and pray that this time it will be different.

The Vatican summit produced no decisive, action-oriented results, just more platitudes and promises. I consider this a positive because it should remove any doubt about whether the Vatican and the hierarchy have the ability or the will to take the radical steps essential to fixing the problem. It is also positive because it showed what has been obvious for so long: The church has responded and will continue to respond to sexual violation and to its victims in a pastoral and decisive manner, but it is the lay men and women of the people of God, and not the clergy, who have been and will continue to be the driving force in this.

The reality, whether the pope likes it or not, is that the institutional church cannot fix itself.

The most stunning result of the four days in Rome was nothing the pope or bishops said or did, but what their meetings inspired, and that was the unprecedented gathering of victims, survivors and their supporters from all corners of the globe. They were organized, articulate and determined. While the participants of the meetings droned on in the Vatican, the centuries-old scourge of sexual violation and rape by clerics of all ranks, the sole reason for their presence, was clearly proclaimed for the church and for the world by those who had experienced it.

The stark contrast between what was happening on the official, church-run level and what was happening in the streets further enhanced the credibility, sympathy and support for the survivors and their supporters, and not only those in Rome but the countless others throughout the world whom they represented.

The clergy abuse phenomenon is the worst crisis the church has experienced in more than a thousand years. The Protestant Reformation and its follow-on, the Council of Trent, were about doctrine, church structures and inept clergy. This is about something far worse, the pandemic of sexual violation and rape of countless vulnerable people, especially children, and the systemic enabling of the same by the popes and the hierarchy.

When will it be over and what is needed to fix it? The answers are obvious, but they invoke such fear in the clerical elite that they aren't even able to discuss them. This nightmare will continue as long as the hierarchical system that created and sustained it exists in its present state. The reasons for this phenomenon are deeply rooted in the church's institutional structures and the theological excuses that support them.

It will take a radical, fundamental process of change before the entire church truly reflects what it is supposed to be, the people of God.

[Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer and inactive priest, has long served as an expert for lawyers representing victims of clergy sex abuse.]