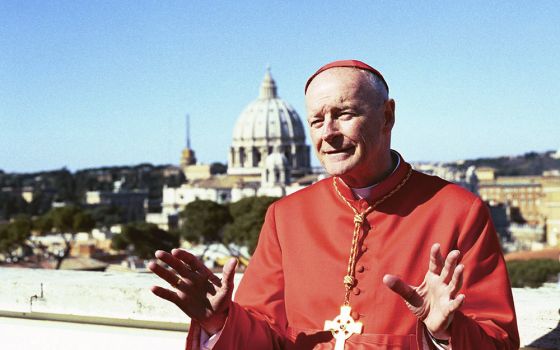

New Cardinal Theodore McCarrick addresses the media on the roof of the North American College in Rome following a consistory ceremony at the Vatican Feb. 21, 2001. McCarrick was among 44 new cardinals created by Pope John Paul II. (CNS/Carol Zimmermann)

When Pope John Paul II made Theodore McCarrick a cardinal in 2001, the archbishop of Washington, D.C., was a silk-between-the-fingers fundraiser. A year later, when the pope summoned the U.S. cardinals to Rome to confront the abuse crisis, McCarrick took the lead at press conferences — a bold move, given his revelation to The Washington Post and CNN that accusations against him had been investigated and found false.

In the ensuing years, McCarrick traveled the globe as an unofficial church diplomat, and rumors spread that he had slept with seminarians while a bishop in Metuchen and Newark, New Jersey, using a beach house on the Jersey Shore. Rumors no journalist could pin down.

As the genial, glad-handing cardinal gained a high media profile, he seemed to be almost everywhere, even leading graveside prayers on TV at the funeral for Sen. Edward Kennedy.

Theodore McCarrick prepares to celebrate Mass at his titular church of St. Nereus and Achilleus in Rome April 14, 2005. The then-cardinal was in Rome to participate in the conclave that elected Pope Benedict XVI. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

And yet, as we now know from the 449-page Vatican report on McCarrick, two New Jersey dioceses had quietly paid settlements to victims by 2007. In 2018, after more lawsuits and survivors spoke out, a Vatican tribunal at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith found him guilty of moral crimes. Pope Francis approved McCarrick's laicization, stripping him of priestly status, and ordered an investigation on how McCarrick had avoided detection for so long.

The task of compiling that report fell principally to Jeffrey Lena. Lena is a lawyer based in Berkeley, California, who has defended several cases against the Holy See in U.S. courts on jurisdictional grounds.

Lena earned a master's in American history at University of California, Berkeley, then switched to law school, studying at Berkeley and the University of Milan. He began dividing his time between a law practice in Berkeley and teaching law part-time in Europe. In 2000, he began representing the Holy See as a defense attorney in a range of actions.

In 2013, Lena prevailed when a federal court dismissed an Oregon case filed by plaintiff attorney Jeff Anderson on behalf of an abuse survivor, alleging direct Vatican knowledge of the perpetrator's history. As the church crisis spread globally, Lena spent longer and longer stretches in Rome.

Lena was a background source for me on reporting trips to Rome; several years had passed since I last saw him, when he called me in early September. He was in Berkeley, barred by the pandemic from flying back to Rome. He told me he was writing the McCarrick report.

I was on vacation in Santa Fe, New Mexico, hiding from the apocalypse — flooding in New Orleans, fires out West, COVID-19 everywhere. Lena brooded about the burning skies, then turned to the task.

He wanted information about the impact on news media in 1994 when a man dying of AIDS withdrew his abuse lawsuit against Chicago Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, saying he could not trust his memory. In Vows of Silence, Gerald Renner and I wrote about the overnight shift in news coverage from investigations of bishops concealing predators to a new focus: "false memory," quack therapists, vagaries of the mind.

It took nearly eight years, and The Boston Globe's 2002 Spotlight series, before newsrooms refocused on the church crisis, which had never really gone away. The Globe ignited a chain reaction of coverage that led to the bishops adopting a youth protection charter at their June 2002 meeting in Dallas.

Circling like a lawyer in a deposition, Lena kept asking me about the aftermath of the Bernardin events. Intrigued to be a source for a Vatican report, I obliged, providing source citations and comments via phone and emails, my curiosity mounting about his report.

I heard nothing more until Nov. 12. The Vatican Secretariat of State posted the "Report on the Holy See's Institutional Knowledge and Decision-Making Related to Former Cardinal Theodore Edgar McCarrick," listing no author. I achieved a cameo role in the long footnote on Page 215 on the 1994 events aforecited.

Advertisement

The report is "historic and unprecedented," Lena's adversary, Jeff Anderson, told me. Anderson, in a statement on his firm's website, credited Lena for the investigation.

I called Lena for comment; he said no, referring me to the "factual record." In other words, do your own analysis.

For years, I have argued in articles and interviews that the Vatican needs an independent judiciary to prosecute negligent and predatory bishops. Francis has sacked a string of bishops, met with survivors, pushed canon law reforms.

The McCarrick report trains a forensic lens on the religious monarchy's secrecy-addled system of promotions and justice. For journalists, the document is a goldmine.

During the mid-1990s as media coverage retreated, the report explains, three New Jersey bishops failed to investigate accusations from seminarians subjected to queasy beach house sleepovers with "Uncle Ted." Lena quotes David Gibson, then at the Newark Star-Ledger, on the futility of trying to track leads on McCarrick's behavior.

The document made me see how often McCarrick had voiced his sympathy for Bernardin as wrongly accused, a virtual martyr. Clearly, this was McCarrick fortifying a firewall for allegations against himself. Now 90, a layman in seclusion, McCarrick has never admitted to any sexual activity — a cast-iron case of denial.

The report avoids questions. Why did so many bishops in the late '90s keep concealing clergy sex offenders? Were they emboldened to continue business as usual after seeing the media's sympathetic portrayal of Bernardin? Deeper still, what message was Pope John Paul II sending bishops in those years?

Left: Theodore McCarrick, then cardinal archbishop of Washington, D.C., and Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, then papal nuncio to the U.S., at the White House in March 2001 (CNS/Reuters). Right: New York Cardinal John O'Connor in 1999 (CNS/Nancy Wiechec).

The report quotes a remarkable 1999 letter from New York Cardinal John O'Connor to Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, the papal nuncio or Vatican ambassador in Washington, citing "grave fears and those of authoritative witnesses" at the possibility of "scandal and widespread adverse publicity," should McCarrick go from Newark to Washington.

This opens a rare viewfinder on the inner workings of the ecclesiastical power structure. Montalvo tells McCarrick of his precarious position. McCarrick sends a long letter to Bishop Stanislaw Dziwisz (pronounced Gee-vish), John Paul II's trusted Polish secretary, declaring that he had never had sexual relations with anyone. The timing of these events is striking.

In 1999, Dziwisz and Secretary of State Cardinal Angelo Sodano had bolstered John Paul's support for another pedophile, Legion of Christ founder Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado. In a 1998 canon law case filed in Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith tribunal, eight ex-Legionaries (one a priest in Spain) wanted to testify how Maciel sexually abused them as teenage seminarians.

Polish Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz presents a framed portrait of Pope John Paul II to members of St. Patrick Parish in Miami Beach Feb. 3, 2005. (CNS/Tom Tracy)

The man who spearheaded that procedure, Mexico City college professor José Barba, went to Rome, had a letter on their grievances translated into Polish and delivered to Dziwisz, entreating him to share it with the pope. Eight sexual assault survivors wanted to testify.

Sodano pressured Ratzinger to halt action against Maciel. The Legion gave Sodano financial gifts, at least $5,000 at a time, as several ex-Legionaries told me for a 2010 NCR series. One priest said he had given Dziwisz $50,000 to welcome a Mexican benefactor of the Legion and his family at a private Mass by John Paul in the Apostolic Palace. He called it "an elegant way of giving a bribe."

The Vatican report suggests that John Paul recalled his decades in Poland when the communist secret police tried to smear priests with false accusations, thus embracing McCarrick's innocence.

John Paul biographer George Weigel is now arguing that the pope was a victim of McCarrick, a pathological liar. A convenient jump cut from Weigel's second book on John Paul, The End and the Beginning, in which he chalked up the pope's failure on Maciel to "mysterium iniquitatis," the mystery of evil. But John Paul's refusal to let the Maciel victims testify, while he continued to praise Maciel in public events, smacks of criminal negligence.

The larger question evaded by Weigel is why John Paul during the 1990s, while receiving a series of reports from bishops in many countries, took no action; he sank in a cocoon of passivity as clergy abuse scandals made explosive news in North America, Ireland and Australia. Time and again, he received information on cases from bishops across the English-speaking world; the early wave of legal actions stemmed from legal systems that allowed probing discovery subpoenas that caused bishops to release secret files.

In 1993, O'Connor spoke bluntly in a speech in Rome at the North American College: "It's getting increasingly difficult for some priests and some bishops to hold their heads up. Everyone is under suspicion," Cindy Wooden of Catholic News Service reported on March 11, 1993. "Real damage is being done in many cases — real horrifying damage." In 1999, he blew the whistle on McCarrick.

During McCarrick's years in Washington, he donated $600,000 to clerics at the Vatican and elsewhere — including $90,000 from 2001 to 2005 to John Paul II — that came from his private archbishop's fund. The Maciel case sat in limbo until December 2004, five months before John Paul died, when Ratzinger ordered the survivors' testimony. What kind of justice system is this?

In 2006, Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI, banned Maciel from ministry. In 2008, Maciel died. Citing no sources, the Legion stated he went to heaven. A year later, the Legion revealed its utter shock upon learning Maciel had sired children out of wedlock.

Benedict's decision to put John Paul on a fast track for sainthood begs another question. Was he concerned that scandal-skeletons would hit the media (as we see today) should the process be prolonged? Why the rush?

Francis canonized John Paul in 2014.

What about the men surrounding John Paul in the Apostolic Palace when he gave McCarrick the green light?

In 2018, Pope Francis greets Cardinal Angelo Sodano, then dean of the College of Cardinals, during the pope's annual pre-Christmas meeting with officials of the Roman Curia and College of Cardinals. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Sodano grew more damaged by media coverage for his role in defending such pedophiles as Chile's notorious Fernando Karadima, whom Francis defrocked, and Vienna Cardinal Hans Hermann Groër, who resigned when former Benedictine seminarians raised accusations in 1995. Sodano blocked any Vatican move against him. Last December, when Francis "accepted the resignation" of Sodano as dean of the College of Cardinals, he was bad baggage.

The past is stalking Dziwisz, who became a cardinal under Benedict and returned to Krakow, Poland. His record of sheltering Polish predators triggered a stunning investigative report by Marcin Gutowski of TVN24 in Warsaw.

"The McCarrick report tells much about Dziwisz's support of the now defrocked cardinal," Stanislaw Obirek, a professor* at the American Studies Center, University of Warsaw, told me by email.

The ruling Law and Justice Party is a nationalist movement with strong support from the Polish Catholic hierarchy. Its main architect is Dziwisz, who, as the bishop of Krakow in 2010, showed an authoritarian side sympathetic to this government that's been undercutting democracy. Since its 2015 political takeover, Dziwisz has been silent on the government's cynicism toward Pope Francis' advocacy for refugees and immigrants. The myth of the impeccable Pope John Paul and his good-natured Polish secretary has collapsed. Ironically, we owe this merciless view of both men to Pope Francis for ordering this report.

The McCarrick report spotlights a third man in the Apostolic Palace when McCarrick made his 1999 plea that would secure his cardinal's red hat in Washington. This was Bishop James Harvey, who had become head of the papal household. A native of Milwaukee, Harvey studied in Rome and had a series of postings in the Holy See's diplomatic corps before becoming a bishop.

In 2003, John Paul elevated him to an archbishop. This happened a month after a 2003 Dallas Morning News report that Harvey had helped a Cincinnati cleric, Msgr. Daniel Pater, become a diplomat for the Holy See, despite accusations that surfaced in the 1990s of his abuse of a 14-year-old girl. "The Vatican knew the status of the case," a spokeswoman for the Cincinnati Archdiocese told Dallas Morning News reporter Reese Dunklin.

U.S. Cardinal James Harvey, archpriest of the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, arrives to preside over the ordination of eight deacons from Rome's Pontifical North American College, in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Oct. 1. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Msgr. Lawrence Breslin of Cincinnati told Dunklin that he had alerted Harvey to Pater's record. Breslin said that Harvey told him the Secretariat of State (under Sodano) knew the priest "had some problems in the States, and it'd pass over."

As quoted by the newspaper, Breslin said, "I told this man, 'It's not going to pass over.' "

Breslin warned Harvey again, in 1999. The bishop told him that Pater's abuse record meant he would not be eligible for a post as nuncio, or Vatican ambassador. When the journalist called him for comment, Harvey said he did not remember the talks with Breslin.

When the 2003 report appeared in the Dallas Morning News, the Vatican yanked Pater from his post in India and sent him back to America.

Benedict made Harvey a cardinal; he is now archpriest, or pastor, of one of Rome's illustrious basilicas, St. Paul Outside the Walls.

The deeper story behind the McCarrick report is Francis' rationale in releasing a devastating portrait of the inner workings of the hierarchy, laid out in dry prose without opinions. The language of cardinals and bishops constantly referring to one another as His Excellency and Your Excellency speaks volumes about the cozy back-patting of an elite world, shielded from the norms of justice. Perhaps, after years of personally hearing survivors' wrenching stories and acting as a prosecutor of certain bishops, removing or defrocking them before the McCarrick spectacle, Francis felt himself, nay the church, swamped by systemic pathologies. If nothing else, the document is a shot across the bow to prelates trying to guard guilty back pages.

Anderson, who lost the Oregon case against the Holy See to his legal adversary, has successfully sued scores of dioceses. Anderson was stunned by the report. "The Vatican engaged a third-party, non-clergy lawyer to conduct the investigation," he told me. "We gave him witnesses to interview. Lena amassed an extraordinary body of evidence, some of which we have never seen, in exposing a clerical system that put children in peril for decades. These findings will help survivors seek justice."

Three days after I spoke to him, Anderson announced the filing of a lawsuit in New Jersey against the Holy See, on behalf of four McCarrick victims, calling on the Vatican to release secret files of perpetrators.

[Jason Berry, the author of three books on the Catholic Church, is finishing a documentary based on his recent book, City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300.]

*This article has been edited to correct Obirek's position at the American Studies Center.