Priests sit below the statue of St. Peter as Pope Francis celebrates Mass marking the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican June 29, 2018. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Editor's note: Jason Berry was the first to report on clergy sex abuse in any substantial way, beginning with a landmark 1985 report about the Louisiana case involving a priest named Gilbert Gauthe. In 1992, he published Lead Us Not into Temptation: Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children, a nationwide investigation after seven years of reporting in various outlets. In the foreword, Fr. Andrew Greeley referred to "what may be the greatest scandal in the history of religion in America and perhaps the greatest problem Catholicism has faced since the Reformation."

Berry followed the crisis in articles, documentaries, and two other books, Vows of Silence: The Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II (2004) and Render unto Rome: The Secret Life of Money in the Catholic Church (2011), which won the Investigative Reporters and Editors Best Book Award. Given the current moment and its possibilities and the fact that Berry is singular in his experience covering the scandal from multiple angles, NCR asked if he would write a reflection on the matter as the church's bishops are about to gather in Rome to consider the issue. Below is the second of three parts. Read Part 1 here.

Everything in this spreading crisis revolves around structural mendacity, institutionalized lying. For years, bishops proclaimed the sanctity of life in the womb while playing musical chairs with child molesters. High-dollar lawyers facilitated church officials' stiff-arm response to survivors scarred by traumatic childhood memories.

The media narrative of survivors seeking justice has cut a jagged trail through the mind of the church. The concealment strategies, unearthed in depositions and church documents, show how bishops and religious order superiors, sometimes paying "hush money" settlements to avoid scandal, controlled the fate of the priest and kept the closed system operating. "Convinced that they know the truth — whether in religion or in politics — enthusiasts may regard lies for the sake of this truth as justifiable," writes Sissela Bok in Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life. "They see nothing wrong with telling untruths for what they regard as a much 'higher' truth."

Clashing with that rationale are insiders who couldn't swallow the lies and leaked information. The man who did more to shape my reporting of the Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana, in 1985 was such a specimen; though even now I am not entirely sure what fueled him.

In June 1984, attorneys for six families with nine boys — victims of Fr. Gilbert Gauthe, a pastor in rural Cajun country — negotiated a $4.2 million settlement with the diocese. Gauthe meanwhile was indicted on 33 criminal counts, including aggravated rape of a minor, which carried a life sentence. In early 1985, as I read civil depositions of Bishop Gerard Frey and other diocesan officials, Gauthe sat in a mental hospital. Ray Mouton, his attorney, negotiated with the tough-minded prosecutor, Nathan Stansbury, seeking a plea bargain.

The depositions yielded information of another pedophile, Lane Fontenot, whom the bishop had sent to the same Massachusetts church treatment facility, House of Affirmation, before Gauthe.

Fontenot had not returned to Louisiana. (House of Affirmation closed in 1990 after its director, Fr. Thomas Kane, skimmed funds to buy resort properties in Florida and Maine. Kane moved to Mexico; he was later sued for abusing a youth; the case settled for $42,500.)

Fr. Gilbert Gauthe (CNS)

I had a joint assignment for NCR, which published a long piece on June 7, 1985, and Lafayette's weekly Times of Acadiana, which ran my reports from May into early 1986, as I discovered other clergy predators in the diocese. The major leads came from a civil case involving Gauthe. Lafayette attorney J. Minos Simon (pronounced Sea-mon) was a brilliant, tenacious maverick, representing a boy and his parents against the church. Simon filed a discovery request for files on 27 priests to determine if they were homosexuals or pedophiles. The diocese, he argued, had a "risk" strategy of tolerating sexual activity by priests behind the cover-up. Simon saw scant distinction between homosexuality, an orientation, and pedophilia, a pathology. In getting to know him, I argued with him, saying that one did not equate with the other; he had little interest in the distinction. He wanted a big win.

Defense lawyers derided Simon's list of 27 priests as a "fishing expedition." In the legal tug of war, I realized that Simon had an insider feeding him sensitive material. I began asking for access to the source, pledging to protect anonymity. Finally, the lawyer said, "I think he's ready."

The Times of Acadiana editor, Linda Matys, and I did not want to out priests in relationships with men. Our focus was crimes against children, not ills of celibacy.

The source called me: his voice had a soft, lyrical cadence of the Cajun patois, too dulcet for the enormity of what he had to say. As he spoke of different priests on the list he seemed to know most of them personally. Of one, he said, dripping sarcasm, "From his seminary days, he boasted of his conquest of virile males."

"Were these adults or youngsters?" I asked.

"Oh, they were all ages."

He bristled with contempt for the impact of a gay clerical culture. Who is this guy, I wondered. Had he ever been a priest, I asked.

"No."

Besides Gauthe and Fontenot, I asked about other men on the list who had been removed. "How about recycled?" he said.

"It's a better word. Everyone on the list."

Telling him that I could not write anything about what he shared until we met, and he gave his name, I promised not to reveal his identity. He seemed comfortable with that, and that night on the phone he kept talking. As I went down the list, more questions, more answers, the cynical chuckles suggested a well of knowledge about a culture most Catholics had no idea existed. How did he know all this? "It's like a club, my good man. And those in the club share the information with other people."

Besides Gauthe and Fontenot, I asked about other men on the list who had been removed. "How about recycled?" he said. "It's a better word. Everyone on the list."

All 27 men recycled for molesting youths? "For sexual misconduct," he averred. "I can't say with children." He went down the list, rattling off drunken sexual outbursts, arrests at public places that cops left the diocese to handle, transfers to new parishes after lovers' quarrels and then some. If I only used a fraction of the material, the picture of clerical life was awful.

I saw where Simon got his theory of homosexuality as a risk factor in the cover-up. I asked the source why he called the lawyer. "When I saw him on TV, and what they were doing to him it offended me." I asked if he was afraid of getting caught. "I'm not in this by myself. I have people in every office and they will go to their graves before they sneeze."

We agreed to talk again. Using a directory of diocesan priests to look up numbers, I spent endless hours on the phone, calling dozens of priests, trying to get information on those listed. Quite a number wouldn't talk, but a good many did, predicated on anonymity. Several men brooded about the breakdown of discipline at the local Immaculata Seminary, which had since closed. I got confirmation of two other pedophiles.

The source invited me to his home, showed his driver's license, and explained that his job as a choir director brought him in contact with many priests. He said he'd been abused as a child by a custodial figure, suggesting he had reason to offer Simon help in his case. He told me that Lane Fontenot, since his stay at House of Affirmation, was in residence at Gonzaga University, in Spokane.*

I called the priests' residence at Gonzaga, a Jesuit university, where Fontenot had earned an M.A. in spirituality. The priest who answered said he knew nothing of abuse allegations — Fontenot was "in residence between assignments." He put me on hold to see if Fontenot would talk, but found him "unavailable." Several months later Fontenot was arrested for abusing a youth as a counselor in a rehab center and spent time in jail. In due course I identified three other priests sent away.

In 1985 Gauthe agreed to a 20-year plea bargain. (He would eventually be released after 10 for good behavior.) Simon took his civil case to trial several months later and won a $1.25 million jury verdict.

The Times of Acadiana series culminated in early 1986 with a long report on how the diocese had recycled seven child predators over many years. We could not identify two of them at the time for lack of legal documentation; but people in the chancery itself were giving me leads, confirming why the men were removed. Of those two, David Primeaux left the state, married and established an academic career in Virginia, but committed suicide in 2012 after past victims reentered his life. (I was long back in New Orleans by then.)

The other unnamed cleric was Valerie Pullman, who died in 2017. He went to a church treatment facility in the late 1980s, and the diocese subsequently paid a settlement to a victim, according to the industrious reporting of Lafayette's KATC-TV in its recent documentary series, "The List." Lead reporter Jim Hummel cited 42 sex-abuser clerics removed over many years. The diocese years earlier had acknowledged fifteen, but Bishop J. Douglas Deshotel had not, as of this writing, released a list.

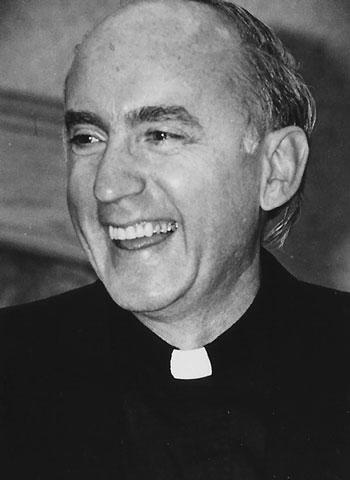

Bishop Gerard Frey in 1986 (NCR photo/TimMcCarthy)

When my final piece on the cover-up ran in 1986, so did a Times of Acadiana editorial. By then, Linda Matys was editing a San Antonio weekly. The new editor, Richard Baudouin, called on Bishop Gerard Frey and the vicar-general Msgr. H.A. Larroque to resign, and if they didn't, for the Vatican to remove them. In response, an influential monsignor, Al Sigur, and a retired judge, Edmund Reggie, fomented an advertisers' boycott that cost the paper, then billing at about $1 million annually, some $20,000 before cooler heads prevailed.

But the Vatican did respond. That summer, Rome sent a coadjutor bishop, one designated to succeed the prelate when he retires. This was Harry Flynn of Albany who quickly ingratiated himself with the Cajun flock, while Bishop Frey, battered by the crisis, soon retired. Frey at least met with some of the victims and felt their wrath.

The cover-up story line can expire from waning media interest, particularly with the slow pace of in civil litigation, natural causes, or spring to life anew, like mushrooms in a fertile field, depending on the internal dynamics. The Lafayette Diocese is a case study of deception seeding deception.

Larroque as vicar general was gatekeeper of the secrets. Instead of being fired, he became Flynn's right hand. In 2014 Minnesota Public Radio investigated Flynn because of his subsequent role in concealing abusive clerics as the Twin Cities' archbishop. He had gotten there based on his reformer's image in Lafayette. The MPR team got access to documents in a federal case between the diocese and its insurers over disputed payment percentages in abuse settlements. MPR reporter Madeleine Baran found "no suggestion that Flynn called police about priests accused of sexually assaulting children. Hundreds of documents reveal that Flynn's diocese used many of the same aggressive legal tactics that he would later employ in the Twin Cities. Attorneys hired by the diocese argued that victims waited too long to come forward and that the public didn't need to know the names of accused priests. The diocese fought efforts by victims to seek compensation from the church and focused on keeping the scandal as private as possible, which meant that fewer victims came forward to sue."

Bishop Harry Flynn in an undated photo (CNS)

The MPR series spurred Lafayette's KATC-TV to start its investigation.

One predator recently identified by KATC was my source. Maura Dwight Hebert worked as a choir director in a town outside Lafayette. In 1988 a Lafayette police officer phoned, telling me he'd been arrested in California on a fugitive warrant, after an indictment for abusing a boy and a girl, which I hadn't known about. "We know he was your source," the cop said.

Stunned, I admitted nothing about how I knew him. Later I wondered if Dwight had blurted something, hoping it might somehow give him leverage in dealing with the law. He was in jail when I accepted his call, and assumed we were being taped. It was a sad, brief exchange, his voice haggard, asking me to pray for him. After pleading guilty to one count of carnal knowledge, he drew a 10-year sentence, but was released after serving one. He died in 1990.

Why did he go to Simon, now deceased, and leak so much to me? I can only speculate, but with hindsight I suspect revenge was a motive, that he'd been bitten in that clerical vipers' nest he described, and wanted payback. Twenty-nine years after his death, I can only speculate.

The lesson I draw from Lafayette is that bishops' obsession with protecting priests will bend against common sense, time and again. In October Bishop J. Douglas Deshotel announced that Msgr. Robie Robichaux, was put on administrative leave. He had been accused in 1994 of having sex with a teenage girl between 1979 and 1981. Deshotel did not answer questions on "what action any of his predecessors took, if any, when the allegation was first made two dozen years ago," reported The Acadiana Advocate. A second woman soon made accusations on KATC. Robichaux was on the diocese's canon law tribunal handling marriage annulment cases.

In late November, police raided the offices of the U.S. bishops' conference president Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Houston-Galveston. They wanted files on Fr. Manuel La Rosa-Lopez, a pastor who was arrested on four counts of indecent behavior with youth. "Despite a 1992 accusation of inappropriately touching a sixth-grade boy, the diocese allowed La Rosa-Lopez to be ordained and to move from church to church — where, allegedly, he abused another boy and a girl," writes Lisa Gray of the Houston Chronicle.

Police also sought information on Fr. Alberto Maullon, a judge on the diocese's canon law tribunal, "who pleaded guilty to indecent exposure charges related to an adult bookstore sting in 2010," as reported by Nicole Hensley, also of the Chronicle.

Books about canon law are pictured in the library at Catholic News Service in Washington. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Maullon did not serve jail time for exposing himself to an undercover cop, a crime in no way equal to felony child abuse. "That's not a canonical crime, nor is sexual misconduct with an adult under the 1983 code," Cafardi, the canonist and former Duquesne law dean, told NCR. "It was a crime under the 1917 code. In 1967 bishops gave canonical scholars principles for reform; one was to reduce the number of canonical crimes."

According to canon lawyer Thomas Doyle, an inactive Dominican priest who became an expert witness against the church in abuse cases: "Canon 1395 could apply though I've never seen it done: 'If a cleric has otherwise committed an offense against the sixth commandment with force or threats or publicly or with a minor.' 'Publicly' is not an adjective attached to child abuse or rape. Exposing himself in a porn store is public. … Even if they don't consider it a canonical crime that doesn't mean it's OK."

Until recently, Maullon was identified on the archdiocesan tribunal website as Defender of the Bond, a canon law position charged with upholding the validity of marriage in cases for annulment. To secure an annulment, a divorced man and woman answer highly personal questionnaires. The tribunal weighs their request to start against the canonist defending the marriage vow — in this case a priest caught in a sting at a pornographic book store. Do the painful admissions by ex-spouses meet his test?

According to canon law scholar Nicholas Cafardi: "The canonical process is not supposed to be adversarial. Both sides search for truth. The Defender of the Bond is there to show the lack of strength of arguments against the invalidity but is not supposed to go overboard. Can a flawed individual do an honest job? It doesn't mean that person lacks the ability as Defender of the Bond. On the other hand, one could say that a person holding office in the church should have complete and utter integrity. It's a character flaw that impacts on the perception of his ability to do his job."

The priest shortage is one reason behind strange personnel decisions; but the stranger folds of denial, and tolerance stem from clericalism — the culture of power and privilege that inures some clerics in a world without accountability.

In this Feb. 9, 2012, file photo, retired Bishop Joseph Imesch of Joliet, Illinois, meets Pope Benedict XVI during a U.S. bishops' ad limina visit to the Vatican. The Illinois bishop died Dec. 22, 2015 at age 84. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

A striking example of that culture rises from the 1985 testimony of Bishop Joseph Imesch. The lawsuit was by a victim of Fr. Gary Berthiaume, who had done six months in jail in Michigan in 1978 after molesting the victim as a teenage boy. The plaintiff had a brother, also abused. Imesch, a Detroit auxiliary bishop when the crimes occurred, visited Berthiaume in jail. Attorney Mark Bello asked if homosexuality violated the promise of celibacy. Imesch replied: "Sure."

Bello: "What do you feel, or do you know, is the penalty for violation of these promises?"

Imesch: "Eternal hellfire. I — you know, what's the penalty? Put in that I laughed."

"At the question or the answer?"

"There is no penalty. The penalty — that's the moral failing or fault with the person."

Berthiaume took the Fifth Amendment repeatedly in his deposition, which I obtained in 1986. The lawsuit settled for $325,000. Imesch helped him get a parish in Cleveland. Unbeknownst to Michigan police, and Imesch, Berthiaume had molested four brothers in another Michigan family. They eventually received a $60,000 settlement. Cleveland parishioners had no clue.

With an assignment for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, I knocked on the rectory door in fall of 1986. Berthiaume refused to speak on the record (though denounced me for "lack of scruples.") The Cleveland diocese refused comment — and then threatened the Plain Dealer with litigation for invasion of privacy, destroying the priest's ministry after he had paid his debt to society. With a projected $500,000 in legal fees if they identified Berthiaume, and were sued, the Plain Dealer editors drew on my reporting, duly credited, in a long Sunday commentary in March 1987. The editors treated me well; I respected the tough call they had to make. The piece called on Bishop Anthony Pilla to identify the priest. Pilla refused. Berthiaume went unnamed. But the diocese had a Pyrrhic victory: Survivors of other priests called the newsroom, leading to a powerful series by reporter Karen Henderson that made it worse for Pilla.

In 2002, as the Boston Globe reports caused other newsrooms to follow suit, the Plain Dealer finally identified Berthiaume, and reported that he had left the diocese after the 1987 coverage. As bishop of Joliet, Illinois, Imesch took him in. Berthiaume settled into a long stint as chaplain at Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital; Imesch removed him after the 2002 coverage. A lawsuit in 2001 had accused Berthiaume and a Cleveland priest whose rectory he shared of molesting a youth in the 1980s — making three lawsuits with six victims for the mystery priest.

Advertisement

What did the church gain in protecting Berthiaume?

"It is very difficult for someone who has served 12 years as chaplain to have the (newspaper) ruin whatever is left of his life," Imesch told The Associated Press.

Berthiaume's name surfaced in a 2006 deposition that Imesch gave in a case involving another priest. Imesch told attorney Jeff Anderson: "As far as I can remember I think Gary admitted to me that he had done it before the [1978] conviction."

Anderson: "If he had told you that he had committed the offense against the child, isn't that evidence of the crime?"

Imesch: "That's a job for the police. I'm not going to get involved in that. That's not my responsibility."

In the past, many states did not have laws mandating bishops or priests to report child abuse to authorities. But the sheltering, if not coddling, of serial sex offenders by bishops like Imesch who felt sorry for Berthiaume, with survivors an afterthought, is the snapshot of a parallel universe, clerical life as a protected, self-governing realm.

Berthiaume was laicized in 2007; Imesch died in 2015.

Tomorrow, Part 3. The Vatican.

[Jason Berry is the author most recently of City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300.]

*This story has been updated to correct the university in Spokane as Gonzaga University.