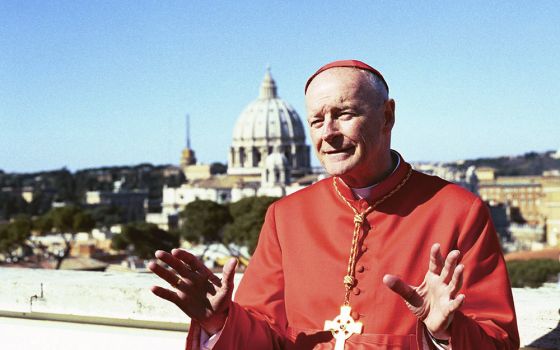

Bishops and priests attend Pope Francis' celebration of Mass marking the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul in St. Peter's Square June 29, 2018, at the Vatican. (CNS/Paul Haring)

It has long been understood by those who take a measured and thoughtful assessment of his papacy that the story of St. Pope John Paul II was sent off to the printer long before it was ready.

The narrative had not had time to mature, to incorporate the layers of complexity that marks us as truly human, to account for contradictions and flaws. The McCarrick report is the most persuasive evidence to date that the appellation "The Great" was applied too soon. In that regard, the report also serves as warning not to rush to conclusions about the abuse crisis itself.

John Paul II, confronted with the most damaging scandal the church faced in centuries, ignored the disturbing warnings from victims and from bishops entrusted with the care of the flock and instead embraced the adulation and counsel of serial predators. In doing so, he became not a figure of the courage that he persistently demanded of others, but the highest profile example of a corrupt hierarchical culture responsible for perpetuation of the abuse disgrace.

The editors of this publication do a great service to the church, and to sexual abuse victims, by asking the U.S. bishops to put the brakes on the John Paul II cult. It is, indeed, time to rein in the cult that has grown up around a garish superhero version of a pope.

The greatest value of the recent report, however, is not in establishing the weight of blame for the McCarrick debacle, though that is significant. Its greatest value is establishing that for all of his legendary achievements on the international front, at home John Paul II was a rather pedestrian member of a culture that has deep underlying maladies that became manifest in the abuse crisis. What he did, which warrants condemnation today, was not extraordinary at the time. He did what was expected of one deeply invested in and rewarded by the culture. He protected it at all costs, ignoring credible and impassioned warnings about McCarrick and another of his favorites, Marciel Maciel Degollado, founder of the corrupt Legionaries of Christ. The costs have been globally destructive of the church's credibility and authority.

We all wish John Paul had acted more humanely and less arrogantly toward those issuing the warnings and toward the victims. It would have spared the church a great deal of pain in the short run. But it only would have delayed the inevitable unraveling of a culture that is all male, allegedly celibate, deeply secretive, highly privileged, and based in no small measure on centuries of flawed thinking and anthropology about women. It was destined to run into trouble.

Look around the U.S. episcopal landscape during the John Paul II era and notice stunning similarities to that pope's example. Take Cardinals Anthony Bevilacqua of Philadelphia, Roger Mahony of Los Angeles, Bernard Law of Boston, Archbishop Rembert Weakland of Milwaukee, to name a few. All of them, in different ways, were admirable figures, often remarkable promoters of the social gospel and advocates in the wider culture for truth and justice. But all of them, in varying degrees, were, like the pope who elevated the cardinals among them, subservient in the end to the culture that gave them status and privilege. Even Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago, who was the first to institute reforms and establish a review board, was known to have protected abusive priests, shielding them from prosecution and transferring them among assignments.

The point is that none possessed the prophetic voice that would have made a difference and revealed the ugly truth of the matter. They all, some in more egregious ways than others, engaged in a cover-up and in a ruthless disregard for victims and their families. Their example was repeated endlessly through the ranks of the hierarchy.

Remaking rules and statutes and seeking accountability will satisfy some of the failings. Those actions, however, are only a small step on the way to the truth of the matter, a truth that in its fullness lies in transformation of the culture, not merely changing statutes.

The wisdom about where to go from here is out there. Consult the thoughts of inactive priest Thomas Doyle or Jesuit theologian Fr. James Keenan. Reference the writings of the late Richard Sipe or the work of Patrick Wall, both former members of the Benedictine order who turned into tireless advocates for abuse victims. Don't skip over what I consider one of the deepest insights offered in the process of searching for a way forward, the thoughts of Sr. Carol Zinn, on the need for transforming relationships before retooling institutional structures.

Exhaustive evidence of the depth and breadth of the corruption exists in the files of bishopaccountability.org, one of the most extensive repositories of abuse scandal materials extant.

The above represent just a few notables among many valuable resources available and largely ignored by members of the hierarchy when dealing with the scandal.

Advertisement

The McCarrick report is an extremely important step in ascertaining the truth, and one that could lead to even more essential truths. But it is only a step and, like almost all of the others since this scandal first surfaced in 1985, it was inspired by yet one more round of bad news served up either by news media investigations or legal proceedings.

The hierarchical culture has been publicly humiliated and chastised. Its mystique is gone, its authority and credibility are in tatters. In the breach, the role of the Catholic Church in the United States is increasingly fashioned by those who possess wealth and their organizations that lie beyond the control of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Those of us in the pews are left to ask: Where is the authority? Whose voice do we follow?

The steps not yet taken involve much deeper, interior work on the part of those still greatly invested in and rewarded by the culture than they've yet been willing or able to face. They must be willing to ask themselves fundamental questions about the meaning of ordination, the role of the ordained in the larger community, the consequences of prohibiting women from the realm of the ordained, the role of privilege and secrecy in church governance. They have to decide whether the model for bishops is prince or servant, and what that decision portends for their credibility and leadership in the future.

[Tom Roberts is former editor of NCR.]