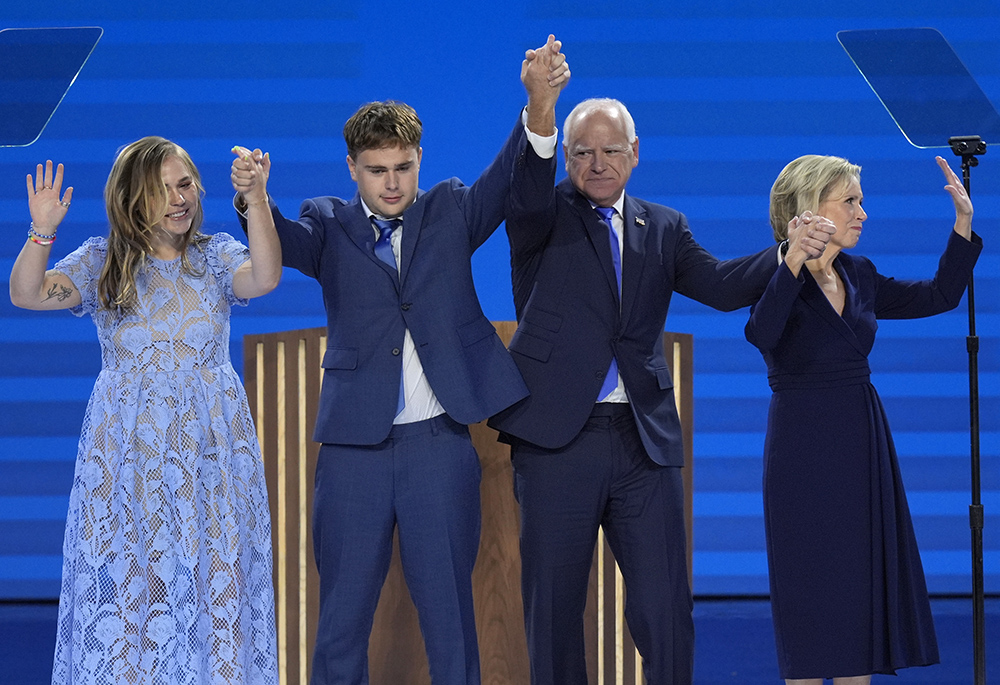

Democratic vice presidential nominee Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, second from right, poses with his wife Gwen Walz, from right, son Gus Walz and daughter Hope Walz after speaking during the Democratic National Convention, Aug. 21 in Chicago. (AP photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Vice President Kamala Harris ended her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention Aug. 22 with words that have become something of a requirement for U.S. political speeches: "God bless you, and may God bless the United States of America."

But not every speaker at the DNC gave that final blessing. North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, who introduced Harris, did not. Neither did Maya Harris, the nominee's sister, who spoke before Cooper. Nor did Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, earlier in the evening.

Perhaps not coincidentally, former U.S. Rep. Adam Kinzinger of Illinois did end with "God bless you." He is a Republican who supports Harris over Donald Trump. Indeed, at the Republican convention last month in Milwaukee, a speech not ending with mention of the Divine was the exception.

Not so at the DNC. The regular skipping of the previously required spiritual sendoff signaled a broader shift from explicitly religious rhetoric to the language of values, which took center stage. Once the vocabulary of conservative culture warriors, moral language is now the lingua franca of liberals and progressives, with Democratic convention speeches peppered with references to family values such as "freedom," "patriotism" and "character."

On the convention floor, delegates also were speaking the language of values. "When I'm looking at candidates I support, I look at their values, like compassion and tolerance," said Amanda Farías, majority leader of the New York City Council, who credits her Catholic faith with her own career in public service.

New York City Council members Carlina Rivera (left) and Amanda Farías say their Catholic faith informs the values that mesh with their Democratic politics. (NCR photo/Heidi Schlumpf)

Fellow New York council member Carlina Rivera also said she appreciated hearing words like "God" and "family" at the convention. "I think those are words that have been somewhat monopolized by the Republican Party and are words that we should embrace that are important to us as values," she told NCR.

Terri Wenkman, a registered nurse and delegate from Wisconsin, said valuing "doing unto others" and caring for the least of these comes directly from her Catholic faith. "That is why I identify as a Catholic and Christian, as well as a Democrat."

But she said she sometimes struggles with how to articulate those values, especially when talking with one-issue Catholics.

To help educate delegates and others about how to speak to a broad audience of voters, the DNC's Interfaith Council held a workshop during the convention on the topic of "values-based language."

"It's a myth that you have to choose between religious or nonreligious voters," Sarah M. Levin, co-chair of the DNC's Interfaith Council, said at the Aug. 22 meeting. "We don't come together to share theology. It's about coming together around shared values."

To be sure, there were still plenty of references to God and religion at the convention. Harris mentioned "faith" twice in her acceptance speech. Throughout the convention, Religion News Service national reporter Jack Jenkins kept a running commentary on social media of references to Scripture, the Divine and religion or spirituality.

But the speeches throughout the week clearly attempted to reclaim the language of values, even "family values," a phrase co-opted by the Republican Party since the 1990s.

Harris described how her neighbors growing up "instilled in us the values they personified — community, faith and the importance of treating others as you would want to be treated, with kindness, respect and compassion."

Democratic presidential nominee and U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris takes the stage during the Democratic National Convention at the United Center in Chicago on Aug. 22. (OSV News/Reuters/Brendan Mcdermid)

She urged Americans to "show each other and the world who we are and what we stand for: freedom, opportunity, compassion, dignity, fairness and endless possibilities."

Vice presidential nominee Tim Walz also spoke about the values he learned growing up in a small town. "That family down the road, they may not think like you do, they may not pray like you do. They may not love like you do. But they're your neighbors. And you look out for them. And they look out for you. Everybody belongs. And everybody has a responsibility to contribute."

But perhaps nothing said "family values" more than Walz's son, Gus, being moved to tears during his father's introduction on Aug. 21. And nothing boosted the Democrats' argument that the GOP is no longer the party of family values than some conservative commentators mocking Gus for his emotion.

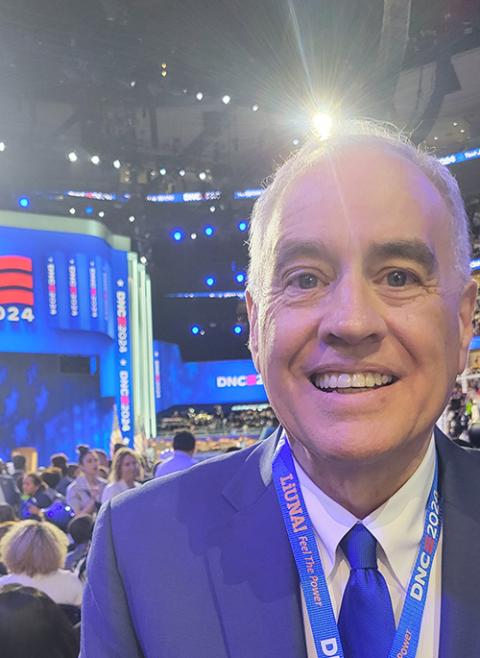

New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli believes the Democratic Party did a better job of values messaging at this year’s convention in Chicago. (NCR photo/Heidi Schlumpf)

New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli believes his party is doing a better job on values messaging at this convention. "It's a very inclusive message in terms of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation," he told NCR from the convention floor. "And it's not only looking out for those less fortunate, but also understanding that the key to success in America is having a strong middle class."

DiNapoli said the Democratic Party speaks to his values formed by his Catholic faith. "In a year like this, when you see the kind of agenda the Republicans are putting forward, it's certainly not consistent with my view of how humankind should be treating one another."

Lester Aponte, who grew up in Puerto Rico and now lives in California, said his years of Catholic education taught him to be "intellectually curious." He is especially concerned about discrimination against the LGBTQ community and says he believes the party is doing a better job of communicating its values.

"I think I've heard a lot of that this week," he said. "I feel a real change and a sense of excitement. I'm hopeful that we're connecting with people."

A move toward values language makes sense, given the 30-year trend of secularization in the United States, in which 20-30% of Americans now identify as nonreligious in some way, political scientist Juhem Navarro-Rivera said at the Interfaith Council meeting.

Even religious people attend church less frequently, said Navarro-Rivera, political research director and managing partner at Socioanalítica Research and senior fellow at the Institute for Humanist Studies.

This demographic shift has political implications, he said. "People are not just leaving their religions, they're changing their beliefs," he said. "And when it comes to politics, it's Democrats who are at the head of this change. The Republican coalition has become more Christian nationalist and the Democratic coalition has become more ecumenical and religiously diverse."

U.S. flags and balloons are seen after Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential candidate, gave her speech during the Democratic National Convention, Dec. 22 in Chicago. (OSV News photo/Reuters/Brendan Mcdermid)

Navarro-Rivera noted that the term "evangelical" has become more of a political label than a religious one. Yet that ideology doesn't represent all Christians. "I don't think there's been enough push back" from progressive Christians, he said.

Among the atheists, agnostics and "nones" today are what Navarro-Rivera termed "cradle secularists" who were raised by nonreligious parents. "This is a new phenomenon we need to talk about because it involves younger voters," he said. "A lot of people are not even used to that kind of faith language."

Navarro-Rivera sees the changing demographics as an opportunity to strengthen the party through messaging that speaks to both religious and nonreligious people.

"We shouldn't despair that this diversity is happening," he said. "Even though they have different views of faith and the supernatural and God, they do care about the same issues."

'When I'm looking at candidates I support, I look at their values, like compassion and tolerance.'

—Amanda Farías, majority leader of the New York City Council

Using moral language is a strategy to communicate effectively with nonreligious voters while not simultaneously alienating religious ones, said Isaac Wright of the Rural Voter Institute.

"We found that moral language is every bit as effective as faith-based language with both faith voters and secular voters," he said at the Interfaith Council meeting. "Moral language is something that connects with all sects, and persuades people and moves them."

Democrats need to speak about their convictions and beliefs in an authentic, yet inclusive, way, he said. And people are hungry for values-based language, such as references to fairness, community, hard work, self-determination and a sense that "we're in this together."

Advertisement

When Democrats do use explicit faith-based language, they should respect that not everyone shares their same beliefs, especially since sociologists trace the rise of the "nones" to the rise of the religious right, he said.

Levin recommended personalizing, not universalizing. For example, rather than say, "Faith compels us to …" say "My faith compels me to …".

"If it's personal to you, that's authentic, but be mindful not to exclude," she said. "It doesn't mean you have to hide your religious faith."

Wright said that moral language stresses what's right versus wrong, but does so using narrative, story or even "testimony," and he recommended that rather than focusing on the "cerebral side of policy," Democrats should talk about the real impact of policies.

"If we don't define our values, Republicans will."