Gerrit Punt, a student at St. Labre Catholic school on the Northern Cheyenne reservation, takes part in the school's Braves Ink printing program. (Tim Uhl)

Pope Francis calls us to become missionary disciples, and not "passively and calmly wait in our church buildings" with a pastoral ministry of mere conservation. He is calling us to the peripheries where the Gospel is most needed. Where are the peripheries of our church? On the Indian reservations.

As the superintendent of Montana Catholic Schools, I want to share the Native American Catholic school experience. Last spring, I invited a collection of Catholic school leaders to come to Montana in order to see these schools on the margins. Many people were interested but, ultimately, no one made the trip with me. I went anyway.

This is a disappearing margin, as the number of Catholic schools serving Native Americans continues to plummet. The best illustration of the reality of life on the reservations comes from the American Indian Catholic Schools Network. Brian Collier, director of the network, noted statistics that of all Native American children who start ninth grade, only 48 percent graduate from high school and only 1 percent earn a college degree. Native American graduation rates are the lowest of any ethnic/racial group in the U.S.

Native American reservations are high-poverty rural ghettos where people experience low life expectancy, poor health care, high rates of substance abuse, and widespread poverty. Yet the people persevere, find joy in their families, and work to maintain their cultures and languages, despite many challenges, almost all of which are brought on by the outside world.

St. Charles

My first stop was St. Charles Mission Grade School in Pryor, Montana, just 30 minutes outside of Billings, Montana's largest city at 100,000 residents. Many students and most teachers (including two Jesuit volunteers) travel from Billings every day. Located on the Crow reservation, Pryor is off a narrow two-lane highway cutting through rolling hills.

St. Charles is part of the St. Labre Indian School network, which has successfully raised money through direct appeals and has built up a strong base of supporters nationwide.

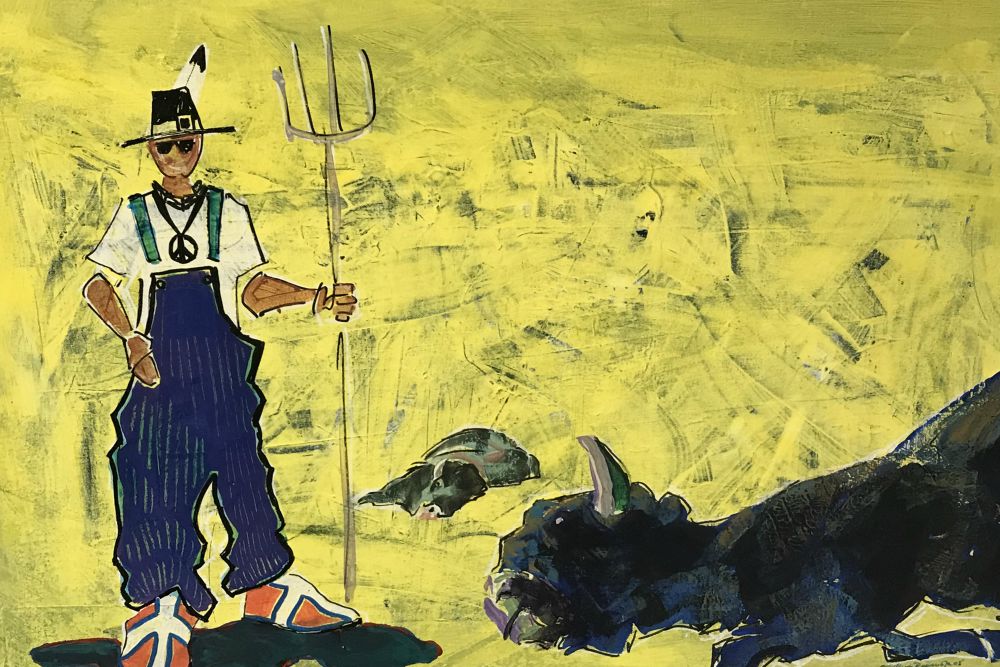

Detail from Henry Payer's "Here I Am ... Speechless," a 2008 painting in the Red Cloud Heritage Center's permanent collection (Tim Uhl)

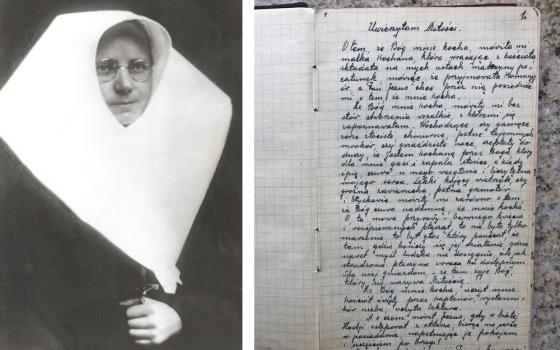

Principal Bambi VanDyke ushered me into the library to meet with the two religion teachers and Capuchin Fr. Randolph Graczyk, the pastor who has served there for 43 years.

The Capuchins have been committed to serving the seven Catholic parishes on the reservations of southeast Montana since 1926. Five years ago, the province examined all of its domestic and international commitments and decided to double down on its efforts in Montana while moving away from others.

Graczyk lives next to the church and has built a sweat lodge out back. He is a Crow language expert, writing a dictionary and authoring pre-kindergarten and kindergarten educational materials in Crow. It is estimated that without intervention, the Crow language will die in three generations. Graczyk is working to keep the traditions of the tribe and its language alive.

The two religion teachers have struggled with new religion materials produced by the Sophia Institute and weren't aware of the resources available. Graczyk argues that the program isn't culturally appropriate and doesn't account for the context of the students at St. Charles. He recommends I read Finding a Way Home: Indian and Catholic Spiritual Paths of the Plateau Tribes by Jesuit Fr. Patrick Twohy, so I order it immediately from my phone.

When I read it later, I understand what he meant. The book represents an attempt to make meaning out of Catholic practices carried out in the reservation context. Furthermore, Collier, who is a professor at the University of Notre Dame, told me that the only Catholic Indian mission schools to succeed and not face imminent closure were the ones that found ways to be culturally relevant to the populations they served.

Advertisement

When the meeting ends, I walk with VanDyke through the building, seeing many familiar faces. They have tried to establish a two-way immersion (Crow/English) program in the early grades, but the effort has stalled due to teacher turnover.

In 2018, the school suffered a significant decline in enrollment. Tuition is free and, as with many of our reservation schools, this serves as a reminder to all of our Catholic schools that even free tuition won't fill our classrooms. There is a variety of reasons for enrolling, and when something is off, enrollment can suffer. The trick is diagnosing what is wrong. VanDyke is trying to figure out what is wrong so she can solve the problem.

Pretty Eagle

I depart St. Charles and travel the hilly, rough road east toward St. Xavier. Like all these outposts in southeastern Montana, this church and school were originally Jesuit. Named after a local chief, Pretty Eagle Catholic Academy is another member of the St. Labre Indian School network and currently boasts two campuses — a dual-language preschool in Lodge Grass and a K-8 school in St. Xavier. The school was moved to the dormitory building a few years back when the original school burned down. Now the school is hoping for a capital campaign to build a new facility.

Pretty Eagle's enrollment is growing and healthy. Garla Williamson has been principal for 14 years. Committed to her own recovery from alcohol addiction, Williamson has brought a recovery group to parents but hasn't met much success.

"The dysfunction of alcohol and drugs impacts all part of our students' lives," she said. "It continues to impact their lives beyond school — how they communicate, how they grieve and how they live."

Williamson emphasizes culturally appropriate positive discipline as an antidote to the dysfunction and chaos that so many of the students experience at home.

A special feature at Pretty Eagle is the STEM/robotics component in the middle school. Jack Joyce, an award-winning teacher, has developed a partnership with Montana State University, which sends a professor and other resources at least once a month. We visited the computer-aided design class, which last year designed and built a new doghouse for Rex (the resident black lab). This year, students in the class are designing a new shed for the football equipment.

Joyce has also supported development of a robotics team, a drone club, and an active greenhouse set up in a broken-down school bus.

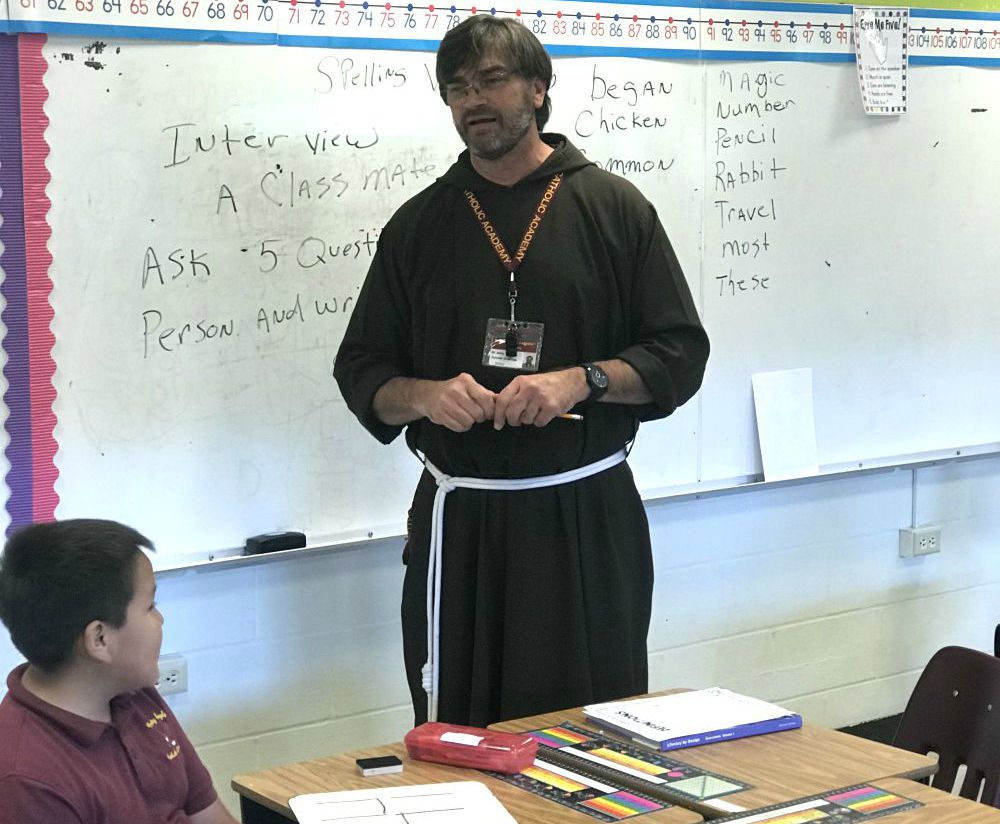

Capuchin Br. Jerry Cornish teaches fourth grade at Pretty Eagle Catholic Academy. (Tim Uhl)

St. Labre

Every time I drive onto the St. Labre campus on the Northern Cheyenne reservation, I'm struck by its similarity to a college campus. The school has built a couple of employee villages for staff housing. There are more than 100 staff members who live on campus in housing. They also have a dorm with 84 student residents, a group home, a health clinic and a variety of other community service programs.

Executive director of schools Crystal Redgrave and curriculum director Michelle Charlesworth take pains to show me their robust reading intervention programs. Literacy is their focus. With or without preschool, their students enter kindergarten behind their peers and Redgrave and Charlesworth are determined to design effective interventions.

St. Labre is proud of its cultural education programs. Students have opportunities to study the Crow and Cheyenne languages as well as cultural expressions like beadwork, art and drumming. The school embraces Native traditions as well as Catholic identity.

Redgrave was proud to show me the Braves Ink production facility, which produces logo wear and T-shirts for the school and surrounding businesses. Students worked together to fulfill orders in this student-run venture.

Red Cloud

Having grown up under the tutelage of a father fascinated by Lakota history, I was excited to walk in the footsteps of Chief Red Cloud and Black Elk. Upon my late-night arrival to Red Cloud School, I was ushered into a guest suite in the original Holy Rosary building built from a personal donation from St. Katharine Drexel. The school was founded by Jesuits in 1888 at the request of Chief Red Cloud.

Nicholas Black Elk's grave in St. Agnes Catholic Cemetery in Porcupine, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Reservation (Tim Uhl)

On the main campus, there are three schools (elementary, middle and high school), with a large number of Jesuits and volunteer teachers through Creighton University's Magis Catholic Teacher Corps, a postgraduate service teaching program. Most of the teachers are encouraged to obtain a commercial driver's license so they can drive one of the eight bus routes. All told, the teacher-drivers cover 1,000 collective miles daily to enroll their 600 students.

I met Jesuit Fr. George Winzenburg, the longtime president. He was quick to describe the mission of the schools as well as the challenges, such as raising money and retaining teachers. Facing their own dwindling numbers, the Jesuits decided to close the St. Francis School in Rosebud. For apostolates like Red Cloud, the void left by the Society of Jesus will need to be filled by community members.

My tour guide pointed out a display about Black Elk in the Holy Rosary Church lobby, the parish where Black Elk served as a catechist. A Vatican investigator has been onsite to investigate possible miracles.

Black Elk's cause for sainthood — while popular among U.S. bishops — remains controversial on the reservation because Black Elk continued to practice both Indian and Catholic traditions late into his life, not unlike the early disciples who incorporated local traditions into their own practices.

[Tim Uhl is superintendent of Montana Catholic Schools and is the creator of Catholic School Matters, a newsletter and podcast.]