Many images of Blessed Archbishop Óscar Romero adorn the office of Tony Arteaga, shown here with his wife, Delmy, at Los Angeles’ Dolores Mission Parish. (NCR photo/Dan Morris-Young)

When Tony Arteaga recounts the scene unfolding shortly following the assassination of Blessed Archbishop Óscar Romero, the trauma, chaos, confusion and horror are palpable.

A crew member of a television outlet in San Salvador, El Salvador, Arteaga was not working that day — March 24, 1980 — but when word of the shooting reached him, he rushed to the clinic where Romero's body had been taken.

Arteaga vividly recalls seeing the archbishop's body on a metal stretcher, and how the lighting he struggled to position for TV cameras generated static electricity that shocked anyone who came close.

"There were at least 30 reporters crowded into the room," he told NCR through an interpreter.

The profundity of what had just happened could hardly be grasped, said Arteaga, now a member of Dolores Mission Parish in Los Angeles. "I was crying, and I could not believe that Monseñor Romero had been killed."

A car had pulled up to the open doors of the chapel of Divine Providence Hospital in San Salvador while Romero was presiding at a memorial Mass. The car carried a marksman who placed a shot near Romero's heart.

The assassination had clear links to death squads associated with the ruling junta, according to a United Nations truth commission established in 1992 to investigate killings and human rights violations following the end to El Salvador's 12-year civil war.

Many argue that Romero was one of the few people in the country who could have been a bridge between the country's sharply divided elements of power, including the ruling junta, oligarchs and leftist rebel forces.

The 1980-92 civil war led to the deaths of an estimated 75,000 unarmed Salvadorans, most of them poor.

Romero's murder widely crushed hopes for compromise or reforms, including the hopes of the then-24-year-old Arteaga.

"You just can never imagine something like this could happen," Arteaga said. "Óscar Romero was our hope. He symbolized hope for our community. We could feel that war was coming on and he was our hope. Through him was our last avenue toward a possible peace."

In the aftermath of Romero's death, "a lot of people just lost their fear, lost their fear of fighting," Arteaga recalled, "because they just so much wanted justice for what happened to him."

Advertisement

It soon became illegal, he said, "just to have a Bible, or to attend a Bible study. To get together with a prayer group was considered a criminal activity. And you could not carry a photo of Óscar Romero or have one in your home."

"It was so hard," he said. "I could not believe that things had gotten to this point. It awakened my conscience to just how bad things were. Even in media work, it was hard to understand how bad things had become."

Romero's murder, Arteaga continued, "helped me understand. I started to notice so much corruption, just so much corruption."

He admitted that "no one trusted the local press," and that "only the international press" was relatively reliable. That is, in addition to Romero himself.

Arteaga counts himself among the thousands of Salvadorans who were devoted listeners of Romero's often-lengthy homilies and talks that were broadcast over the archdiocesan radio station on Sundays. In them, the archbishop would detail killings and atrocities, citing victims' names and perpetrators.

According to Central America experts Linda Cooper and James Hodge, the broadcasts were "the most popular program in the country, with nearly 75 percent of the rural population and 50 percent of the urban population listening in — along with the U.S. Embassy."

On the day before his slaying, Romero spoke directly to members of the army, urging soldiers to stop killing their fellow citizens and telling them they were not obligated to follow orders than violated their consciences.

Like the vast majority of fellow Salvadorans, Arteaga felt a closeness and kinship with Romero. Unlike others, however, he actually shook hands and spoke with the churchman.

"After Mass was done," he said, "I would wait and shake his hand and greet him."

Arteaga's memories of Romero's funeral are vivid as well.

Again, he had not been assigned to cover it, but attended on his own, using his press credentials to be allowed into the upper terrace areas of the cathedral.

"I was up there looking at all the people, the thousands of people who had come out," he told NCR, "and then from the National Palace across the way, they were shooting at people. You could see the smoke from the rifle fire."

Panic ensued. "There was a stampede of people trying to get into the cathedral for shelter," he said. He knew his mother was in the crowd.

"I was trying to get down from where I was, but people were trying to get up to protect themselves. When I finally got down, I saw bodies on the ground, mostly women. It looked like they were dead.

"I was crying. I thought one of them was my mother. I just kept looking for her."

The image of "lots and lots of shoes" abandoned by persons fleeing the scene sticks in his mind.

He made his way to his aunt's home not far from the cathedral, praying his mother had gone there. She had. "Her arm was bruised, but she was OK."

Abandoned shoes are seen outside the San Salvador Cathedral after the massacre at Archbishop Óscar Romero's funeral Mass on March 30, 1980. (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

"There was so much fear. Nobody knew what was going to happen next. People were very afraid that there would be another mass massacre at the cathedral," Arteaga said.

Now a father of three and grandfather of two, Arteaga made his way to the U.S. and Los Angeles in 1983 and was soon involved in efforts to aid immigrants and refugees, notably from El Salvador.

Through that sanctuary movement work he met Jesuit Fr. Michael Kennedy who had lived in war-ravaged El Salvador from 1980-83. When Kennedy was appointed Dolores Mission pastor in 1994, Arteaga went along.

The pair worked closely again in relief efforts for El Salvador following two devastating earthquakes in early 2001.

Today, Arteaga and his wife, Delmy, are deeply enmeshed in the parish. Arteaga himself has coordinated security for the parish's Guadalupe Homeless Project for the last 18 years. The program provides daily overnight respite to roughly four dozen men on the parish campus.

His role eclipses rules enforcement, however, according a parish staff member. "Tony also listens to the men's problems, prays with them, counsels and shares wisdom with them, and reaches out to those who are sick," she said.

His small office makes his devotion to Romero obvious. Some of his Guadalupe Project clients have even shown appreciation by creating drawings and images of the archbishop for him.

For Salvadorans, the Arteagas say, the importance of Blessed Romero's expected canonization cannot be overstated.

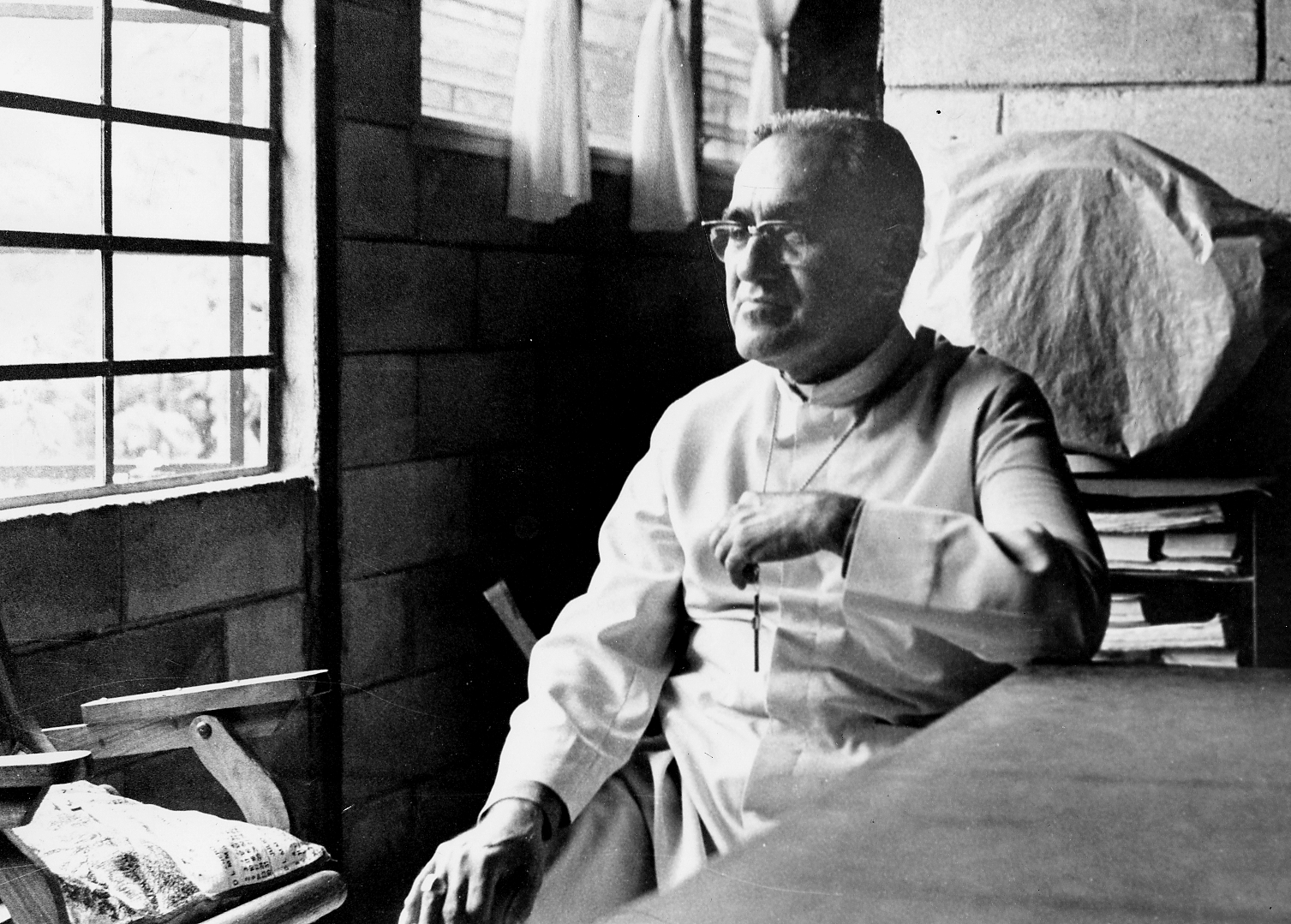

Blessed Óscar Romero in Ateos, El Salvador, in 1979 (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

"It is truly amazing for El Salvador," said Delmy, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1991 and met her future husband through her brother, whom Tony had aided in El Salvador after the civil war began.

Tony Arteaga was able to attend Romero's 2015 beatification in San Salvador.

Veneration of the slain martyr is ubiquitous at Dolores Mission. Roughly a quarter of its members have Salvadoran roots. The church interior highlights a side wall poster of Romero.

Annually, the congregation marks the March 24 anniversary of the archbishop's slaying. This year, it will begin with a candlelight procession around the block where the church is located. A 5 p.m. Mass will be followed by a reception in the parish plaza featuring traditional canela tea and pan dulce.

[Dan Morris-Young is NCR's West Coast correspondent. His email is dmyoung@ncronline.org.]

We can send you an email alert every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.