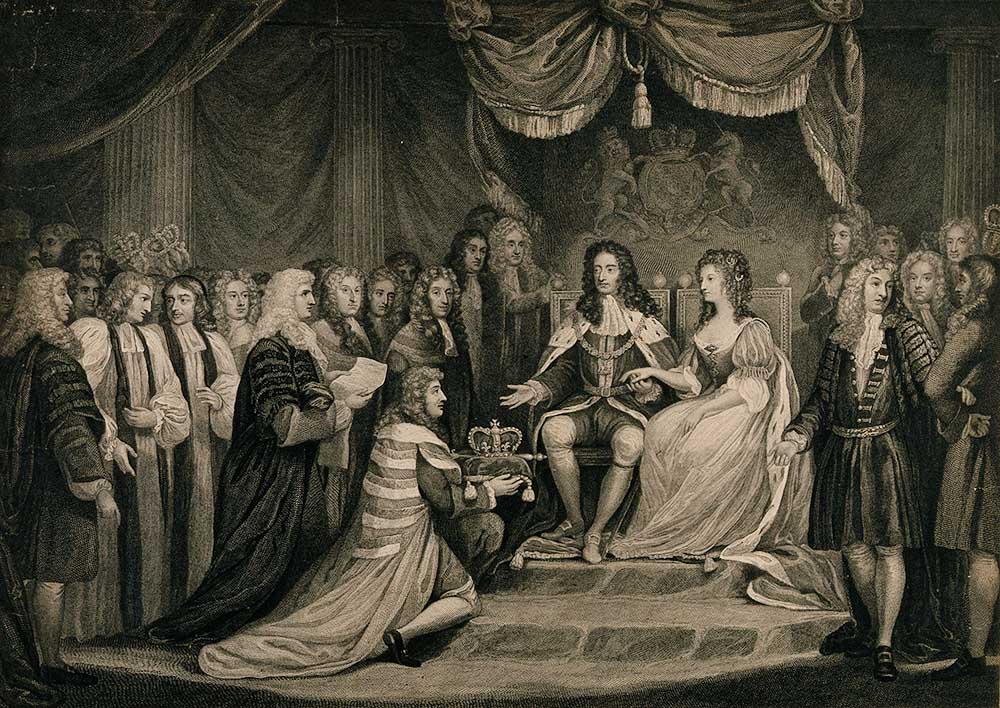

William of Orange and his wife, Mary, are presented with the English crown in 1688, as depicted in a 1790 engraving. (Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Collection)

On Monday, I began my review of Michael Breidenbach's important new book Our Dear-Bought Liberty: Catholics and Religious Toleration in Early America. And I ended with the questions: Does he have what he thinks he has? Does his theory about Catholic ideas and experience informing the separation of church and state in the U.S. Constitution work? Were conciliarism, Gallicanism and the negotiations over the exact wording of oaths of allegiance to the English monarchs historical precursors of the First Amendment? Must the historiography of the founding era be reworked?

The short answer is: yes and no. Breidenbach's research unearths information about the influence of conciliarist ideas on someone like Bishop John Carroll that I had never encountered before. Carroll was not only trained by the Jesuits, the archenemies of the conciliarists, but he had become a Jesuit! The anti-Roman attitudes in his correspondence always seemed more likely to stem from the suppression of the Jesuits than from any affinity with conciliarism.

Yet, as Breidenbach demonstrates, he was not only familiar with conciliarist and Gallican ideas, he was willing to employ arguments drawn from those sources when it suited his purposes.

Similarly, the research into the negotiations about loyalty oaths is fascinating, but one suspects it was less ideological than Breidenbach allows. Whatever else they were, 17th-century Catholics were not Kantians, and so they knew that the teaching of the church had to be applied to concrete circumstances using prudential judgment. The sage of Konigsberg and his categorical imperative were no part of their intellectual and moral calculations. What Breidenbach tends to cast as an "antipapalist" limitation on papal prerogatives might be the best arrangement possible in difficult, even hostile, circumstances.

Some assertions simply do not make sense. "The pope's suppression of the Jesuits had demonstrated the devastating effects of being in a state of dependence on an arbitrary power — one that had terminated the Jesuits' constitutions and even their existence by his singular will," Breidenbach writes.

But the Jesuits had been brought into existence by papal bull, and the papal bull suppressing them was forced upon the pope, and came only after the Bourbon monarchies had already suppressed the order in Portugal, France, several Italian states and the Spanish empire. There was resentment against Clement XIV for the suppression, of course, but the conclusion Breidenbach draws is far-fetched.

What is more, the interplay of religion was far more complicated than Breidenbach lets on. The claim in Regnans in Excelsis that the pope had the power to dispense a Catholic subject of a Protestant monarch from their allegiance to that monarch was never pushed or asserted throughout the Stuart dynasty, at least not with any force. Robert Bellarmine may have included it in a treatise, but so what?

In the meantime, Charles I married a Catholic, Henrietta Marie of France, as did his son, Charles II, who married Catherine of Braganza from Portugal. Charles II reputedly converted to the ancient faith on his deathbed. Catholics, disenfranchised to be sure, were tolerated so long as they kept their faith private and quiet. The greater concern of the Stuart Restoration was to maintain peace between the Calvinist Puritans and the Church of England.

Advertisement

Yes, the Glorious Revolution in 1688, deposing the Catholic James II, was obviously motivated by anti-Catholic feeling, and anti-Catholicism would be part of the effort to create a distinctly British consciousness after the 1707 Act of Union united Scotland and England into one Parliament. But anti-Catholicism became ritualized, via celebrations of Guy Fawkes Day, or episodic, as in the 1780 Gordon riots. The comprehensive anti-Catholicism of the reign of Elizabeth did not characterize the century of Stuart rule.

The disjunction of temporal and spiritual realities can be seen as well in the reign of Innocent XI, pope from 1676 until 1689. His spiritual sensibilities did not prevent him from making common cause with the Calvinist William of Orange in his wars against Catholic France. When William landed at Torbay on Guy Fawkes Day in 1688 — "Well, doctor, what do you think of predestination now?" William quipped to the Anglican chaplain accompanying him, the future Bishop of Salisbury Gilbert Burnet — to depose the Catholic James II, Innocent XI refused to come to James' aid.

At times, Breidenbach actually seems to invoke an incident that cuts both ways, for and against his argument, but he overemphasizes one side of the case and aggressively simplifies important complications. For example, he makes much of the fact that the first bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States, Samuel Seabury, had gone to Britain and was ordained not by the Anglican bishop of London who had exercised jurisdiction over the American colonies. Instead, he was ordained by three Scottish bishops, John Skinner, Robert Kilgour and Arthur Petrie, all of whom were nonjurors, that is, they had refused to take the oath of allegiance to King William and Queen Mary.

Michael Breidenbach, author of "Our Dear-Bought Liberty" (michaelbreidenbach.com)

"For Episcopalians, this circumvention of the British Parliament ensured that Bishop Seabury's powers were not temporal in nature or derived from temporal sources, but were instead — as the pro-Episcopal Americans had promised — purely spiritual faculties," Breidenbach writes, adding, "The nonjuring tradition was, as later American Episcopalians noted, an important precedent for the American revolutionaries."

In a passing reference he notes, "Although Americans rejected the residual Jacobitism of the Scottish nonjurors, they adopted the nonjurors' arguments about the juridical separation of church and state."

You don't say! The nonjurors did not refuse to pledge their loyalty to William and Mary because they were early advocates of church-state separation. They were defending the right of the legitimate, and Catholic, monarch James II.

This is important because Breidenbach's argument relies heavily on the supposed Gallican influence on the Carrolls, both Charles the Signer (of the Declaration of Independence) and John the bishop. But Gallicanism did not seek to separate spiritual and temporal realities. It sought to create a national church in which the church was subservient to the king.

Some of the Gallicans' arguments may have been serviceable to the Americans, but a historian must take pains to show how different the historical and ideological climate had become.

In his book Marlborough: His Life and Times, Winston Spencer Churchill writes:

To understand history the reader must always remember how small is the proportion of what is recorded to what actually took place, and above all how severely the time factor is compressed. Years pass with chapters and sometimes with pages, and the tale abruptly reaches new situations, changed relationships, and different atmospheres. Thus the figures of the past are insensibly portrayed as more fickle, more harlequin, and less natural in their actions than they really were. But if anyone will look back over the last three or four years of his own life or of that of his country, and pass in detailed review events as they occurred and the successive opinions he has formed upon them, he will appreciate the pervading mutability of all human affairs. Combinations long abhorred become the order of the day. Ideas last year deemed inadmissible form the pavement of daily routine. Political antagonists make common cause and, abandoning old friends, find new. Bonds of union die with the dangers that created them. Enthusiasm and success give place to resentment and reaction. The popularity of Governments departs as the too bright hopes on which it was founded fade into normal and general disappointment. But all this seems natural to those who live through a period of change. All men and all events are moving forward together in a throng. Each individual decision is the result of all the forces at work at any given moment, and the passage of even a few years enables — nay, compels — men and peoples to think, feel, and act quite differently without any insincerity or baseness.

This sense of the "pervading mutability of all human affairs" is what is missing from Breidenbach's account. It is not the historical figures, but the ideas with which they worked, that emerge from his account "more harlequin." The ideas are given an ideological construct and persistence that minimizes or ignores the practical nature of the circumstances upon which those ideas were employed.

A 1763 portrait of Charles Carroll, who would become the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence (Yale Center for British Art)

It was the unique, pluralistic, revolutionary and opportunistic circumstances that confronted the Founding Fathers that proved decisive. They trusted Catholics like Charles and John Carroll because they had proven themselves trustworthy, because they were "gentlemen" like themselves, men of means and of learning. Non-sectarianism, if not actual secularism, had become a fact of life in the Continental Army as well as the Continental Congress.

If ideas drawn from the conciliarist tradition sounded akin to ideas drawn from Lockean or country Whig or classical republican ideas, at least on the surface, the drafters of the constitution, politicians all, felt no need to dig below the surface to find examples of philosophic bedrock that were less compatible.

Breidenbach's work, however, is fertile and invites scholars of the period to go back over their own work. One question that emerges from his account of the American founding would be: Were there Protestants who cited the Catholic conciliarist arguments, saying, "Even the Roman Catholics believe church and state should be separated," and was that persuasive?

Some who drafted the Constitution wanted the federal government to stay far from religion because they did not want any interference in their state establishments. My home state of Connecticut did not disestablish the Congregational church until 1818 and in nearby Massachusetts, the Congregationalists maintained their establishment until 1833. What role, if any, did the arguments Breidenbach cites play in the legislative discussions in such states?

Other questions will emerge as scholars bring what he has discovered into dialogue with the extant historiography of the periods he surveys.

This book, then is required reading for anyone who wants to delve deeply into the American founding and how it came to achieve the constitutional separation of church and state that has so shaped our culture and society.

Breidenbach's achievement is large, my many misgivings notwithstanding. He has opened up a new line of inquiry that can't be ignored and must be engaged, even if some of his conclusions will be refuted. That is no small accomplishment about one of the most studied epochs in American history.