(Julie Lonneman)

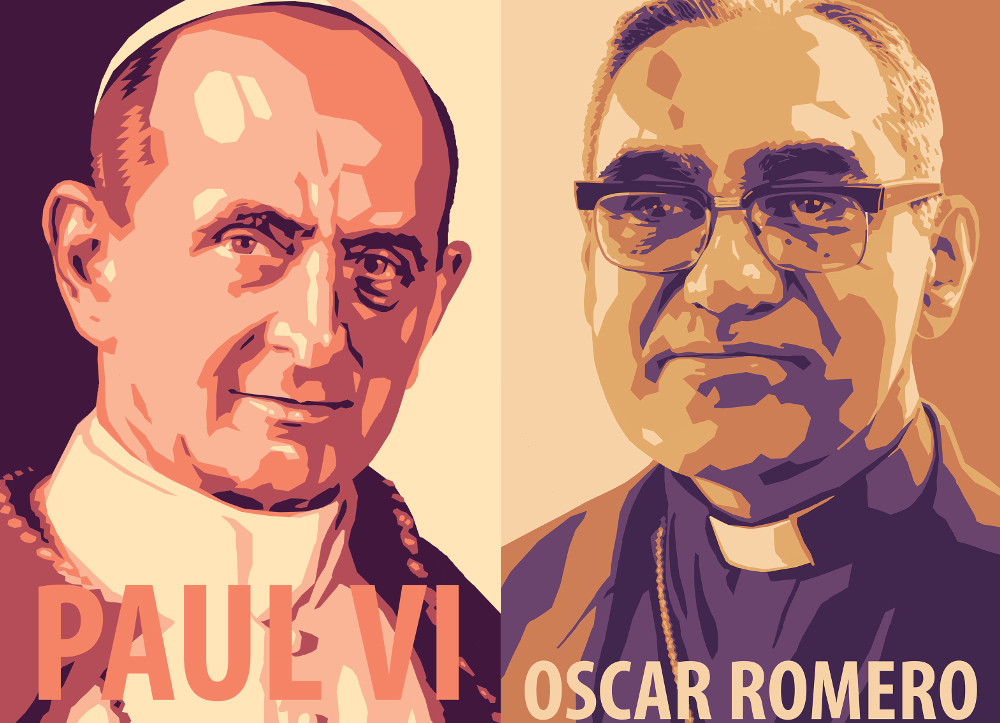

The significance of the canonization of Archbishop Óscar Romero cannot be underestimated as the bridge Pope Francis needs to convey a universal church trapped in the past toward a future that will purify it and align it with the global poor. And the joining of Romero and Pope Paul VI is no mistake or public relations ploy to balance a radical with a traditionalist. Remarkably, these two saints shared a martyrdom that built the bridge that supports a single trajectory, inspired by the Holy Spirit, that will renew the church and reveal again the mystery of Jesus as the engine of history. It is a thrilling story, and some key figures helped it happen.

When Romero was murdered in 1980, American Jesuit Fr. James Brockman saw the urgent need for an accurate biography of the slain archbishop of El Salvador. Brockman, former editor of America magazine, knew that Romero had been the focus of intense controversy during his brief time as archbishop. He also knew that despite the near-unanimous acclamation throughout Latin America that Romero was a saint, revisionists were already at work to contain his impact. His critics argued that this pious, conservative prelate had been duped by left-wing radicals during a dangerous drift toward Marxism sweeping Latin America. His assassination had been the tragic but predictable result of his meddling in politics, and the abdication of his primary spiritual role as a bishop.

In 1982, to counter these lies, Brockman published the first version of a definitive biography documenting Romero's three years as archbishop. He was aided by Romero's own meticulous paper trail preserving every official statement, homily, pastoral letter, the minutes of every meeting he attended, and his correspondence with government officials, his fellow bishops and the Vatican.

Updated in 1989, the book was supplemented by personal diaries in which Romero anguished over the growing violence in El Salvador by state security forces, death squads and opposition groups that claimed hundreds of innocent lives in the lead-up to the country's brutal 12-year civil war (1980-92).

Romero endured constant vilification in the media and subversion by four of the country's bishops aligned with the government and the country's wealthy elites. The papal nuncio sent a steady flow of negative reports to his superiors in Rome, accusing Romero of promoting so-called "liberation theology" and supporting violent revolution.

Romero defended his pastoral leadership by citing the Second Vatican Council and the application of its principles to the lived reality in Latin America by its bishops, who had met with Pope Paul VI at Medellín, Colombia, in 1968, where they proclaimed "God's option for the poor" and challenged the entrenched structural injustices that were causing widespread poverty and violence in the region.

Romero found further support from Paul VI's 1975 exhortation on evangelization, Evangelii Nuntiandi, which strongly affirmed liberation from oppression as integral to the church's mission. Despite death threats, pressure from Rome and the flow of arms from the United States to support the military against a perceived communist insurgency, Romero remained a faithful shepherd to his beleaguered flock until his death on March 24, 1980, while saying Mass in a hospital chapel in San Salvador.

Canonization holds up heroes of faith who confront us with what theologian Johann Baptist Metz called the "dangerous memory" of the crucified and risen Christ, who interrupts history in every generation to summon disciples to hear God's Word and keep it.

Nine years later, six members of the faculty at the Central American University in San Salvador, their housekeeper and her daughter were murdered by elite, U.S.-trained Salvadoran soldiers. A central target of the assassins was Jesuit Fr. Ignacio Ellacuría, a brilliant apologist for the martyred Romero as a good shepherd to his church, even at the cost of his own life.

Not present on campus by chance during the executions was Jesuit Fr. Jon Sobrino, who took up the task of extending the logic of Romero and Ellacuría's witness to a church deeply reluctant to acknowledge the kairos moment these martyrs had revealed.

Another crucial witness arrived in San Salvador in 1990 after the campus murders. American Jesuit Fr. Dean Brackley remained on the faculty of Central American University for the rest of his life, welcoming thousands of North American pilgrims and college students, daring to remind them of U.S. responsibility for so much of the violence in Central America, and for the desperate surge of refugees fleeing north.

Before his death from pancreatic cancer in 2010, Brackley, in an interview with NCR, prophetically gauged the importance of Romero's then-stalled canonization:

One has to suspect that if Romero were not a bishop, he might have an easier road to canonization, because not everyone in the Catholic hierarchy is comfortable with presenting him as a bishop to be imitated. …

Romero modeled the "church of the poor" that John XXIII called for at the start of the Second Vatican Council. The conferences of Medellin and Puebla fleshed out what that church should look like in Latin America. Romero followed that lead.

The message, though, is universally valid: The church will only be bearer of credible hope for humanity if it stands with the poor, with all who are victims of sin, injustice and violence. If we walk with them, as Romero did, we will embody the good news that the world so longs for. We do not need a church that invites us to hide from today's horrors, to escape the problems of this world, but to bear its burdens.

That is what Romero did, inspiring countless others to collaborate with him. This will invite persecution and misunderstanding but that is the fifth mark of the true church. Romero sought not what was best for the institution as such but what was best for the people. In the long run, that is what is best for the church, too. The institution that strives to save itself will lose itself. If it loses itself in loving service, it will save itself.

Advertisement

Like the 75,000 martyrs of the civil war in El Salvador, Brockman, Ellacuría and Brackley did not live to see our Latin American pope. But in the first hours after his election, Francis invoked Pope John XXIII's dream of a "church of the poor," saying he would like "a church that is poor and that is for the poor." It is now his turn to dream of such a church, shepherded by bishops who smell like their sheep, servant pastors and vibrant parishes filled with disciples who share the "joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties" of the modern world, especially young people on fire to live authentic lives.

But all this would only be an idea if Romero had not lived it and a cautious Paul VI had not suffered his own martyrdom of vilification from both progressives and traditionalists for insisting that church unity was more important than winners and losers after the council.

Canonization holds up heroes of faith who confront us with what theologian Johann Baptist Metz called the "dangerous memory" of the crucified and risen Christ, who interrupts history in every generation to summon disciples to hear God's Word and keep it.

Sts. Oscar and Paul did it in their time. Their witness is not just that they crossed the bridge of the paschal mystery to a different and necessary future, but that they are inviting us all to follow.