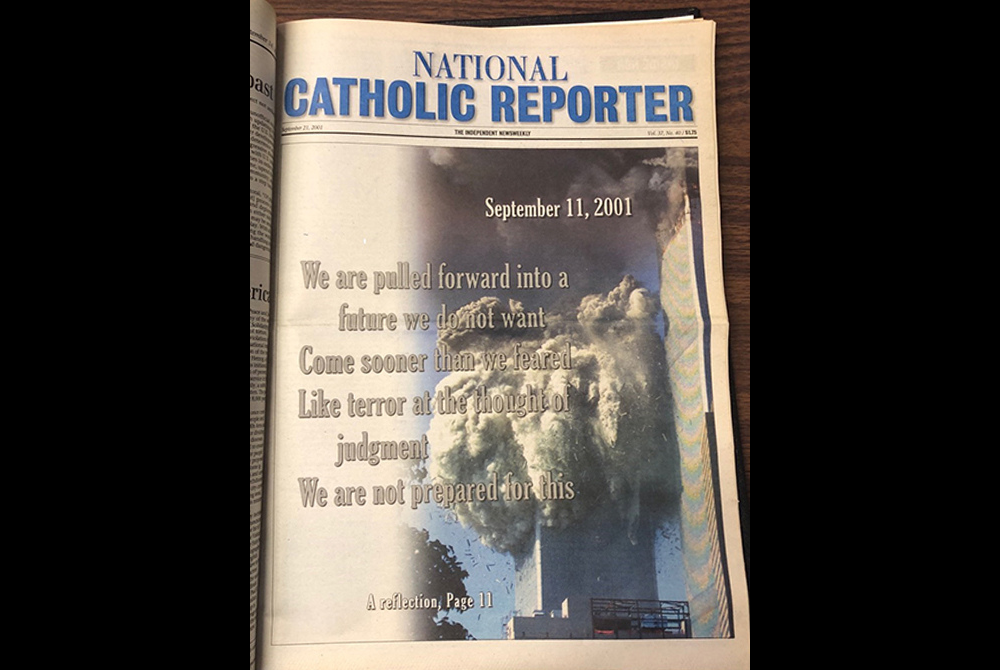

The cover to the Sept. 21, 2001, issue of the National Catholic Reporter (NCR photo/Jo Schierhoff)

Editor's note: To mark the anniversary of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, we asked Tom Roberts, who was NCR's editor at that time, to offer his memories of how the paper covered 9/11.

The front cover of The Washington Post Magazine for Sept. 5 displayed, against a red-washed background of the destroyed World Trade Center, a list of 25 areas of life — everything from TV and art to bigotry and immigration to journalism and love — that had changed as a result of 9/11.

Life-changing seems to be the theme in the tsunami of 20th anniversary reflections on the 9/11 attacks.

It's true — lots changed, especially for those of us in the United States.

Life became more precarious and uncertain. We had to face the reality that we were so hated by some in the world (How could they not like us?) that they were willing to die to make the point.

We became less secure; life became more inconvenient. Travel became long lines at the security checkpoints. Talk of vengeance was thick in the air. Not knowing who or what was behind this day became a seedbed for quick growing suspicions.

At NCR, we were alerted by an outside caller just before the start of a morning meeting to turn on CNN. By the time we did, the second plane had hit and it was clear that the first was not an accident and that we were witnessing an act of terrorism.

In that week's Inside NCR column, I wrote: "History has changed. We would never be the same."

That, too, was an easy assessment on the fly. Direct hits of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon with another plane downed in rural Pennsylvania were an unprecedented attack on the U.S. mainland. What next? How widespread? It was the language of reaction in the moment.

I joined so many that day in toggling back and forth between personal worry and concern about a national threat. Our daughter Rebecca lived in Manhattan about a 20-minute walk from the site of the attack. She was fine but for some time would have to show ID to get into her neighborhood. The other reality was that a handful of known hijackers had essentially shut down the country and left us all, we with the hundreds of billions of dollars in military might, staggered.

That's a harsh reality. With no place, really, to go, flight or fight, in the imagination, became an easy choice. Let's punish someone.

There are consequences, then and now, to working at NCR. They are the result of being devoted to unsparing questions and listening to and respecting voices in the far-flung corners of this sprawling Catholic community. Two things, neither flashy nor widely known, occurred that day within the confines of the NCR newsroom that to this day convince me that this little enterprise is something extraordinary both in terms of craft and purpose.

The first thing was an answer to a question that I posed to the staff because it was a Tuesday and we were well into a weekly cycle that ended with going to print on Thursday. The world was not yet at the point of calculating communications in nanoseconds. There still was some time to think. But all of the other processes, too, were slower, and there was no changing deadlines.

The staff without dissent voted, as I wrote back then, "to drop everything we had previously planned for that week's issue and concentrate solely on the events of the day. Our attempt is to dig deep into the heart and soul of NCR to help you think about the awful terror visited on us as a people. The full dimensions of these horrible acts will unravel only slowly. How to understand them will occur only with time. We hope that what you find in this issue will be a first step toward understanding."

Advertisement

The second thing was the response I received when I called reporters and columnists of all sort to ask if they would be able to dig into aspects of the story or comment on what they knew and turn around pieces in less than 24 hours.

None I asked refused or failed. I remember thinking to myself: "It's easy to think noble thoughts about nonviolent alternatives in those green times when all is calm and the question rests in cerebral quarters. But what about the dry times? What about the stuck-in-the-throat wail of bewilderment, fear, loss, even hatred of those who would do such evil?"

The community knew the answer, wrapped in a moving, original reflection on the moment by Pat Marrin, then-editor of Celebration.

By the midpoint of my own column I had begun to find my balance again, and that, too, was thanks to the extended community. If we had changed it was far more because we had been stripped of the illusion of privilege than it was some inexplicable act that had no foundation in a reality that we could understand.

We certainly could understand.

"As a country, now, we feel exposed and vulnerable," I wrote. "The faces of those who witnessed the tragedy, the sickness in the pit of my stomach — I have seen and felt it before, among villagers in the Guatemalan highlands and in those living on the side of a volcano in El Salvador, in Iraq's Baghdad and Basra. The utter disruption of daily routine, the search among normal people for normal words, the words we can call to mind to explain the inexplicable. On Sept. 11, we joined the rest of the human community in a way no one had ever wished. Now we share awful wounds and misery."

We shared the wounds, but we never commiserated, never stopped as a country to ask if immediate vengeance was necessary, or would be productive, or would convince people in the future to act differently.

President Joe Biden, who understands loss and himself opposed the ongoing war in Afghanistan, nonetheless, in exiting that war zone, continued to use the language of hopelessness and ignorant violence: "We will not forgive. We will not forget. We will hunt you down and make you pay," he said. Then, in an act of digital-age cowardice blasted away lives we are told were somewhat responsible for the loss of American life. The cycle is endless.

We might draw growing lists of how life has changed. We need more lists of how we haven't.

At some point during those early hours of trying to understand the attack and its consequences, the staff decided that the next issues of the paper would deal with big questions, the kind of questions that perhaps only a community of faith can dare to ask amid the fear of attack and the rise of nationalist sentiment.

The covers of those issues carried, in turn, explored the questions: "Who hates us, and why," "Patriotism" and "Was war the only choice?"

Questions, on this anniversary, that still beg for answers.