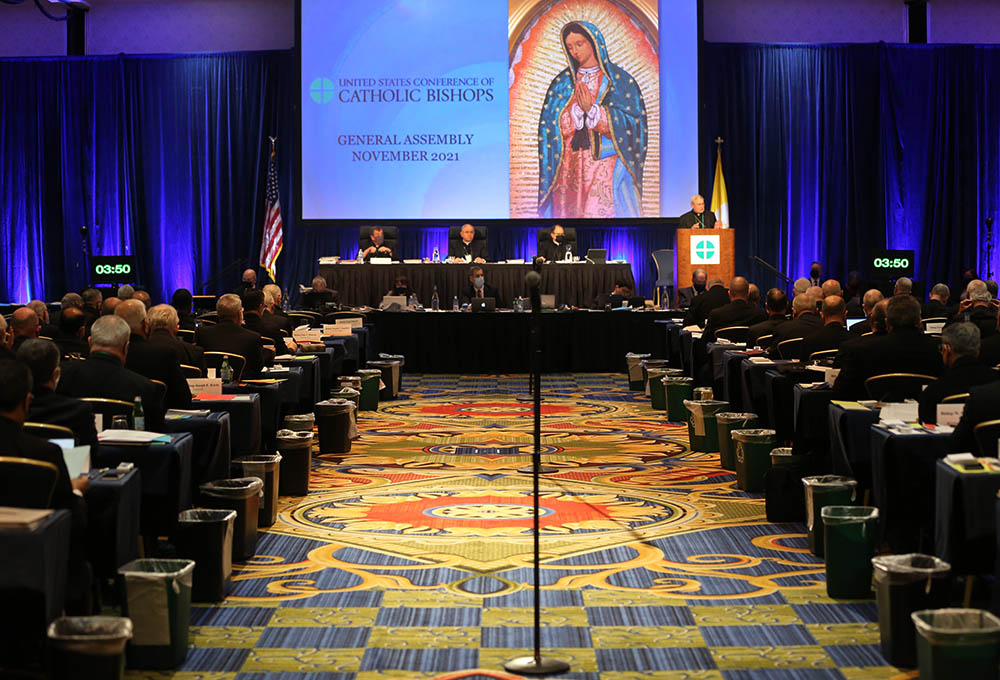

Bishops attend a Nov. 16 session of the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

The second day of the bishops' meeting in Baltimore, which finally included public sessions, continued the somewhat surprising quietude about which we were getting reports the day before. After months of anticipating fireworks over the effort to deny Communion to President Joe Biden, the Doctrine Committee seems to have devised a text that threads the needle between the divisions within the conference.

Even if you would likely flunk the text in any graduate-level liturgy seminar, politically it seems to be working. Unlike in June, when the culture warriors insisted the text explicitly bar pro-choice politicians from Communion, now they seem to have been defanged. The vote on the document is slated for late Wednesday morning.

One of the highlights of the day was the address by Archbishop Christophe Pierre, the apostolic nuncio. The nuncio is a diplomat; if you want a wartime consigliere, he is not your man. Still, when listing the challenges the bishops have seen during his five years in the U.S., he mentioned "polarization within the nation." Then, looking over at Archbishop José Gomez, the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and Archbishop Allen Vigneron, the vice president, he added, "and within the church."

When he quoted the celebrated ecclesiologist Yves Congar, he ad-libbed, "You remember Congar, yes?" I could not be sure if he was throwing shade, delivering an insult or not, but I am inclined to think so.

Pierre focused his speech around the theme of synodality and apostolic discernment. He recommended that synodal methods be applied to the bishops' pro-life strategy.

There are a number of pressing issues facing the church today. One is the pro-life issue. The church must be unapologetically pro-life. We cannot abandon our defense of innocent human life or the vulnerable person. Yet, a synodal approach to the question would be to understand better why people seek to end pregnancies, what are the root causes of choices against life and what are the factors that make those choices so complicated for some, and to begin to form a consensus with concrete strategies to build the culture of life and the civilization of love.

The initiative Walking With Moms in Need is actually a synodal approach. It seeks to walk with women, to better understand their situations, to work with pro-life and social service agencies to meet the concrete needs of expectant mothers and their children. Many expectant mothers are often suffering from loneliness, and common events, such as baby showers, are not part of their reality. Parishes, by listening to what some of the spiritual, social and emotional needs of the people are, can accompany women — even with small acts of kindness. Concrete gestures, not mere ideas, show forth the maternal, tender face of the church that is truly pro-life.

If the pastors of the church had spent the last 48 years since Roe v. Wade approaching pro-life issues in this synodal way, perhaps the cause would be further advanced.

Following a theme of Pope Francis' entire pontificate, Pierre said the church must accompany a wounded world. "The church, too, is wounded," Pierre said, citing the pandemic, the clergy sex abuse crisis and polarization. It is an interesting troika of afflictions. Only the pandemic was not a self-inflicted wound.

The nuncio noted that in the face of many challenges, some call for clear teaching, and clarity is needed to be sure. But, quoting Francis, he said: "A church that teaches must be firstly a church that listens."

The disconnect between the Vatican nuncio's address and the conference president's was stark.

In his presidential address, Gomez delivered a less irenic speech. I wonder if he realizes that when he starts by talking about the fact that our culture is increasingly secularized, he is not exactly wrong, but he is starting off on a divisive foot, noting a point of separation, not a point of commonality, focusing on what divides, not what unites.

If you start down that path, you almost always end up with a narrative that is either hectoring or patronizing or depressing. Gomez does not hector, but he tends to focus on the religious vision he posits that other people lack, never the way God might be already at work in people's lives.

It is true that we believe every human person is a mystery, and the answer to that mystery is Jesus Christ. But in our time and in our culture, the only people who will respond to a dialogue that begins with us disclosing we know we have the answer and our interlocutor lacks it, will be those who are desperate for, and satisfied by, an extraneous certainty.

Most importantly, such a dialogue almost always turns the faith into something more propositional than necessary.

The essence of the nuncio's talk, and the Holy Father's vision, is that a faith that is lived concretely, and that engages others by listening first, will do more to evangelize than a thousand propositions. That synodal vision is radically different from the approach outlined by Gomez. The disconnect between the nuncio's address and the president's was stark.

The elections for committee chair sometimes give a clear indication of the sense of the house. In 2017, the contest for chair of the Pro-Life Activities Committee pitted Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich, one of Francis' closest allies, against Kansas City, Kansas, Archbishop Joseph Naumann, one of the conference's leading culture-warrior bishops. Naumann, you might say, puts the "arch" back into archbishop.

As a sign of the importance the bishops attach to the work of that committee, it has always been led by a cardinal. But the bishops chose Naumann by a vote of 96 to 82. As I wrote at the time: "Not to put too fine a point on it, but this amounted to the bishops giving the middle finger to Pope Francis."

Seattle Archbishop Paul Etienne, wearing a protective mask, right, attends a Nov. 16 session of the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

This year, the election that most clearly illustrated the ideological divide was the election of a new conference treasurer. Archbishop Paul Etienne of Seattle is recognizably a Francis bishop. Bishop James Checchio of Metuchen, New Jersey, was the rector of the North American College in Rome from 2006 until 2016, and now serves on the board of the conservative National Catholic Bioethics Center and on Catholic University's Busch School of Business board of visitors. The former organization is a font of increasingly strident right-wing attitudes on bioethical issues, and the latter is an embarrassing incubator of libertarian economic ideas accompanied by puerile attempts to reconcile those ideas with orthodox Catholic social doctrine. The bishops selected Checchio by a margin of 135-106.

Other election results are more difficult to interpret. Personalities as well as ideological demeanor becloud attempts to interpret the results.

This year, the contest for the leadership of the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development evidenced this, with Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia facing off against Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois. Gudziak is likely not well-known to his brother bishops here in the U.S. because he spent most of the last decade in France, serving the Ukrainian Catholic community there. Paprocki is a first-class culture warrior and longtime nemesis of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. The Catholic Campaign for Human Development reports to this committee chair.

Gudziak won with 128 votes to Paprocki's 116. The bishops may not have known Gudziak, but they knew Paprocki, and while they may not be on board the Francis agenda, they did not want a complete culture warrior in charge of domestic policy for three years. The vote was a small mercy.

Advertisement

St. Louis Archbishop Mitch Rozanski was a Pope Francis bishop before there was a pope named Francis. A parish priest, he was catapulted into the hierarchy by Cardinal William Keeler, having never worked in the chancery. Bishop Steven Lopes of the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, the canonical organization established for those former Anglicans who converted to Catholicism but wanted to maintain their different liturgical forms. Why he was nominated to lead the committee on liturgy I will never know, but Lopes narrowly won, 121-120.

The other contests did not really disclose much about the direction of the conference. The real loser here was Archbishop Timothy Broglio, chair of the Committee on Priorities and Plans. That is the committee that recruits candidates for these elections. Broglio found some of the strangest, and simply bad, nominees I have seen in all my years covering bishops' conference meetings.

Outside the hotel, several hundred people, not the thousands advertised, gathered for the Church Militant rally. The rally was held inside an event venue, a giant tent, next to the hotel where the bishops' meeting was taking place and bordered on the opposite side by Baltimore's photogenic harbor.

At 11 a.m., when the rally was supposed to start, only about a third of the seats under the tent were taken. Someone carried large posters of St. Michael the Archangel. Another held a sign with a deliciously Freudian misspelling: "Follow Cannon 915!" The program of speakers was timed to coincide with the opening public session of the bishops' conference, so I did not stay for the speeches.

The day finished with a press conference that was, frankly, shocking. When asked about the genesis of the document on the Eucharist, Archbishop Jose Gomez insisted that the document had not been prompted by the election of Joe Biden as president, and the consequent desire of some bishops to deny him Communion. This year of argument about Biden’s worthiness to receive Communion was not really about Biden at all. It was all part of the pastoral plan, driven by concern that many Catholics did not understand the significance of the Eucharist. Those of us in the press corps started looking at each other, not able to remember a time in which a bishop at a press conference had so brazenly dissembled the truth.

Today the bishops will finally vote on this document that was about eucharistic coherence and denying Communion to pro-choice politicians until it wasn’t about that. Now it is not clear what it is about. Most bishops I spoke with acknowledged that the theology that informs the document is lousy, but also that they plan to vote for its approval, just so they can put this whole sorry episode behind them. This is what it has come to: Acute mediocrity rules the day. A long line of conference leaders, from Cardinal James Gibbons to Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, are turning over in their graves.