(Unsplash/Jason Leung)

Being an open, visible part of the LGBTQ+ community in a Christian church is never an easy task, much less using that visibility to give voice to the dignity of LGBTQ+ people in the face of a Christian culture that would prefer to erase various identities.

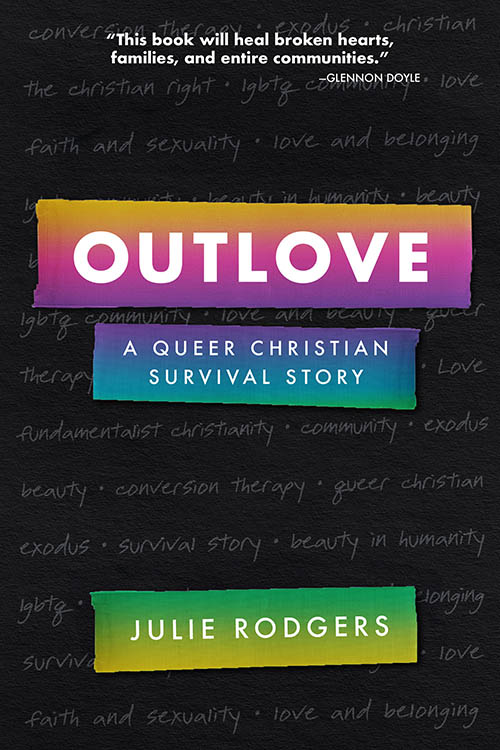

Outlove: A Queer Christian Survival Story is the biographical account of Julie Rodgers, who grew up fiercely evangelical and passionately in love with Jesus with one small problem: She was attracted to other women.

Her mother sent her to participate in a group called Living Hope Ministries, an "ex-gay" ministry. Rodgers traveled to conferences with Living Hope and told her story, eventually speaking at conferences for Exodus International, another ex-gay conversion organization. She believed for years that if she could just be good enough, God would make her straight.

Julie Rodgers, author of "Outlove" (julierodgers.com)

Freedom from this cycle of shame and disappointment took her years to find, but ultimately came when she discovered beauty and sanctity in her queer identity. She took this newfound belief to her next job as an out lesbian chaplain for Wheaton College, an evangelical university in Chicago, where she encountered a new dilemma: The college felt she was too gay, and many progressives felt she was too Christian.

Outlove is a hard book to read at times, especially for LGBTQ+ readers who have been in Rodgers' shoes. She writes vividly about the internal process of questioning her identity and how the pressures she felt played out in her relationship with her body: denying herself food and self-harming by heating up a quarter and using the hot metal to burn lines on her own shoulders. Her whole life was formed around the quest to not be gay.

Even later, when her struggle with mental health began to improve and she was able to stop self-harming, Rodgers continued working in Christian spaces where her queerness was the focal point for people around her.

There's a moment in the book when Rodgers is out in public and, for the first time, she's not engaged in any kind of work related to being gay: She's not speaking at an ex-gay event, or working on campus as a visible queer chaplain. It is then that she realizes her whole life is dominated by her queer identity, as if being queer is a glass ceiling, limiting how high she can ascend in an evangelical environment. She is always on display, always under scrutiny. Is she Christian enough? How can she support same-sex marriage? Why would she choose to call herself gay?

Rodgers' experience will be familiar to LGBTQ+ Catholics trying to work in Catholic spaces.

For me, the experience of alienation took different forms, like when people inquired if I had a significant other or when I was planning on getting married. People would give very specific compliments about my work or creativity, but avoid giving compliments about my appearance or masculine style.

Advertisement

Although I never spoke about my identity publicly, it felt like an open secret, with everyone a voyeur to a part of me but no one allowed to address it directly. It was impossible to talk about the unique struggles that I faced as an LGBTQ+ person. I, too, felt like I was under a spotlight I could never escape, always visibly different than everyone else, always scrutinized more.

Ultimately, Outlove is not a book about theology. It is not an argument in favor of same-sex marriage. It's not even about whether or not gay Christians should be celibate. Outlove is about Rodgers' growing understanding that theology doesn't matter to someone who doesn't want queer people to be a part of the church. It doesn't matter what words are used to describe their identity or how "perfect" they act. There are simply Christians who are so uncomfortable with the existence of queer identities that they will refuse every effort to help queer people feel at peace and at home in the church.

One of the biggest takeaways from the book is that the reality of who you are — on every level and in every way — is important and powerful. To obsessively focus on sin, or to call queer identities themselves sinful, is deeply harmful to queer people. Feeling free to be yourself and pursue your relationship with God without judgment, scrutiny or shame is important.

Baptism makes us Catholic, and being gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer does not take that away. There will always be Christians and Catholics who don't accept queer people, but queer people truly have so much to contribute to the church, if only they can be allowed to share.