Rosemary Radford Ruether in 1974 (NCR file photo)

Tributes and condolences light up the Internet as word of the peaceful passing of feminist theologian Rosemary Radford Ruether, who died on May 21 at age 85, makes its way around the globe.

Rosemary, as most people called her, was an internationally renowned Catholic scholar activist who leaves scores of books, countless articles, more than a dozen honorary degrees, and academic distinctions of every kind. Her contributions to feminist scholarship, Catholic theology, Palestinian rights, ecology, anti-racism, peace work and so much more will be the subject of dissertations for generations to come.

She served on various boards, notably Catholics for Choice, and on editorial groups and committees too numerous to catalog. Yet her legacy lies not only in the heads, but also in the hearts of family, friends and students who mourn her while we count our lucky stars to have been in her orbit.

Many people have great 'Rosemary stories,' not simply of the incredible scholar, teacher and activist, but more so of the sometimes shy but always kind, humorous person with an open mind and even more open heart.

Rosemary Radford Ruether in 2009 (Annie Wells)

My stories go back to the early 1970s at Harvard Divinity School, where Rosemary spent a year as a visiting professor. She would speak of those times saying, "You remember, Mary, when we were at HDS ..." Of course, it never occurred to her to mention that I was a first-year graduate student, all of 21, and she was auditioning for a chair that she proved too progressive, not to say too feminist, to hold.

Her collegial approach, encouraging other people and lifting as she climbed, taught her students to do the same. We saw up close what it took — endless hours in the library, syllabi an inch thick as she worked out a whole new schema for studying women left out of the history of religion; courageous intellectual forays; an ability to change one's mind with integrity; writing that included the best scholarship and the funniest parody; and a courteous, rapid response to every shred of correspondence long before email.

I still marvel at how she did it all and maintained what is now called life-work balance. Being a woman in a man's world of religion and scholarship was beyond hard.

When the Harvard Divinity School residence Rockefeller Hall was dedicated in 1972, hungry students sat in our dorm rooms smelling the delicious meal being served to donors and dignitaries below. Rosemary was present at the dinner, where one Rockefeller son extolled the extensive virtues of his great father.

Rosemary was reported to have uttered in a stage whisper, "Didn't that man have a mother?" Her brilliant sense of humor leavened more than one hard situation.

Rosie, as we sometimes called her, was a phenom. I hosted her once in Berkeley, California, in the 1970s, when she was invited to be on a doctoral committee at the Graduate Theological Union. She read the academic materials in a flash. Then she closeted herself in the study to write her comments in preparation for the defense.

All I could hear from the living room was the loud clanging of my electric typewriter being put through its paces. I feared the machine might catch fire because she was typing so fast. Rosemary emerged shortly with several single-spaced pages of erudite comments.

Advertisement

Her appreciative and critical reading on an obscure topic that only she could handle enhanced the defense. The student passed, and thus Rosemary launched one more colleague by partnering rather than obstructing, collaborating rather than gatekeeping. She showed the rest of us how feminist work is done.

We were in Jerusalem for a conference on liberation theology with Palestinians in 1990. Some high-ranking local clergy, including some patriarchs and those addressed as "Your Beatitude," invited our international group to a lovely reception in a mirrored room. One church leader of more than ample girth, robed in a black cassock with a brightly colored cummerbund, delivered himself of an oration: "Jesus, the divine embryo, who from before the beginning of his life ..."

Our members eyed one another in the mirrors while this well-meaning gentleman rocked on the edge of a platform working himself into a theological lather. We had all we could do to stifle giggles and retain some semblance of composure lest we commit an international ecumenical faux pas. Rosemary was beyond amused with the rest of us. It was better that the gentleman did not know to whom he was addressing his remarks.

Rosemary Radford Ruether in 1990 (Mev Puleo)

Rosemary's generosity to students is the stuff of legend. Many students mention her empathy as their different learning needs and styles emerged. She could pivot intellectually and was nimble in her methods to accommodate various ways of learning.

One of her brightest graduate students suffered a deep depression and tried to take her own life. The student confided that Rosemary took her into her home and rocked her like a baby as she recovered. My generation learned from Rosemary that our work is not simply intellectual, but also personal and pastoral.

Other former students tell of living for stints with Rosemary, her husband and their three children in their home in Evanston, Illinois, during Rosemary's long tenure at Garrett Evangelical Theological Seminary and Northwestern University. Their hospitality, especially for international students, made the difference that allowed many to finish their studies and to do so with a sense of community in a unique American household.

Her husband, Herman Ruether, a political scientist by profession, is one of the few men of his generation who was smart and secure enough to love and share daily life with a phenomenal woman. He handled more of the home responsibilities than most men of his time. He encouraged Rosemary in her work, shared her interests with enthusiasm, and engaged in joint projects especially on the Middle East. Their children were at the center of their lives.

Rosemary was a world-class theologian. She was one of the first feminists to travel extensively to lecture and learn, introducing concepts and strategies that helped other women find their own voices, histories and trajectories. She went where she was invited and needed all over the globe. She listened, and she enjoyed it. If a group wanted to study, she was there to teach. In each place, she learned about the local reality — the women's groups, ecological efforts and other liberation projects.

When she got home, she wrote about them in an effort to build networks and create global strength. She was well aware of the dangers of white American hegemony, always balancing that with ways to empower women who were finding their way. Scholarship for solidarity was Rosemary's brand, whether on ecology, Palestine, or Catholic women's ordination.

Rosemary Radford Ruether in conversation in 1974 (NCR file photo)

She taught the rest of us how to travel lightly on our theological excursions. She rivaled Maryknoll Sisters who are famous for their smart simplicity. When a host picked her up at the airport there was virtually never a stop at the baggage claim. She carried what she needed, often just a briefcase even for a few days.

I escorted her to her airport shuttle as she left a meeting that WATER hosted about how to counter the Vatican's active oppression of nuns. She had a small, light backpack on wheels so I offered to carry her suitcase. Silly me, there wasn't one, even for a four-day cross-country trip. There was not a "diva" bone in her body. It was another style lesson for those who followed her.

Rosemary was a complete theologian, a "scholar activist," as I have written about her. She was a painter (she considered an art major in college) who liked to garden and cook. She felt very at home at Grailville, the women's farm and conference center in Loveland, Ohio, long the headquarters of the U.S. Grail. She and her late Grail friend Janet Kalven (on whose birthday Rosemary died) would talk about herbs and enjoy the fruits of the garden. I once stayed in the turret room in Grailville's Main House where Rosemary wrote some of her most influential work. I hoped a little of her talent might rub off on me.

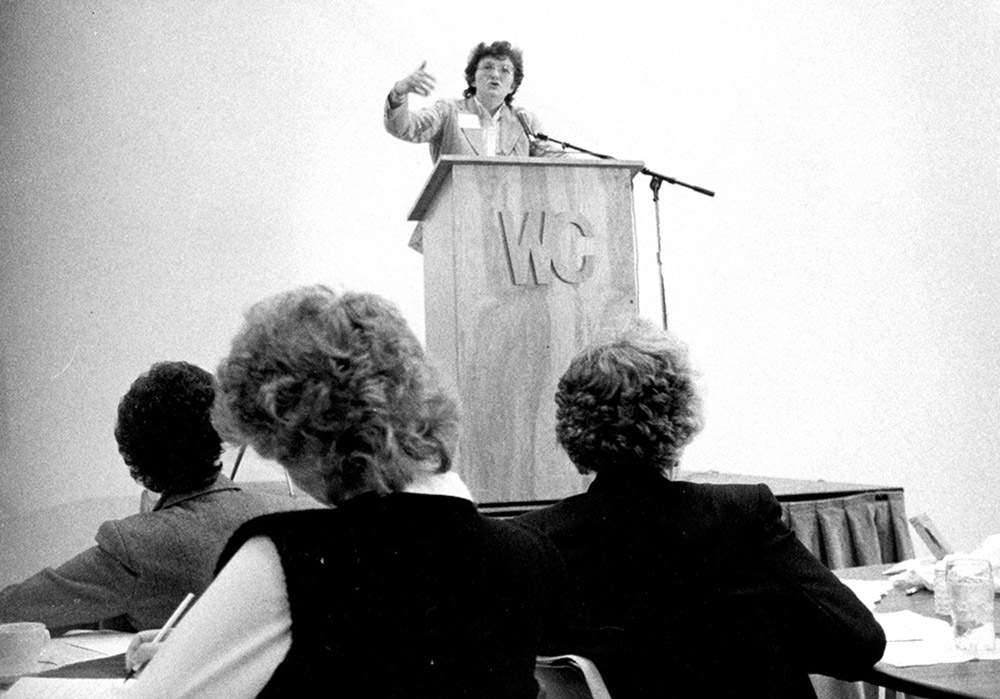

Rosemary Radford Ruether gives an address in 1984. (NCR photo/Charlene Scott Warnker)

Rosemary loved her garden at Pilgrim Place, the progressive retirement community in Claremont, California, where she and Herman retired. When I was visiting, she arrived at a meeting about ecumenical global volunteer opportunities toting her lunch on a simple plate. She told me she had made it herself. By that she meant she had baked the bread, grown the basil, and harvested her own tomato. Ok, and probably written an article that morning.

An Irish friend recalls that Rosemary arrived in Dublin once and asked about a washing machine. She had traveled in her gardening dress straight from the "new sod," too busy to change and still catch her flight.

Women-church played a large part in Rosemary's theology and spirituality. She and feminist biblical scholar Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza laid the groundwork for forms of feminist Christian faith that replace kyriarchal structures with egalitarian base communities, shared decision-making, and mutual ministry. Everything from architecture to exegesis, from finances to music can and must reflect the values of equality and justice if feminists are to participate.

Many feminists left Christianity, especially Catholicism, when it proved resistant to change and unhealthy for many people's spirituality. But for those who decided to struggle with and radically reshape the contours of patriarchal Christianity, Rosemary's and Elisabeth's work provided a useful foundation.

Rosemary Radford Ruether, right, with Joan Harriman, co-founder of Catholics for a Free Choice, in 1982 (NCR photo/John Ficara)

Rosemary belonged to a local women-church group in Claremont. She was also supportive of the Mary Magdalene Apostle Catholic Community in San Diego, led by Roman Catholic Women Priests. She encouraged an inclusive approach that honors the varied ways Catholic women live out their vocations. I agree with her.

Ironically, I would guess that many people in both communities worshipped alongside Rosemary without knowing much about her shaping influence on the women-church movement. She would never have mentioned it, but history will not forget.

Her sisterly affection was quiet and powerful, a word here, a gesture there, always present, never showy. Diann Neu, my partner, recounted being at a bucolic conference center with Rosemary when Diann got word that her father had died. After I consoled her, Diann went outside to spend some time in nature reflecting on her loss. The next thing she knew, Rosemary was beside her, a strong, supportive but unobtrusive presence, offering sympathy and care.

Rosemary and I were paired once in a feminist liturgy for a brief moment of sharing. The instruction was to use a song lyric if we could to convey a wish for the partner. I was not surprised that Rosemary, who taught for a decade at Howard University Divinity School, chose a spiritual that she probably learned in her civil rights activism. She said, "Oh, Mary, don't you weep, don't you mourn."

I won't weep over your passing, Rosemary. Instead, with deepest gratitude for your example, I will work as you did to end the many reasons for weeping in our world. Rest in peace, Rosemary, and rise in justice.