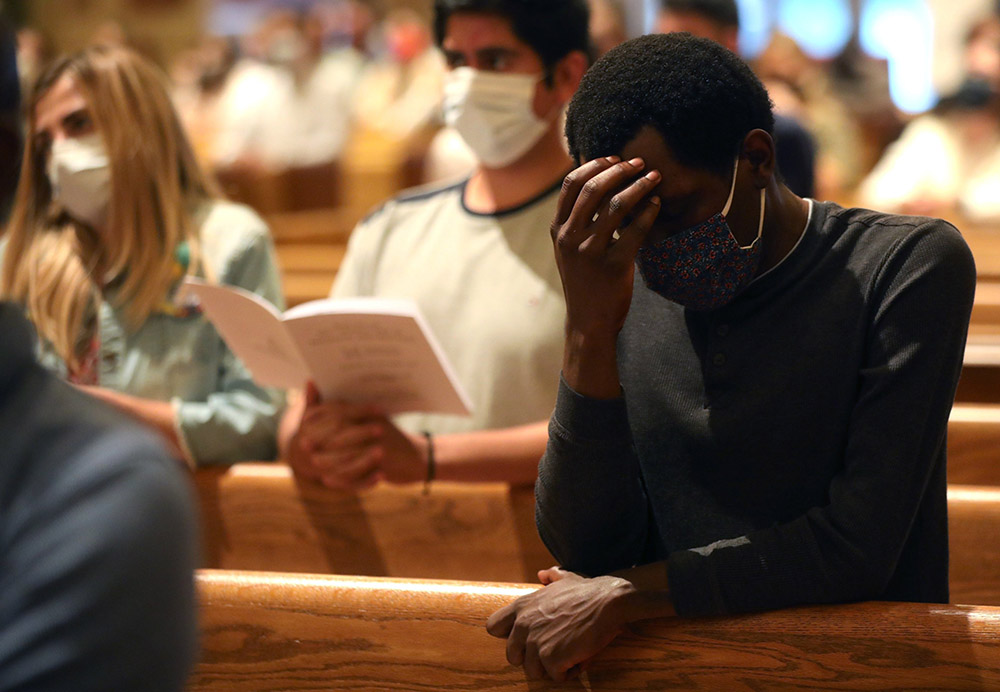

People attend Mass in the Crypt Church at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington Sept. 16. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

For North American Catholics, Fratelli Tutti's release last October appeared to be overshadowed by the drama before and after the U.S. election. The pope's solemn reading of the "signs of the times" expressed by his concern for the "shattered dreams" due to "reductive anthropological visions" that degrade, deprive and divide struggled to find a foothold among people consumed by rising tensions and intensifying political partisanship.

This encyclical rebukes the polarization and partyism that infects not just our country but also the church, condemning the culture wars fomenting "us-versus-them" mentalities. A year later, it's clear these are lessons some U.S. Catholics still need to learn.

In Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis not only confronts widespread distrust and division, he also laments that "we are more alone than ever," and directs our concern to those subject to discrimination, exclusion and violence. He takes note of the vulnerability of women and the scourge of racism in many social contexts, but never acknowledges the way the church perpetuates marginalization and inequality among its own members.

The encyclical's reliance on the gendered term "fraternity" and reliance on exclusively male sources and examples jeopardize the credibility of the document to model the kind of solidarity of "a people with a future" who are "constantly open to a new synthesis through its ability to welcome differences."

The pope encourages us to recognize social problems as spiritual problems, which raises the question of how the church will address its inadequate approaches to religious and moral formation that contribute to these spiritual problems.

The pandemic both caused and revealed that many people have stopped going to church and many people have stopped seeing themselves as church.

The disruption and death caused by the COVID-19 pandemic irrevocably impact both the composition and reception of Fratelli Tutti. Around the globe, people are carrying a great deal of pain and grief from the human toll we have endured over the last 19 months. Beyond the individual, social and economic fallout, there is also the practical matter that fewer and fewer Catholics are participating in parish life.

While a good number of people may be faithfully tuning in to livestream liturgies or attending in person in order to receive Eucharist, a sizable fraction of the body of Christ have long felt cut off from the community.

This is true for those who find livestream Masses an untenable approximation for "fully conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations"; those who feel unsafe to attend church in person due to risks of exposure to the coronavirus; and those who have been made to feel invisible and insignificant by the church, as is the case among many women, LGBTQ persons, Black and Latinx Catholics, those who have divorced and remarried, widows and others whom the church too rarely welcomes and prioritizes with attentive pastoral care.

For decades, many North American Catholics have viewed the parish more as places where sacraments get dispensed than as the center of community life. In a consumer society, this tends to train Catholics to view parish staff as "service providers" and parishioners as "service recipients."

People arrive for Mass at San Jose Catholic Church in Austin, Texas, Sept. 5. (CNS/Bob Roller)

If laity don't like the music, homilies or religious education at one parish, they may "church shop" until they find a more satisfying customer experience, perhaps even relying on online reviews of churches that risk comparing places of worship to restaurants or retail stores.

This only reinforces the view of church as a place to go, rather than a people called into community united by a mission to follow and emulate Jesus Christ. The pandemic both caused and revealed that many people have stopped going to church and many people have stopped seeing themselves as church.

There are many reasons for this, of course. Some of it has to do with the marginalization of women, the mistreatment of LGBTQ persons, complicity with white supremacy, and examples of judgmentalism, hypocrisy and corruption in a counterwitness of Jesus' teaching and healing ministry oriented toward inclusion and mercy.

Some of it has to do with exhaustion and frustration with bishops' tunnel vision on some issues (namely, abortion) and lack of urgency around other social issues, whether that may be systemic racism, anti-democratic legislation that restricts voting rights or climate crises exacerbated by fossil fuels.

A lot of it has to do with the moral catastrophe of clergy sexual abuse and its cover-up. Two years ago, a Gallup poll found less than a third of Catholics believe priests are honest and ethical. Discrediting, shaming and silencing survivors of clergy abuse compounds spiritual malpractice by the church and robs the faithful of the truth of what has happened in our communities.

Where do we turn when the field hospital is causing — not curing — wounds?

Even after it has come to light that thousands of priests abused more than 100,000 people, the church is making feeble progress toward truth-telling, contrition and restorative justice.

A church that excludes some members from the Communion table, that relies on obligation or guilt to compel participation, that protects perpetrators of spiritual and sexual abuse, and that constructs roadblocks that hinder transparency, accountability and prevention has little moral authority to condemn harmful cultural anthropologies.

The church is facing a crisis of safety and trust. No steps toward solidarity can be taken without reckoning with the pain and anger, grief and betrayal caused by the church. Solidarity will remain a hollow slogan unless and until there is a drastic change in how power is exercised in the church, correcting asymmetries that deny power to some and consolidate it through structures that reinforce hierarchicalism and clericalism.

When Francis introduced himself to the world eight years ago, he presented a vision of the church that should be more like a field hospital than a fortress. While this gives us a compelling image for carrying out the triage that's necessary to tend to the wounded, it does not fit the scale of the problems the church faces.

A field hospital provides urgent care but it cannot redress harm or prevent wounds. Like Fratelli Tutti, it also sends the message that problems exist in the world but not the church itself. Where do we turn when the field hospital is causing — not curing — wounds?

Advertisement

Francis' vision for solidarity finds inspiration in the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37). The pope exhorts us to adopt his willingness to go into the ditch, taking up the vantage point of the one in need, and doing what we can to "rebuild our wounded world," since "any other decision would make us either one of the robbers or one of those who walked by without showing compassion. ... We cannot be indifferent to suffering; we cannot allow anyone to go through life as an outcast."

Instead of catering to personal tastes, comfort and convenience — as our consumer society insists should be the norm — we are challenged to "humbly regard others as more important than ourselves, each looking out not for [one's] own interests, but everyone for those of others" (Philippians 2:3-4).

This is the costliness of loving God by loving our neighbor, of embracing our vocation as being "made for love," a love meant to forge kinship that is "open to all" and "excludes no one."

Fratelli Tutti underscores that love is social and political. The fifth chapter is dedicated to how love can inspire a "better kind of politics" in order to bring people together across differences. No doubt the political landscape would surely benefit from a more robust commitment to practice virtues like humility, curiosity and compassion through honest dialogue and a shared commitment to the global common good.

People in Washington pray during a World Day for Migrants and Refugees Mass at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle Sept. 26. (CNS/Catholic Standard/Andrew Biraj)

But mutual respect, equality and reciprocal concern are needed in every arena, and especially in our wounded church today. Formation happens in our relationships and the practices we share; we are what we repeatedly do together.

If the local church can be more than places where sacraments get dispensed, they will have to be home to life-giving rituals that facilitate inclusive encounters, foster safety and trust, practice authentic and vulnerable dialogue, provide both support and accountability, and initiate collaboration to defend human dignity and rights in the pursuit of peace and justice for all. People will have to be invited to shift from spectators to stakeholders. Solidarity is only possible when everyone consents to putting some skin in the game.

This latest encyclical provides a soaring vision of catholicity by celebrating — not just tolerating — unity in diversity. Francis' call to "dream together" of an ever more inclusive and interdependent communion offers an illuminating and encouraging resource in the face of so much social fragility and fracture.

Appealing to our dreams is an invitation to contemplate who we want to be on the other side of the pandemic, so we don't settle for the church or world as they are. Dreams allow us to tap into our deepest desires. In Scripture, dreams reveal what God wants for and from us. At their best, dreams can stretch what we imagine possible so we don't become complacent with an unjust status quo. At their worst, they stir up pain or play on fear.

In either case, eventually, we have to wake from our dreams. A year after the release of Fratelli Tutti, we have to take up the work of moving from dreaming to doing so that these prophetic words find expression through shared rituals that widen hospitality, animate honest dialogue, and activate robust co-responsibility in delivering hope and healing to our church and society.