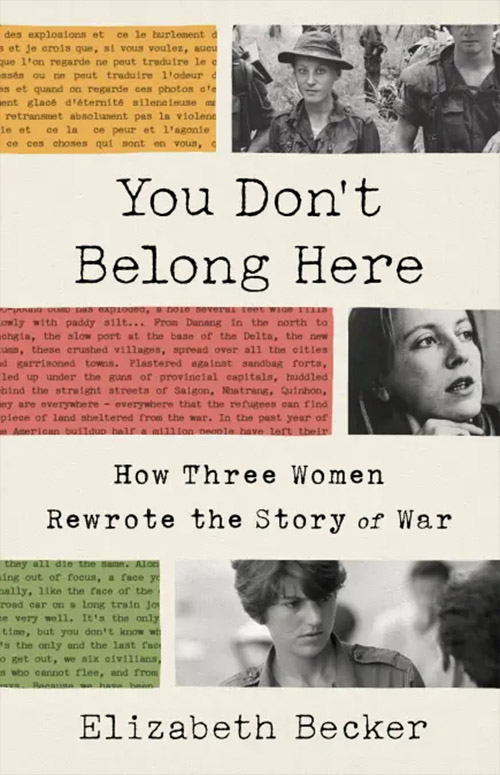

In a photo taken by French photojournalist Catherine Leroy, U.S. Marines get ready for a final assault on a hilltop in northwestern Vietnam on May 3, 1967. (AP/Catherine Leroy)

The tragic images from Kabul last summer spoke of waste, dashed hopes and human cost. When it was all done, after more than 170,000 lives were lost and $1 trillion had been spent, the Afghan tragedy shared similar echoes with the Vietnam War.

The earlier war was, in retrospect, a wholly unnecessary conflict that, had it not happened, would have spared 3 million-plus lives, most of them Vietnamese. And, of course, it probably would have had the same result — a unified country under Communist Party rule with a capitalist economy that enjoys decent relations with the United States.

But the war did happen, and Elizabeth Becker's You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War doesn't spare the reader the awful details of what the conflict exacted in human lives.

Elizabeth Becker, author of "You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War" (Courtesy of PublicAffairs)

But Becker has another story to tell: an accomplished and deeply reported account of three female journalists who were pioneers at a time when war reporting was very much a male domain. Women still had to fight male editors and colleagues to get the chance to cover what Becker rightly calls the most important geopolitical event of the 1960s and 1970s.

The book is prefaced by a knowing quote from one of the legendary male reporters in Vietnam, the Pulitzer Prize winner Peter Arnett, who observed, "The Vietnam press corps was a male bastion that women entered only at the risk of being humiliated and patronized. The prevailing view was that the war was being fought by men against men and women had no place there."

Becker's focus on three journalists — American writer Frances FitzGerald, French photographer Catherine Leroy and Australian reporter Kate Webb — is wise, because it establishes a condensed and readable narrative. But that focus doesn't slight other female pioneers who are also cited. These include the Americans Martha Gellhorn, whose Vietnam reporting was grounded in her earlier experiences covering World War II, and Gloria Emerson, who covered the war for The New York Times.

Choosing FitzGerald, Leroy and Webb also gives the book a geopolitical balance: Forgotten by many is that Americans were not the only outsiders fighting in Vietnam — Australians had a large force — and that the American-led war was essentially the continuation of a conflict that the French lost in the 1950s. That was a deep blow: Becker poignantly recounts how Leroy's father, an engineer, broke down upon hearing the news that the Vietnamese had defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

The three women had distinct careers and approaches to covering the war — their work didn't overlap. Perhaps the most vivid contrast is the lives of FitzGerald and Leroy. FitzGerald arrived in Vietnam as a well-connected East Coast product of Radcliffe College whose eventual best-selling Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam was an instant classic.

Leroy, by contrast, was a middle-class French woman who fell into photography after years of drifting, and scraped by to get a footing in the fiercely competitive, and very male-dominated, field of war photography.

Not surprisingly, Leroy — who probably enjoys the most vividly drawn portrait in the book — sought and craved respect, Becker writes, but instead found herself ostracized and dismissed by male colleagues. FitzGerald and Webb also keenly, and painfully, shared similar experiences.

Advertisement

"The reasons given were couched in personal terms," Becker writes of the French photographer. "Leroy was pushy, ambitious, shoving to get on a helicopter to the battlefield or back to Saigon with her film. She had no manners. In the field, she could be a hothead. When she didn't get her way, she would flare up, sometimes using profanity. She swore."

That might seem like part of the job description for a war photographer. But as Becker notes, it made no difference "that male reporters and photographers also swore, also threw their weight around to get what they wanted, and were also ambitious."

"Leroy was expected to be lady-like. She was an interloper who had become an affront to the profession." Becker's justified conclusion: "It came down to her gender: she didn't belong because she wasn't a guy."

Fortunately, Leroy eventually gained the respect of her peers — though Vietnam continued to haunt her personally in her post-war life. (As it did Webb; both women had clearly been traumatized by their experiences.) Only FitzGerald, now 81 and the only one of the three women still alive, continued on a steady path, penning other acclaimed books on American themes and historical subjects.

But Becker notes that even a respected figure like FitzGerald — who had the advantages of family money and, due to her upbringing, was "neither easily intimidated nor fooled" — also faced challenges.

Cover of "Fire in the Lake" by Frances FitzGerald (Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

Fire in the Lake — a book I remember as essential reading for anyone studying the war in college, as I did, in the late 1970s — was bafflingly left off a suggested reading for Ken Burns' PBS 2017 documentary on the war. Why? Apparently because later scholarship has eclipsed some of Fitzgerald's earlier research and conclusions.

But could sexism have also been a factor? I can't be sure, but reading between the lines, I'd say it is possible. Becker quotes historian Fredrik Logevall as saying some of the criticisms of Fire in the Lake — easily the most honored book about the war — may be due to simple envy.

"Whatever we want to call it — a first-cut history — this book stands up very well even though she [Fitzgerald] didn't have access to archives," Logevall told Becker. "I would put it on a short shelf of really important books on the war. It's of enduring importance."

A few minor criticisms of You Don't Belong Here are inevitable. There are some small but still unfortunate copy-editing lapses: a few place names and proper names are misspelled. Small points, true, but still noticeable.

And while Becker's first-person account of her own reporting experiences in Southeast Asia provide a welcome and moving introduction, a reappearance at the end of the book seemed a bit jarring, given the successful, even riveting, third-person reporting of the three women subjects. (Becker's recollections are vivid, and would be welcome in a separate book, perhaps a memoir.)

Becker recounts working with Webb as the neighboring war in Cambodia horrifically continued after the 1975 victory of the Vietnamese communists. Becker, who was active in feminist circles in the United States, said Webb "considered women with my views part of the problem, not the solution." Leroy was also prickly on the subject of women's liberation, Becker notes.

That may seem contradictory, but it is part of the vivid, humane and engaging portraits in You Don't Belong Here that bring three female trailblazers to life. Becker recounts both personal and professional accomplishments and setbacks alike, and that is a real success of Becker's valuable narrative. This reader grew to care about the women as individuals.

Did FitzGerald, Leroy and Webb rewrite "the story of war"? Perhaps that's a bit grand, but they certainly gave voice to the war's victims, both civilians and soldiers. (That's a tradition that continues today in fine reporting from Ukraine, much of it done by women.) FitzGerald's reporting and research, in particular, were keen in providing American readers with a much-needed Vietnamese perspective.

And the three women certainly began to rewrite the narrative that war reporting is solely a male domain. For that, those of us who grew up in the war's shadow and later became journalists owe them a deep debt of gratitude.