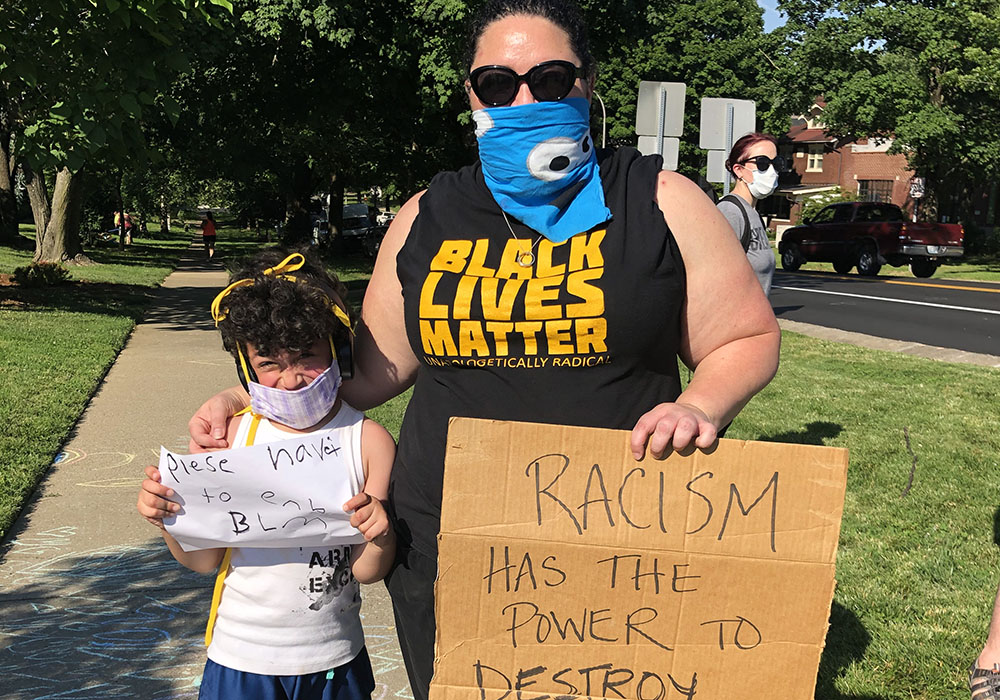

Anice Chenault, a parishioner of St. William Catholic Church in Louisville, and son Justice participate at a family-friendly protest organized by Mama's Hip, a parenting co-op, and Louisville Showing up for Racial Justice. Justice's sign says "Plese (Police) have to End. BLM"; Chenault's says "Racism has the power to destroy us all." (Photo provided by Anice Chenault)

The police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd that sparked massive actions across the U.S. this summer "felt personal" to Louisville, Kentucky, organizer and St. William parishioner Anice Chenault.

Anice is white and Arab, married to a Black man, and has a mixed-race son. She said the killings exacerbated the feeling she has every morning that when her husband, and any other person of color, gets up, they take their life into their own hands.

In late May, Chenault joined the Louisville Showing up for Racial Justice (SURJ) chapter's actions. The group's ongoing "Freedom Friday" car caravan to release people in jail and detention facilities at risk of COVID-19, transformed into a call for police accountability and justice for 26-year-old Taylor, a Black woman killed by police in her Louisville home.

Chenault said parishioners from St. William's made up about a fourth of the people in the caravan, who rode alongside Black Lives Matter community leaders. Chenault described the parish as "one of the few remaining true Vatican II parishes." The approximately 200 parishioners, who are largely older and white, are active in many justice ministries, and were ready to stand with their community.

Parishioners from St. William Catholic Church in Louisville joined members from the Louisville Showing Up for Racial Justice chapter along with Black Lives Matter community leaders to advocate for police accountability in the wake of Louisville resident Breonna Taylor’s murder. (Sonja de Vries)

Across the country, Catholics have responded to the moral call to stand against police brutality experienced by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous or people of color) by showing up, educating themselves and engaging in deep conversations about white supremacy.

On the day of Floyd's funeral, Holy Family Catholic Church in South Pasadena, California, rang its bells for eight minutes and 46 seconds — the amount of time white police officer Derek Chauvin had his knee on Floyd's neck while Floyd, a Black man, pleaded that he couldn't breathe, later dying in police custody.

Though the parish had been active in immigrant justice in the past, Parish Life Director Cambria Tortorelli said that the actions taken this spring by the parish were the first specifically against anti-Black racism.

Holy Family is home to about 5,000 families and Tortorelli describes it as a "big tent" Catholic community, with families across the political spectrum and largely white. This spring, the parish launched its first ever anti-racism programming, a four-part online series, designed by the Inward Bound Center for Nonprofit Leadership called "Racism in America: What is Mine to Do?"

The parish also offered a mass for racial healing. This approach to anti-racism work, Tortelli said, was important for her parishioners who want to be engaged, though may be less likely to attend a public action.

Parishioners from St. Williams Catholic Church in Louisville joined members from the Louisville Showing Up for Racial Justice chapter along with Black Lives Matter community leaders to advocate for police accountability in the wake of Louisville resident Breonna Taylor’s murder. (Sonja de Vries)

"There are very few places that people can go and express themselves," Tortelli said. "One of the most important things is that the Catholic Church shouldn't be afraid to put their arms around this issue [racism] and get into the fray, done through the lens of the Gospel of Jesus Christ."

In Chicago, Old St Patrick's Catholic Church, home to 8,600 mostly white families, has a rich history of justice advocacy. Currently, the parish is focusing its racial equity energy on educational initiatives and on participating in "peace circles" with St. Agatha Catholic Church, a predominantly Black parish.

Kayla Jackson, social justice ministry coordinator at Old St Pat's said that between 25-40 people from her parish and St. Agatha's have been meeting once per month for the past four years with other members of the North Lawndale neighborhood, where St. Agatha's is located.

"We get together, share a meal, have a short educational piece," Jackson said.

After the presentation, which often has an intersection of race, participants break into small groups to unpack and share knowledge, using the peace-circle format. There is time at the end of each meeting for calls to action to support one another's justice initiatives.

"I think it's allowing people to build the muscle to have the conversations and hopefully bring it to other places of their lives," Jackson said.

Additionally, Old St Pat's is offering online anti-racism modules through JustFaith Ministries. Jackson said the program is popular, and she quickly filled three cohorts of 15 people each.

Chicago parishioners from Old St Patrick's Catholic Church and St. Agatha Catholic Church have been meeting once a month for the past four years in "peace circles," to cultivate community and discuss racial justice. Parishioners are pictured in a 2017 photo. (Kaitlynn Scannell)

The Society of Jesus West Province has been working to address racial inequality including anti-Black racism for the past six months through a discernment process with 270 people across 12 cities in the province. This fall, the province will launch Jesuits West Collaborative Organizing for Racial Equity, or CORE.

CORE will focus on three initiatives: helping white people understand their whiteness and helping people of color feel connected, work for institutional change around race, and ways Jesuit institutions can advocate for public policy through a race-equity lens.

"What we are doing is really trying to lift up and champion the work already happening in our ministries," said Annie Fox, provincial assistant for social ministry organizing. "A lot of people in parishes said, 'We want to do this work and we think we can do it better together.' "

This summer the province is also offering a four-part course titled "Wrestling with Whiteness." One hundred people signed up for the first cohort, and another hundred signed up for the next session, which Fox said may be in part due to the national attention on anti-Black racism.

The series is for white leaders to have a more, "discerning relationship with our whiteness" according to Fox. The online series is adapted from curriculum from the Faith in Action Network, a Jesuit-founded, multi-faith community organizing network.

The question of whiteness in religious settings is a topic Rev. Anne Dunlap, a United Church of Christ minister who serves as national faith program coordinator at SURJ, works to incorporate into SURJ's faith-organizing work. Dunlap works with leaders from all faiths, including Catholics like Chenault in Louisville.

"We've had an explosion of folks coming in," Dunlap said.

Advertisement

Prior to the unrest following this summer's police killings, SURJ had approximately 130 chapters around the U.S. and one in Canada, but now Dunlap says there are too many new chapters to count. SURJ chapters are generally geographically based but many have ties to churches as well.

"The role of the faith work is to really resource white folks of faith who find themselves in our network, and to bring more white folks of faith."

SURJ chapters work locally with Black Lives Matter chapters and other groups, and play a supporting role in initiatives originating within BIPOC communities.

"For example, right now where we are seeing the call for Black lives and to defund the police," Dunlap said. "We're resourcing chapters and communities on the ground to go to their city councils to work on the budget, and we're working on a toolkit for congregations to use to stop using police, as a church, as a synagogue, as a community."

Chenault noted that churches are a great place to begin organizing for justice.

"I think where there are places people are already in community, it is a natural place to organize and to activate," Chenault said.

Chenault added that religious communities offer the "meaning-making" relationships and deep spirituality needed in movement circles to maintain the work amid action-fatigue.

"Folks know we have to take care of not only our bodies, but our souls, to maintain the level of commitment we're asked to maintain now," Chenault said.

[Sophie Vodvarka is a freelance writer based in Chicago who covers travel, spirituality and current affairs. Follow her on Twitter: @SophieVodvarka.]