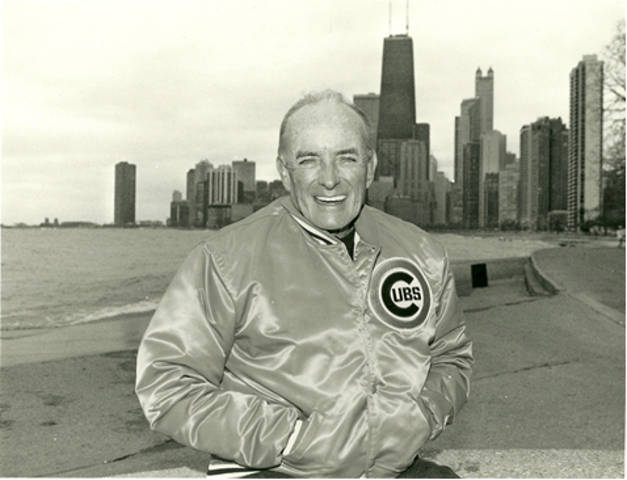

Fr. Andrew Greeley with the skyline of his hometown Chicago. (Photo from author's private collection.)

"I wouldn't say the world is my parish, but my readers are my parish. And especially the readers that write to me. They're my parish. And it's a responsibility that I enjoy."

-- Andrew Greeley

On Nov. 7, 2008, on a windy day in Rosemont, Ill., Fr. Andrew Greeley, wearing a Barack Obama baseball cap and a light raincoat, stepped out of a cab. His raincoat caught in the door, the cab pulled away, and Greeley fell to the ground, smashing his head. He suffered a fractured skull, and his brain would not stop bleeding. He was no longer able to write the novels that used to write him, initiate the witty repartee that delighted friends and confounded foes, or look at you with twinkly blue eyes that showed complete interest in what you were saying. Those eyes closed for good on May 30, 2013.

I am grateful to Andrew Greeley, one of the most creative Catholic thinkers of our time, for 50 years of kindnesses. When I was 20 at St. Mary of the Lake Seminary, I received a handwritten letter from the 33-year-old priest, praising a short story I had written in the seminary's literary magazine, The New Southwell. Fr. Greeley was already a famous priest with two important books under his belt, The Church and the Suburbs and Strangers in the House: Catholic Youth in America. He not only encouraged me to continue writing, but recommended the story to the editor of the popular Catholic magazine The Critic. The story wasn't published because a seminarian couldn't get anything published outside the seminary without the permission of the rector who never gave permission, Catch-22. But Fr. Greeley's kindness to me, someone he didn't even know, thrilled me, and was an example I would follow years later in my publishing career.

When I was 28 and had decided to leave the priesthood and move a thousand miles away to New York City, with no money and no job, and marry a girl I had known for four days in person and three months by phone, I went to see (now) Andy for advice. He lived in a small basement room at St. Ambrose Parish on Chicago's South Side. You entered by a side door and had to navigate towers of books that looked like the Chicago skyline. I sat in a chair across from him, and told him the whole story.

"So, the thing is," I said, "I don't know if it's going to work out but my whole being is telling me this is what I have to do. If it was an actual voice, there'd be an earthquake. I was wondering if you would do me a gigantic favor and write some of your editors and see if maybe I could get a job interview. I have to work for money now and I thought I might be good at being a book editor. I love books. What do you think?"

Andy looked at me a long time, his chin resting on his fingers, then said, "I'll help you find a good psychiatrist."

We talked all night.

He wrote letters to the editors of Doubleday, Macmillan, and Sheed & Ward.

They all interviewed me. None of them gave me a job because I had no experience.

But Andy believed in me, and Vickie loved me, so I knocked on every door.

Just before my money ran out, a kind man at the Seabury Press hired me to write educational publications for the Episcopal church. I was grateful for the job, but I wanted to be a book editor. I soon realized the only way that was going to happen was if I acquired books without being asked, in addition to the job I had, and present the proposals to the publisher. I first proposed a book called The Sexual Celibate by a Dominican named Donald Goergen, based on an article he had written for an obscure theology journal. Everybody thought I was nuts. "There's a sexual revolution going on. Nobody's going to buy this." They gave in, and the book was a best-seller. So the boss let me be a book editor as long as I would also direct the department I was already in. No problem. I did both jobs so I could I could "make my bones" at the one I loved. I called Andy and asked him to write a book on the prayer of St. Patrick, May the Wind Be at Your Back, for a series I wanted to start on classic prayers. He said yes. He always said yes. The series got off to a fantastic start, and so did I.

We did many books together, some that I suggested and some he just sent me, and they were among the best books I would ever publish. The Mary Myth championed the feminine aspects of God. Neighborhood sang a hymn to the value of community and presaged a future president. The Communal Catholic predicted what Catholics would be like in the future and the prediction came true. The Great Mysteries was the first out-of-the-box catechism, is still in print and taught after 40 years.

Andy's books, his seminal articles, his work as a sociologist of religion, and his constructive criticism of the church made him a popular guest on talk shows. I remember when he was the sole guest on "The Phil Donahue Show." A woman in the audience asked him, "If you're so critical of the church, why don't you just leave?" He famously said, "I like being Catholic!"

I asked him to write a book called I Like Being Catholic. He wanted to but was too busy. I asked again the next year. He said wait. I asked again in a year. Andy said, "Look, you should write it." So I did. It was the most successful book I ever did.

In the 1970s, Greeley the author entered a new orbit. It was as if the big black obelisk from "2001: A Space Odyssey" appeared in his study and turned him into a new creation. He called and said, "Mike, I'm going to write novels now. I can reach more people that way. I want to tell stories of God's love. I know Seabury doesn't do fiction, but I was thinking you might help me on your own time and be my editor. I make a good salary from the University of Chicago and will pay you what you need. What do you say?"

I said, "Send me whatever you've got and I will edit it for free. I'm writing my own book at night so just give me time." He sent me two manuscripts: a literary novel called Death in April and a science fiction novel whose name I forget but the hero manned a spaceship called "The Mayor Daley" and I liked that. I left the first novel to the side and had fun with the second. The science fiction novel didn't get published. McGraw-Hill published Death in April, but few people read it. Andy honed his skills on his own and found an agent. His next novel was The Cardinal Sins, read by millions of people around the world. A popular Catholic novelist was born.

Andy received criticism because his novels had mild sex scenes and some people couldn't tolerate that a priest might know and write about such things. To him, sex was a sacramental sign of God's incredible love for us. Everything was a sacrament to him! He could see a movie and find five Christ figures in it, even if the movie was "Gidget Goes to Rome." He was totally sincere about seeing God's love "lurking around corners." And he not only knew that "the chosen part" of sex between spouses was unselfish love but that unselfish love made for the best sex. A man doesn't have to have sex to know that this is so, or to celebrate it. Andy loved celebrating the good stuff.

Most of all he loved writing novels. "The storyteller is like God," he said. "The storyteller creates these characters. Falls in love with them, and then they won't act right." One of his lasting contributions is to show us that God is a Storyteller who writes straight the crooked lines of our lives, and that Catholicism is all about the stories. He observed, "Religion has been passed down through the years by stories people tell around the campfire. Stories about God, stories about love. Practically speaking, your religion is the story you tell about your life."

In the 1980s, I was president of the Crossroad/Continuum publishing company and got another phone call. "Mike, I've been writing a journal for a number of years and, I don't know, I think there might be some spiritual stuff in there people might find helpful. Would you mind taking a look and see if you think anything's worth publishing?"

Three days later a box with hundreds of pages covering Andy's life and intimate thoughts over the past three years arrived like a package from a Unabomber intent on blowing himself up. It was extraordinary. It revealed a sensitive man who often suffered depression and did care what people thought about him, despite his public poses to the contrary. It revealed a man who most of all wanted to love God and let people know that God was a Tremendous Lover who loved them as if he loved them alone and loved everyone as if all of them were one. I looked at the massive manuscript the same way Michelangelo looked at a block of marble: "It's not a block of marble. There's a lion in there!"

Andy did write about the spiritual life in his journals but also talked about his joys and his conflicts and he named names. It was no secret that he thought most American bishops were "morally and spiritually bankrupt" — he wrote about it in newspapers — and he told some juicy stories here, but I saw my main job as an editor was to protect Andy from himself. So I spent two full weekends carving the marble down to what would be a small personal book called Love Affair: A Prayer Journal. It won a Catholic Press Association book award in the spirituality category, and every couple of years I would do it again. These prayer journals were among his favorite books. I think most if not all of them are out of print now, but I'm grateful that I was able to work on them for him, his family and friends, and loyal readers.

His family and friends knew that while Andy could show a dark side like everyone else, he was one of the kindest and most generous men you could ever know. Some priests knocked him because he earned lots of money and lived well. But they never praised him when he gave a million dollars to St. Mary of the Lake Seminary or to the University of Chicago, or he tried to give a million dollars to the archdiocese to support inner-city schools rather than close them and Cardinal Joseph Bernardin refused his gift. Greeley would establish a private fund for the schools, and later endowed a scholarship fund. I know one reason he kept on writing novels even when sales inevitably began to slip was not to live well but to keep on supporting others.

The other Andrew Greeley I will always remember is the one who hated war, and wrote with fierce passion on the Iraq War. Andy had the clarity and rigor of an Old Testament prophet and I felt these writings deserved to be made public. In 2007, I asked his assistant, Roberta Wilk, to compile his essays from the Chicago Sun Times, and I published A Stupid, Unjust, Criminal War: Iraq 2001-2007. It was Andy's title, not mine, and while some of my colleagues thought the title was too harsh, I insisted it stay (one of few times I've ever done that) rather than wait for a consensus. Reviewers perceived the book as the most comprehensive and incisive Catholic view of the Iraq War we would ever get. Historian Garry Wills wrote, "Andrew Greeley shows that Jesus is the Prince of Peace, not a Captain of War."

Dan Herr, the great Chicago publisher, once said, "I used to think there were four Greeleys. I was wrong. There are more than that."

I will always remember just one: the priest who encouraged me 50 years ago and whose kindnesses never stopped.

[Michael Leach, formerly president of the Crossroad/Continuum Publishing Corporation and publisher of Orbis Books, received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Catholic Book Publishers Association in 2007.]