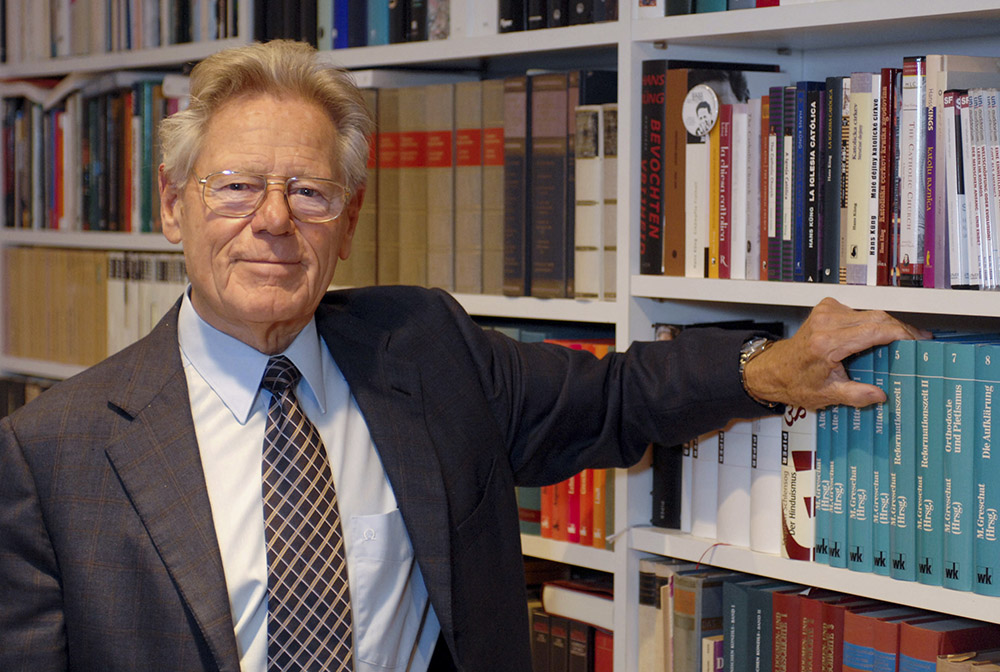

Theologian Fr. Hans Küng is pictured in his office in Tübingen, Germany, in February 2008. (CNS/KNA/Harald Oppitz)

Catholic priest and theologian Hans Küng, the renowned scholar and prolific writer who had lived with Parkinson's disease, macular degeneration and arthritis since 2013, died April 6 at his home in Tubingen, Germany. He was 93.

Few men throughout Christendom have had as much to say or had their work seen by as many Christians — and others — as Küng, the celebrated and controversial Swiss theologian and Catholic priest.

Open a magazine or turn on the television in Europe and it's likely the viewer caught the face and heard the Germanic-toned voice of the famous Swiss professor who lived, taught and lectured more than 40 years in Germany. Often, he was photographed in the company of heads of state — Britain's Tony Blair, the Soviet Union's Mikhail Gorbachev, Germany's Helmut Schmidt, as well as world religious leaders.

He frequently carried on public dialogues with scholarly representatives of Buddhism, Chinese religions, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism. He also met with U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan as he pursued his quest for a global ethic as a pathway toward international peace in the 21st century.

Tens of thousands of his readers living beyond Europe's borders in America, Australia, Asia and Africa had heard him too, or at least read one or more of his tomes. He was the premier Catholic theologian to speak in China on religion and science, the first theologian to address a group of astrophysicists, and later the European Congress of Radiology on the subject of a more humane medicine.

Reasons for his popularity were ubiquitous: readability, clarity, erudition, honesty, fearlessness. He was smart, occasionally profound. Someone less intellectually gifted could understand his arguments and be drawn to his texts and his talks for just that reason. He said and wrote what he thought needed to be aired in what he deemed his relentless struggle for intellectual freedom and his passionate search for truth.

Fr. Hans Küng in 1974 (CNS/KNA/ Hans Knapp)

In his most popular book — Christ sein (On Being a Christian) — which quickly sold more than 200,000 hard covers in German alone when it was released in 1974, Küng said he probed theological issues that are of concern to any educated person. He wrote for those "who believe, but feel insecure," those who used to believe "but are not satisfied with their unbelief" and those outside the church who are unwilling to approach "the fundamental questions of human existence with mere feelings, personal prejudices and apparently plausible explanations."

For such a wide audience, Küng kept the Scriptures and the daily paper close at hand. From age 10 when the Nazis invaded Switzerland's neighbor Austria, thus initiating World War II, the lad Hans — eldest of seven Küng children — began reading the daily paper. It was a discipline he maintained to his death despite declining vision. Keeping up on world and religious affairs rendered him "a realist, not a romanticist," he told this reporter at a number of our meetings.

Often controversial, the name "Küng" came with its own brand of adjectives in conservative church and political publications: He was Küng the dissident, the bête noire, the disobedient, the heretic, the apostate, the errant, the Protestant. In short, "l'enfant terrible of the Catholic Church," yelled many a headline.

His 1971 book, Infallible?: An Inquiry, caused an uproar across the Catholic world, challenging the papal infallibility declaration promulgated in 1870 at the First Vatican Council. Küng probed its theological basis and found the claim of supreme papal authority to be an impasse to reunion with other Christian churches.

The book appeared only three years after the Vatican had asked Küng to answer charges brought against his earlier volume, The Church. Catholic officials disputed the theologian's understanding of papal authority and requested he appear in Rome to answer charges.

Küng stood his ground. He would not recant. He wanted to see the file the Vatican had amassed on him. He demanded a written list of the questions regarding his book as well as the names of those vetting the work. He asked to speak in German during any meetings with Vatican officials and further requested that the Vatican pay his travel expenses to Rome or else hold the hearings at Küng's house in Tübingen.

Besides taking on infallibility, Küng also criticized the law of celibacy, favoring instead a married clergy and a diaconate, with both open to women as well as men. He argued compulsory celibacy was the chief reason for the shortage of priests, and he accused the hierarchy of preferring to deny the faithful a close-to-home celebration of the Eucharist for the sake of maintaining mandatory celibacy. The law contradicted the Gospel and ancient Catholic tradition and ought to be abolished, he wrote.

He found fault with the ban on dispensations for priests who wanted to leave the priesthood — introduced by Pope John Paul II after his election as pontiff in 1978 — calling it a violation of human rights.

His historical critical approach to research led him to conclude that the early Christian communities in Corinth and elsewhere had had lay members preside over eucharistic services in the absence of a priest.

He took issue with the church's ban on artificial contraception and its inhibitions in matters of human sexuality. He even had the chutzpah to critique the first year of the pontificate of John Paul II. In an essay appearing in eight papers across Europe, the Americas and Australia, Küng questioned whether the new pope was open to the world, was a spiritual leader, a true pastor, a collegial fellow bishop, an ecumenical mediator or even a real Christian.

Küng acknowledged that traditional Catholics would find the putting of such questions to the popular pope "more unforgivable than blasphemy." But he said his criticism arose from "loyal commitment" to the church and he felt "the pope has a right to a response from his own church in critical solidarity."

License to teach revoked

Headline writers and broadcasters had their day Dec. 18, 1979, when the Vatican pulled the rug out from under Küng's teaching career, revoking his missio canonica, or license to teach as a Catholic theologian at the University of Tübingen, where he had been since 1960. Such a license is required to teach as a Catholic theologian at a pontifically recognized institution, like Tübingen's Catholic theology school.

Advertisement

The German secular university has long had separate schools of Catholic and Protestant theology. Its Catholic school, at which Küng served as professor of dogmatic theology from 1963 to 1979, is renowned for its modern interpretation of the New Testament.

In Disputed Truth, Book 2 of his three volumes of memoirs, Küng spent 80 pages reviewing charges against him — secret meetings by German bishops and Vatican officials outside of Germany, betrayal by seven of his 11 Tübingen colleagues and a near physical and emotional breakdown caused by exhaustion from his efforts to answer Vatican accusations while preserving his place in a state university.

In the end, Küng retained his professorship, not in the Catholic faculty, but in the university's secular Institute for Ecumenical Research, which he had founded and directed since the early 1960s. He also remained "a priest in good standing," which upset those who sought his excommunication. Despite his outspokenness, Rome recognized his lifelong devotion to the church and allowed Küng to preach and to publish until illness and disability slowed him in 2013.

Küng indicated a certain dismay in 1979 when he learned of the involvement of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in the removal of his teaching license. As dean of theology at Tübingen in the early 1960s, Küng had offered — and Ratzinger accepted — a professorship at Tübingen. But following student revolts in Germany in 1968, Ratzinger left academia, returning to his native Munich where he became archbishop, then cardinal. He later headed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for 25 years under John Paul.

Fr. Hans Küng at home in Tübingen, Germany, in 2010 (Newscom/JDD/SIPA/Eric Dessonsk)

To the surprise of many, Küng requested a meeting with Ratzinger shortly after Ratzinger was elected pope in April 2005. The two priests had retained their respect for one another and a limited correspondence over 45 years. Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, quickly agreed to meet Küng. The pair talked for four hours and dined at Benedict's summer residence at Castel Gandolfo.

A communiqué issued by the Vatican two days after the Sept. 24, 2005, reunion indicated the meeting was friendly and that Benedict praised Küng for his efforts to build a global code of ethics that enshrined the values that were held in common among religions and recognized by secular leaders, too.

The two did not take up any doctrinal questions. Nor did Küng ask that his teaching license be restored. Instead, they found accord on matters relating to science and religion, faith and reason, and social issues concerned with ethics and peace-building.

Although their shared evening was but a scintilla of time compared to the quarter-century that Küng had been in a state of strained relations with the Vatican, the theologian saw it as a sign of openness and even a harbinger of hope for those who share his critical vision of the church and what he had oft termed its "inquisitional proceedings" against him and against other dissidents.

For years, Küng had asked priests and bishops to show some courage against what he called a repressive Roman system that demanded obedience over reason and conformity over freedom of conscience. What was it in fact that gave this renegade thinker such abiding confidence in the midst of decades of struggle?

A hint is provided in On Being a Christian, which has seen many editions and been translated into dozens of languages. Küng called it "a small Summa" on which he worked for seven years. Its 720 pages probe whether Christian faith could continue to meet the challenges of the modern world and whether the Christian message was an adequate one for today's men and women. Küng said he wrote it because he did not know what was specifically Christian, and he needed to find out.

'I have an infinite intellectual curiosity. I am never satisfied. I must always know more about everything so I can detect just what are the problems. I do not have many prejudices before starting, as I do not fear the outcome.'

—Hans Küng

Early in the work, Küng quoted German physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, who said: "There is one thing I would like to tell the theologians: something which they know and others should know. They hold the sole truth which goes deeper than the truth of science, on which the atomic age rests. They hold a knowledge of the nature of man that is more deeply rooted than the rationality of modern times. The moment always comes inevitably when our planning breaks down and we ask and will ask about the truth."

Truth-seeking was the chosen task to which Küng brought his insatiable probing and unquenchable intellect.

"I have an infinite intellectual curiosity," he told this reporter during the first of many meetings over nearly 40 years. "I am never satisfied. I must always know more about everything so I can detect just what are the problems. I do not have many prejudices before starting, as I do not fear the outcome.

"Christology presents so many problems and so people say: 'It's dangerous to touch the virgin birth, the pre-existence of Christ, the Trinity.' But I think the truth cannot do harm — not to me personally and not to the church," he told NCR.

The chance to reflect on God gave Küng enormous pleasure and satisfaction, he related in My Struggle for Freedom, the first volume of his memoirs.

'I can swim'

Already as a youngster, Küng recalled coming home "radiant" when he realized "I can swim ... the water's supporting me." For him, this experience illustrated "the venture of faith, which cannot first be proved theoretically by a course on 'dry land' but simply has to be attempted: a quite rational venture, though the rationality only emerges in the act," he wrote in his first memoir.

A lifelong lover of nature, Küng spent much time in its environs — swimming almost every day of his life and skiing up to age 80 during brief holidays in Switzerland. Skiing helped him if only for a few hours to "air my brain and forget all scholarship, often defying the cold, wind, snow and storm," he attested in his memoir.

Almost all of his books were composed in longhand as Küng sat on his living-room-sized terrace in Tübingen, close to the banks of the Neckar River, or alongside his Lake Lucerne home in his native Sursee, Switzerland. Sunshine and fresh air pervade his texts as much as do research, history, exhaustive scholarship, and analysis of and solutions to specific theological and philosophical problems.

'The nicest liturgical words and the highest praise of Christ — unless backed by Scripture and understood by the people — are just not useful.'

—Hans Küng

The inclement elements to which Küng alluded while on the Alpine slopes became the stuff of weathering the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In fact, the Holy Office — as it was known in pre-Vatican II days — opened a secret file (the infamous 399/57i) on Küng shortly after he wrote his first book and doctoral dissertation, Justification, in 1957. In it, Küng predicted that an agreement in principle between Catholic theology as set down at the 16th-century Council of Trent and 20th-century Reformation theology as evidenced in Swiss Reformed* theologian Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics was possible.

Although only 28 when he published this conclusion, it would be the first of many ecumenical and interfaith inquiries that solidified his own roots in a living faith in Christ, which he said lasted his entire career and helped him always to be open to other faiths. Indeed, Küng long held that steadfastness in one's own faith and a capacity for dialogue with those of another belief are complementary virtues.

Four decades after writing Justification, Küng brought out volumes on Christianity, Judaism, Islam and Chinese religions. In the course of his research, he met frequently with religious leaders in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Of these meetings, he said he initially had more questions of faith (dogmatics) than of ethics (morality). But in the course of time, it dawned on him that despite dogmatic differences between the religions, there were already decisive common features in ethics that could be the foundation for a global ethic.

So, at the start of the 1990s, Küng was well-prepared to take on the task of preparing a Declaration Toward a Global Ethic for the Parliament of the World Religions that convened in Chicago in 1993. The most referenced part of the declaration was no peace among the nations without peace among the religions.

Not surprisingly, the child who discovered he could swim became the man who recognized the three great river systems of the high religions of China, India and the Semitic Near East, which he found in preparing a journey of many weeks to sub-Saharan Africa in 1986 and while working on a German television series in Australia in 1998.

Fr. Hans Küng in 2015 (CNS/KNA/Harald Oppitz)

None of this would have happened had he not had his teaching license withdrawn in 1979, he later admitted.

Nor would it have occurred had he not been ordained a Catholic priest. That event took place in 1954 in Rome. Küng celebrated his first Mass in St. Peter's Basilica and preached to the Swiss Guard, some of whom he knew well after seven years studying philosophy and theology in Latin at Rome's Jesuit Gregorian University.

He completed a further three years of study in French for his doctorate at the Sorbonne and the Institut Catholique in Paris, where he wrote his Justification thesis.

Küng returned to Switzerland, serving two years as an assistant priest in Lucerne. Barth invited him to lecture in Basel on the theme: The church always in need of reform. Some in the audience found his enthusiasm for renewal over-optimistic. However, on Jan. 25, 1959 — the week following his talk — Pope John XXIII called for a Second Vatican Council. And Küng in preparing his reform lecture of Jan. 19 had already amassed extensive notes for a volume on just such a venture.

That book, The Council, Reform and Reunion, became programmatic to a number of Vatican II documents, including those on scriptural study, worship, liturgy in the vernacular, on dialogue with other cultures and faiths, on reform of the papacy, religious liberty and on the abolition of the Index of Prohibited Books.

Vatican watcher and former NCR Rome correspondent Peter Hebblethwaite ventured that no theologian would ever again exert as much influence on the agenda of a council as Küng had. Not only was The Council, Reform and Reunion a best-seller in Germany, Holland, France and the English-speaking world, it bore the approval of Vienna's Cardinal Franz König, who dictated its imprimatur to Küng from his hospital bed after sustaining grave injuries in a road accident.

Council adviser

Shortly after the book's release, Küng's bishop, Carl Joseph Leiprecht of Rottenburg, Germany, invited him to be his personal peritus, or expert, at the upcoming council. Küng was hardly keen about a return to Rome. But a number of colleagues persuaded him that the council promised to be the church event of the century and Küng dare not miss it.

"How am I to suspect that this yes will determine my fate for almost a decade and beyond?" he noted in his memoir.

At 34, Küng was the youngest expert at the council, soon joined by Dominicans Edward Schillebeeckx of Belgium and Yves Congar of France; German priests Ratzinger and Karl Rahner, plus U.S. clerics John Courtney Murray, George Higgins, John Quinn, Gustave Weigel and Vincent Yzermans.

A younger Fr. Hans Küng is seen in an undated photo. (Newscom/Album/sfgp)

Not only did progressive bishops seek out Küng's acumen and writing skills, but his fluency in French, Italian, Dutch, German, English and Latin made him the go-to guy in dealing with the press. He was quick to publish his views on council texts and backroom maneuvering in leading papers and was a frequent television guest, remembered as much for his good looks and business suits as for his expertise.

During the council's third session in October 1964 — by which time Pope Paul VI had replaced the late John XXIII — it looked as if the new pontiff was about to postpone a vote on key declarations on religious liberty and on the Jews by first returning them for further checking to the highly conservative Curia.

Working behind the scenes but at the behest of powerful progressive churchmen, Küng helped convene meetings with 13 cardinals who quickly drafted a protest letter to the pope. Before the ink had dried, Küng breached the secrecy imposed on periti and put the public in the picture. He telephoned reporters at top European newspapers and briefed them "on the scandalous machinations" against the two declarations.

When the bishops returned for their session on Monday morning, they were greeted by a storm in the international press. The uproar plus the personal intervention by cardinals with the pope meant that both schemata remained on the council agenda. The draft on the Jews passed 1,770 to 185 on Nov. 20, 1964.

A year later, the bishops voted in favor of the Declaration on Religious Liberty 2,308 to 70.

On Dec. 2, 1965, Paul VI invited Küng to a private audience. It lasted 45 minutes — more than twice as long as predicted. Küng recalled the pontiff's telling him that having looked over everything Küng had written, the pope would have preferred that he wrote "nothing." This was after the pontiff had lauded him for "his great gifts" and suggested Küng use his talents at the service of the church.

Conform

Confused but still smiling, the theologian assured his supreme boss, "I'm already at the service of the church."

To this, the pope implied Küng must "conform" if he really intended to serve the church. Before leaving the papal library, Küng managed to steer the conversation to the disputed issue of contraception, offering the pope a memorandum with a dozen points for him to hand on to his papal commission studying the birth control issue.

'My theology obviously isn't for the pope [I will do theology] for my fellow human beings … for those people who may need my theology.'

—Hans Küng

He later recalled that the audience with Paul VI confronted him vividly with the question: For whom was he doing theology? Already in late 1965, Küng understood: "My theology obviously isn't for the pope (and his followers), who clearly doesn't want my theology as it is."

On that very day Küng resolved he would do theology "for my fellow human beings ... for those people who may need my theology."

Over the years following the council, Küng would point out frequently the hundreds of letters he received and the comments from crowds of supporters who attended his lectures in Germany and abroad testifying that they remained in the church because of his vision, his theology and writings.

His spring 1963 lectures in the United States, following the first session of Vatican II, drew more than 25,000 people to Notre Dame, Boston College and Georgetown University and to venues in California, Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. At St. Louis University, he received the first of many honorary degrees, but the Jesuit school was chastised for not first seeking Rome's permission to honor Küng.

On April 30, 1963, President John Kennedy welcomed Küng to the White House, introducing him to Vice President Lyndon Johnson and congressional leaders with the words: "And this is what I would call a new frontier man of the Catholic Church."

In November 1983, on the 20th anniversary of Kennedy's assassination, Küng shared with this reporter how privileged he had felt to live during "the reign of the two Johns."

Noting that John XXIII's death had come only five months ahead of Kennedy's, Küng recalled that each man's time in office was cut short. Yet each had a brief window of opportunity that they seized — the pope in calling the council, the president in working on arms control with the Soviets, Küng said while relaxing in his hotel room in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he was teaching the autumn semester at the University of Michigan.

On visits to his home in Tübingen in 1977 and 1985 and during subsequent meetings in Berkeley, California; New York; Ann Arbor; Detroit; Chicago; Pittsburgh; and Mahwah, New Jersey, this reporter held wide-ranging conversations with Küng about his faith, his family, the role of God, prayer and liturgy in his life.

'I have a real aversion to bad liturgy. I think it is essential that people feel immediately that the man presiding believes what he says, is committed to this cause, is addressing them and not just performing prayers.'

—Hans Küng

Those privileged to see Küng say Mass — as this reporter was in Greenwich Village where he preached on the Sonship of God in the late 1980s — saw a man of deep faith who gave as much attention to the words and symbols of the liturgy as he did to composing his books and lectures.

For years, he had presided at the 11 a.m. Sunday Mass at St. Johannes Kirche (St. John's Church) in the center of the Tübingen campus. Küng had proposed the Mass for professors.

"I have a real aversion to bad liturgy," he said. "I think it is essential that people feel immediately that the man presiding believes what he says, is committed to this cause, is addressing them and not just performing prayers. The nicest liturgical words and the highest praise of Christ — unless backed by Scripture and understood by the people — are just not useful," he said in Tübingen.

Years later in a final seminar on "Eternal Life" delivered to 20 students and 20 auditing professors at the University of Michigan, Küng focused on the Last Supper.

"We see a man facing his death. It's very simple. It's a ceremony in a traditional Jewish context. He takes bread, gives his blessing, breaks it, passes it out," Küng said, extending his arms to those close to him. "He knows it's his last time with them. He says: 'Take. My body. Remember me. This night.' "

Students exchanged glances. Person to person. Catholics and Hindus. Moist eyes and silence. A sense of communion filled the seminar room.

"There are depths of piety in this man that we've not yet begun to fathom," biblical scholar David Noel Freedman told NCR after the seminar. Freedman credited Küng's strong faith to his very traditional Swiss Catholic upbringing, his strong mother, and his father who ran a shoe store in the middle of Sursee — "and those five sisters of his."

*This article has been edited to correct Karl Barth's denomination.