Pope Francis prays at the south fountain at the ground zero 9/11 Memorial Sept. 25, 2015, in New York. The pope is accompanied by Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York. (CNS/Paul Haring)

When terrorists wreaked havoc on the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, it forever altered global affairs — including, inadvertently, paving the way for a relatively unknown Argentine cardinal to eventually become pope.

Twenty years ago after the tragic events of 9/11, Cardinal Edward Egan had the task of tending to a grieving city and flock in New York City, the epicenter of the attacks. He had also been charged with serving as the general rapporteur (or relator general) of the 2001 Synod of Bishops in Rome set to begin on Sept. 30. In that capacity, he was to be responsible for outlining the themes of the synod, organizing and liasoning with the synod fathers and summarizing the synod discussions before the final proposals are reviewed by the pope.

Then-Cardinal-designate Edward M. Egan celebrates Mass Jan. 21, 2001, at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York. He said that being named a cardinal was an honor ''first and foremost for the Archdiocese of New York.'' (CNS photo/Catholic New York/ Maria Bastone)

Joseph Zwilling, spokesman for the archdiocese of New York, told NCR that Egan requested from Pope John Paul II, through then Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Angelo Sodano, that he be permitted to give the opening report at the synod and then be allowed to return to New York.

"As Cardinal Sodano relayed it to Cardinal Egan, the Holy Father requested that he stay, which he did, reluctantly but obediently," Zwilling recalled.

But a mourning city drew Egan back home, and halfway through the monthlong synod he received permission to return to New York for a prayer service for victims of Sept. 11, eventually returning to Rome for a short stay before finally being granted a dispensation to return to the states for good.

Enter Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the then-cardinal archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, who was the synod's adjunct rapporteur, serving as Egan's number two.

During the monthlong gathering of bishops from around the world, as Egan's home diocese kept his focus elsewhere, the Argentine cardinal took on greater responsibilities, both publicly and privately, getting him noticed around the Vatican and beyond.

"Bergoglio's role in that synod of 2001 was very important and crucial for his later election. In fact, he worked so well as relator, replacing Egan, that he started being known and noticed in Rome as someone papabile,'' meaning likely to be a contender for the next pope, said Argentine journalist Elisabetta Piqué.

"From then on he remained on the radar of many cardinals — not just progressives — looking for a successor of John Paul II," she told NCR.

Shying away from the spotlight, shining when necessary

As Bergoglio took on the demands of his new role at the 2001 synod, journalists covering the gathering took notice, often commenting that while the Argentine cardinal shied away from the spotlight, he proved a capable communicator when it was needed.

Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, Argentina, is pictured in an undated file photo. (CNS/Catholic Press photo)

"Bergoglio excels in one-on-one communication, but he can also speak well in public when necessary," wrote veteran Vatican journalist Sandro Magister in L'espresso about Bergoglio's role in succeeding Egan at the synod. "Bergoglio managed the meeting so well that, at the time for electing the twelve members of the secretary´s council, his brother bishops chose him with the highest vote possible."

John Allen, covering the synod for NCR at the time, said "the votes are closely watched for indications of which prelates have impressed their peers," adding that "the results reinforced the reputations of these men as papabile."

Following the synod, Magister reported that Bergoglio's name was floated as a possibility to head an important Vatican dicastery.

"'Please, I would die in the Curia,'" he [Bergoglio] implored," wrote Magister.

"Since that time, the thought of having him return to Rome as the successor of Peter has begun to spread with growing intensity," Magister continued. "The Latin-American cardinals are increasingly focused upon him, as is Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger."

Piqué, the Argentine journalist, who is author of Pope Francis: Life and Revolution, told NCR the Synod participants were impressed by his ability to synthesize and express the views of the bishops, "and that's why in the 2005 conclave, he emerged as the real challenger to Benedict."

Four years later, following Pope John Paul II's death in 2005, Bergoglio was widely understood to be the runner-up to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who was elected as Pope Benedict XVI.

Yet as history has shown, Bergoglio had not been forgotten.

"In that sense," Piqué observed, "It's interesting to think what would have happened in the story of the church if 9/11 wouldn't have happened."

Synods and synodality take center stage

In many respects, the themes of the 2001 synod, which focused on "The Bishop: Servant of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for the Hope of the World," foreshadowed many of the same touchstones and tensions of the Francis papacy.

Papal biographer and collaborator Austen Ivereigh told NCR that, historically, a persistent "sticky issue" of synods has been the question "of the authority of the college of bishops itself, and its role in the universal governance of the church" and navigating "the right balance of collegiality versus primacy."

"The 2001 synod was a key moment in surfacing this call to collegiality, because there was a sense the John Paul era was at an end and that centralist governance had become a major obstacle to the church's mission," said Ivereigh.

Pope John Paul II embraces Argentine Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio after presenting the new cardinal with a red beretta at the Vatican Feb. 21, 2001, setting the stage for the Bergoglio's later election as Pope Francis. (CNS/Reuters)

He pointed to the 2001 consistory — when Pope John Paul II created a number of cardinals, including Bergoglio, from Latin America — as a tipping point.

"Because that consistory was made up of so many Latin American cardinals, there was a sense that the Catholic heartlands — Europe and Latin America — were pushing for collegiality that was being resisted by Rome," said Ivereigh. "Bergoglio saw all this, and took note."

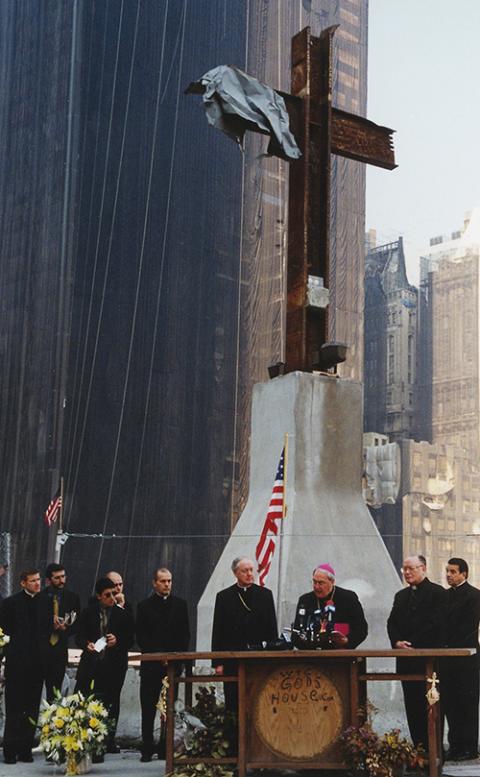

Archbishop Leonardo Sandri (at podium), a top official of the Vatican's Secretariat of State, says a prayer at ground zero in New York while laying a wreath at the site June 20, 2002. He was accompanied by Cardinal Edward Egan of New York (center left) and the permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, Archbishop Renato Martino (right). (CNS/Chris Sheridan)

During the 2001 synod, the issue emerged again, with one in five speeches among the synod fathers raising collegiality, according to Ivereigh. By contrast, collegiality was only mentioned twice in the synod's working document and Cardinal Jan Pieter Schotte had it excised from the final report.

"At his first press conference as relator following Egan's return to New York, Bergoglio was asked about collegiality," Ivereigh recalled. "Sitting next to Schotte, he said a proper discussion of this topic 'exceeds the specific limits of this synod' and needed to be dealt with elsewhere and with adequate preparation."

"Looking back, he was clearly signaling that collegiality could only be introduced through a thorough reform of the synod itself, to make it an instrument of collegial governance and ecclesial discernment," he said.

Piqué offered a similar assessment, telling NCR that Bergoglio's experience at the 2001 synod was "essential also for him to understand better the need of real consultation, with discussions, in the church, because he saw that those kinds of meetings were already pre-fabricated."

"It was all already carefully managed by Rome," she added. "The bishops were not really free to discuss any subject and to express their opinions. They knew that if they expressed an opinion that Rome did not like, their future career would be blocked."

And after being elected pope, Francis himself has not minced words about what he learned in the synod process and his belief reform was needed.

"I was the rapporteur of the 2001 synod and there was a cardinal who told us what should be discussed and what should not," he told La Nacion in 2014. "That will not happen now."

A universal church

Since Catholics believe (or at least hope) that the work of the Holy Spirit guides the synodal process, it may not be exactly fair to describe synods as an audition, in which church leaders from around the world demonstrate their own talents, preferences and priorities.

Yet it's an undeniable part of the experience.

"Synods have always been a means for bishops to get a sense of the universal church, to think globally, against a much bigger canvas than their own diocese and country. They are also potent experiences of that mysterious Catholic thing, 'communion,' " said Ivereigh. "Synods bond bishops to each other, and to Rome, making them aware that they are members of a collegium tasked with governing the whole church with and under the pope."

"One might say that at synods many bishops grow up, and become leaders of the universal church," he added.

Advertisement

Looking back at the list of participants in the 2001 synod, one can get an early glimpse of the cast of characters who would take on defining roles in the Francis era and those responsible for bringing it about.

A number of the members of the so-called "Sankt Gallen group," an informal association of cardinals who would meet and strategize about the future of the papacy and the church, were among those participating in the 2001 synod, including Cardinals Godfried Danneels (Belgium), Walter Kasper (Germany), Carlo Maria Martini (Italy), Cormac Murphy-O'Connor (England) and José da Cruz Policarpo (Portugal).

In addition, the 2001 synod provided an occasion for Bergoglio to take note of other potential leaders, men who would who go on to make cardinals following his election as pope. Among them: Cardinals Charles Bo (Myanmar), Gregorio Rosa Chávez (El Salvador), Wilton Gregory (United States), Carlos Aguiar Retes (Mexico), and Joseph Tobin (United States).

Ivereigh noted that many of the cardinals who participated in the 2001 synod had been impressed with Bergoglio's leadership qualities, but in the 2005 conclave neither Bergoglio or the church was ready for him to become pope. That would begin to change at the 2007 meeting of the Latin American church at Aparecida, which "was the continental 'Pentecost' that showed that Latin America was now the 'source' for the universal church."

"By the 2013 conclave, the crisis of governance had reached the point where the cardinals were willing to embrace the need for a change in direction," he continued. "That's when the Europeans and Latin Americans who knew him suggested Bergoglio to the rest of the college of cardinals who had barely any knowledge of him."

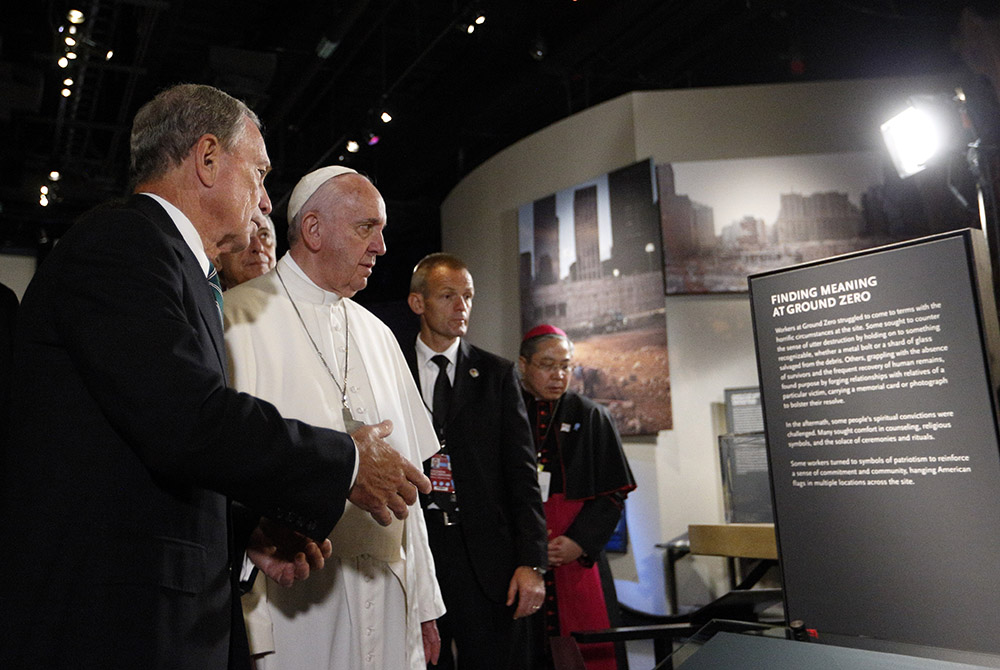

Pope Francis looks at an exhibit as he visits the ground zero 9/11 Memorial Museum Sept. 25, 2015, in New York. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Following Bergoglio's surprise election in March 2013, Egan — then retired — reflected back on the role that the then Argentine cardinal took on in 2001.

"He began working with us every day. He responded generously, kindly and very competently," Egan told Catholic New York in 2013. "He was simply wonderful. I became a great admirer of his."

"He's as fine a bishop and priest as anyone could hope for," he added.

The New York cardinal went on to mention that a few days before the 2013 conclave that elected him as Pope Francis, Egan was able to see Bergoglio, where he reminded him of an invitation he had made to him in 2001, one in which he had accepted: to one day visit New York.

Although Egan died in March 2015, just months later, Bergoglio made good on that promise in September 2015, finally making his first visit to the United States, and specifically to New York, where — as pope — he prayed on the memorial grounds for the victims of the Sept. 11 attacks.